Lara (Year 8) gives a stirring argument as to why the study of Ancient History is relevant for us today.

Watch the video below:

Lara (Year 8) gives a stirring argument as to why the study of Ancient History is relevant for us today.

Watch the video below:

Isabelle (Year 9) looks at the potential of quantum computing, delivering an informative video and article outlining this fascinating innovation.

We need to know the potential of quantum computing, the powerful approach to computation that our world is moving into.

There are endless ways in which we can use quantum computing. The first is from a biological aspect. A mysterious aspect of this subject are enzymes and understanding these can help to produce medicines for various major diseases. However, we don’t know a lot about enzymes due to their incredibly complex structures. Normal computers are also unable to model such a complex structure, so we need a different solution: a quantum computer. Quantum computers could predict this structure, along with several other properties.

This is just one example, but quantum computers could resolve so many problems in healthcare and can be applied to several different industries such as finance, transportation, chemicals and cybersecurity. The promise is that quantum computers can solve problems which we have pondered for years in a matter of a few hours.

And yes, it will take years, perhaps decades for this to develop in a way where the value is significant enough for many businesses, however it is important to know how it would work and what it could solve. Then, businesses can truly use quantum computers to their full potential.

How does a quantum computer work?

It is hard for the ‘normal’ computers that we use daily to solve complex problems. But this quantum computer has to potential to be able to solve specific, very complex problems, fast. It won’t replace our ‘normal’ computers; it will improve research. But here are two differences that make these quantum computers so powerful:

1. Our ‘normal’ computers use binary numbers – bits. They are made up of two number (one and off): one and zero. But these quantum computers are designed to use ‘qubits’, which can also represent a combination of one and zero.

2. 2. Our ‘normal’ computer can manage one calculation and one input. But the quantum computers can manage more. This gives the quantum computers their speed – they will be able to process multiple calculations simultaneously, with several inputs.

So, let’s combine this: if we have ‘n’ qubits, then the quantum computer is able to process many at once. That is fast and powerful.

Classical computing has the skill to find one particular result. However, a quantum computer is able to bring it down to a small range, which is so much faster. Afterwards, we can then use a classical computer to find one particular result, but it would take much longer to only use classical computers. The idea is there, but there are challenges which stop us from developing this so far.

Obstacles

We describe something as volatile if something is unstable. Qubits are volatile. In the ‘normal’ computers today, we have a bit which is 1 or 0. It is important that this bit on a computer chip does not interfere with other bits on the same computer chip, and we have managed to do this. However, the quantum computers would need to develop a structure where the qubits can interact with each other, so that they can process several calculations and inputs at once.

What then makes these qubits so volatile is that we need to be able to control these interactions. We need to allow them to interact, while still ensuring that no inputs are changed or deleted, which would harm the accuracy. This is a technical difficulty.

So, what happens now? The idea of quantum computing has been around since 1980, but only at the end of 2019 was there proof that it was really possible.

Source: McKinsey Quarterly Feb 2020

Naomi, Year 8, discusses the reasons as to why people procrastinate.

Procrastination. I have always procrastinated, whether it has been small things in my life like tidying my room to larger things, like writing an essay. We would be given a week to write an essay and I’d tell myself every single night ‘you’re going to start this tonight and spread the workload out until the deadline’. This never happened. Instead, I ended up procrastinating by doing an activity that I really didn’t want to, for example tidying my room or organising my books. I was always perplexed by the non-procrastinators in my life who would do their work when it was set.

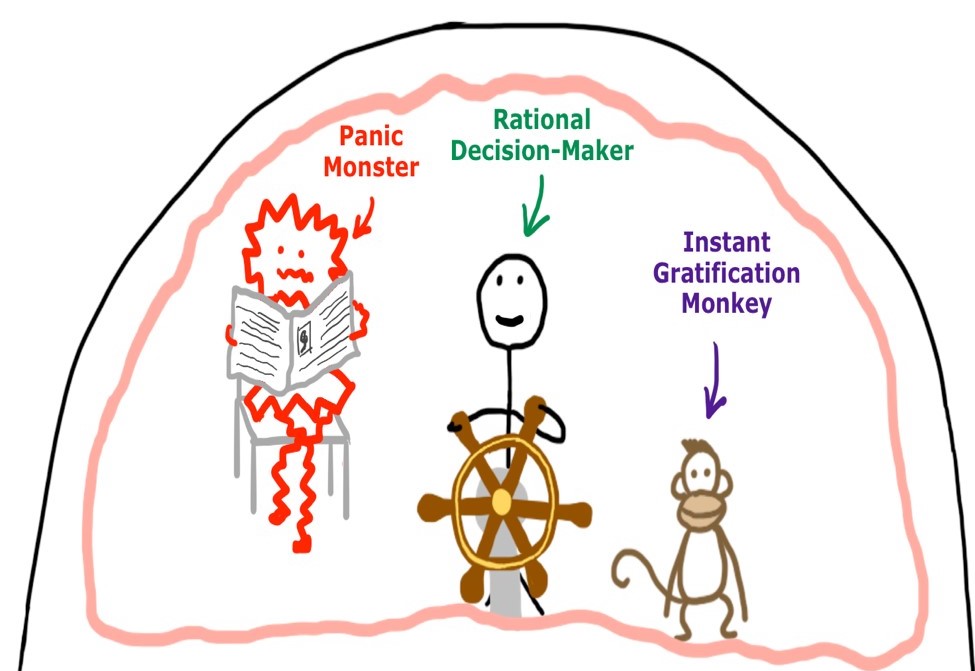

I was confused to the point where my dad, realising I could use some help, showed me a TedTalk by Tim Urban (linked below). It discusses the basic premise that in everyone’s mind there is a rational decision maker who encourages work to be done. However, there is also a voice in your head, the instant gratification monkey, which has no memory of the past and no regard for the future. It only cares about two things: ease and fun. When you have work to do the rational decision maker will make the rational decision to be productive, but the other voice in one’s head discourages this, so instead this voice takes control and we end up doing potentially meaningless (but fun) activities.

The instant gratification monkey is the animal instinct part of your brain, the amygdala. But because we humans are more advanced than other species, we also have the rational decision maker, in the prefrontal lobe, who gives us the ability to visualise the future, see the big picture and make long term plans. It makes the decisions to do what makes sense right now. When it makes sense to do things that are fun or easy, the two parts of your brain agree but when it’s time to do harder things, there is a conflict. In the mind of a procrastinator, the monkey wins every time, so we end up doing fun, pointless things.

So, the question still stands, how does a procrastinator ever get anything done at all if the monkey is always in charge. There is a simple answer to this question: there is another character in your brain called the panic monster, similar to the fight or flight instinct. The panic monster comes out whenever there is a scary or stressful consequence looming. When it comes out, the monkey goes away and we are scared into doing the work.

This works short term: we meet the deadlines. However, in the long term, it can cause anxiety and stress problems that will only get worse. The knowing that there is always something you should be doing cause continual stress which can become overwhelming and take over your life. Procrastination is an issue that many people suffer from. These three characters only work when there is a deadline and there are things in your life that don’t have deadlines that we want to do. After many years of suffering (dramatic, I know) I have only one solution: start.

Sources:

https://waitbutwhy.com/2013/10/why-procrastinators-procrastinate.html

Eleni in Year 12 discusses the benefits of being involved in drama productions, and gives some advice to anyone considering getting involved in future projects.

Whether you are well versed in appearing on stage or a newcomer to the dramatic arts, the WHS Drama Department fosters a welcoming approach towards all those interested in theatre. More often than not, pupils involved in productions will experience a distinctive emotional investment with regards to the piece they are rehearsing for. It is the gradual accumulation of this sense that allows the productions to become an effective release from the strenuous moments of the academic atmosphere, whilst also elevating its calibre as a creative output.

Whilst the number and types of productions vary year upon year, there are several that take place annually. These include:

Here are some top tips on auditioning from the drama staff:

The productions are an excellent platform to further nourish inter-year bonds. Encouraging different year groups to work together is something which the performing arts value, and can be seen in any inter-year production, with the cast being able to unite in an efficient and enjoyable team. The inevitability of inter-year friendships forming as a result to the productions, is one of the several enriching benefits that accompany the productions.

Having trained in Piano and Voice from a very young age, I was mostly involved in the music side of the school. However, my role as an onlooker changed to that of a performer in the Year 9 and 10 production of Little Shop of Horrors, where I was lucky enough to have been cast as Mr Mushnik. This opportunity inspired a huge passion for performing in me for both vocal and theatrical appearances. The following year, I was part of the senior production of Sweeney Todd, where I played the part of Johanna.

Having trained in Piano and Voice from a very young age, I was mostly involved in the music side of the school. However, my role as an onlooker changed to that of a performer in the Year 9 and 10 production of Little Shop of Horrors, where I was lucky enough to have been cast as Mr Mushnik. This opportunity inspired a huge passion for performing in me for both vocal and theatrical appearances. The following year, I was part of the senior production of Sweeney Todd, where I played the part of Johanna.

This stands as a great example of the performance potential for musicals with more classically oriented vocal writing. This year, I was fortunate to have played Tobias in Education Education Education which was also the first instance of my involvement in a school play (rather than the musical). With the aid of the drama department, I was able to develop my performance skills in an extensive variety of genres. It is safe to say that my involvement in drama at WHS has allowed me to approach theatrical opportunities in a more nuanced, informed and experienced manner.

Lizzie, Year 12, writes about what it is like being a music scholar preparing for the large WHS concert at Cadogan Hall later this month.

As the annual Cadogan Hall concert draws nearer, everyone involved is working hard to rehearse the music and make final preparations for the day, striving to improve upon the standard of the previous year. This is especially true of music scholars, who play various vital roles within the music department.

All musicians have the important task of individually practising their parts and potentially asking peripatetic teachers for help with really challenging passages to ensure they can not only play the music, but engage with the effect each piece is trying to convey. It is crucial that each and every part in the orchestra and choirs are learnt individually if the ensemble is to sound brilliant together. It means that the rehearsals, which are more limited in time than private practise, can focus on developing cohesion and emotion in the music in order to make it really impressive.

As a music scholar, I also have the role of brass section leader which entails many different things. These range from encouraging other musicians within my section to practise their parts at home, helping to tune in rehearsals and performances, and making stylistic decisions about how our part should be played so that it can sound within the overall emotion.

Section leaders also go through all of the music themselves and note down difficult passages that their section struggles with in order to help highlight them to Mr Bristow, who directs the Orchestra. We then focus on perfecting these few passages in sectional rehearsals, where the orchestra is divided into smaller groups to provide more attention to each part. This is key in making sure that all of the music is ready for the performance, giving each and every pupil in the orchestra the confidence to play to the best of their abilities.

There are also other student-led preparations that must be made and are carried out by scholars such as putting together the programme. This year a meeting was held to re-evaluate the normal design of the programme and to put forward new ideas in the hope that the programme will be not only informative for the concert, but also become more valuable for the pupils as a souvenir of the performance. In addition, scholars are each given a piece to write a programme note for, which contextualises the music for the audience. This requires researching the composer, piece itself, when it was written and then collating the information a brief but interesting way.

Music scholars, especially those in older years, tend to be much better at controlling the nerves that come with performing than other performers due to having more experience performing, like at the scholars’ recitals each term. On concert day it is always really nice to see that everyone is sharing in the excitement and anticipation ahead of the performance, but also helping to make sure that no one is getting very worried or anxious.

One of my other favourite parts is the inter-year bonding within the music department, stemming from shared interests, which displayed and strengthened every year at Cadogan Hall. From the manic and cramped atmosphere in the changing rooms, to the sad realisation that when it is over the leaving year 13s have performed their last ever big Wimbledon High concert, it always feels like the department has come together and achieved its goal of being even better than the year before.

If you would like to come to the concert this year, do visit the Cadogan Hall website to get more information on repertoire and information on how to buy tickets. The concert this year takes place on Monday, 30th March from 7:30pm.

https://cadoganhall.com/whats-on/wimbledon-high-school-2020/

Rosie, Year 11, shares her recent WimTalk with us, discussing issues surrounding the way Britain remembers its past to shape its future.

September 2nd, 1945, Tokyo Bay. On the deck of the American battleship USS Missouri, the Japanese Instrument of Surrender document was signed by representatives from Japan, the United States, China, the United Kingdom, the USSR, Australia, Canada, France, the Netherlands, and New Zealand. World War Two was officially over. This ceremony aboard USS Missouri lasted 23 minutes, and yet the impact of what it represented rings on to today, almost 75 years later.

Now, in 2020, Great Britain has not moved on the Second World War – far from it. Everywhere in Britain, wartime memorials and museums can be found, remembering the half a million soldiers and civilians who lost their lives. Most British people have relative who fought in or experienced the war, and there are few who would not recognise the phrase ‘We shall fight on the beaches’ from Churchill’s most famous speech. And this prominent remembrance is not just confined to the older generations: It is an integral part of every child’s education too. Hundreds of books, TV programmes, podcasts and films have documented the war with great success – even recently. The modern economy, too, remembers the war, with Britain making the final war loan payment to the United States only 14 years ago in 2006. Overall, the memory of the Allied victory in the Second World War – “our Finest Hour” – inspires the national sense of pride in our military history that has become a rather defining British characteristic.

But the question is: why does Great Britain cling on to the Second World War more than any other nation involved? And is this fixation justified, or is it time to move on?

One perspective is that the British viewpoint of the Second World War is bound to be different because of geography. The triumph of physically small island nation prevailing in war is something we can celebrate and take pride in. For other nations involved – larger landlocked countries with shifting borders – this is less easy. For example, Germans today are less inclined to look back, not only because of the radical changes in society since the Third Reich or lack of a victory to celebrate, but also because modern Germany is physically different to the earlier Germany of the Kaisers, Weimar, Hitler and the divided states of the Cold War. Instead, Germany today looks forward, not backwards, which some would argue has allowed it to become the economic giant on the world stage that it now is.

And that’s another thing – how much has Britain changed since the Second World War? Of course, it has modernised along with the rest of the world: politically, economically, and physically, but so many of the same institutions remain as were present in 1939. Our democratic government, our monarchy, our military and traditions have survived the test of worldwide conflict twice in one century, the collapse of the British Empire and the Cold War in a way that those of France, Spain and Italy have not.

The Second World War was a clear clash of good vs bad – peace vs aggression. Britain was not directly attacked by Hitler but stepped up to honour a promise to defend Poland against invasion for the greater good. Remembering the Second World War makes Britain proud of these national values, as had Chamberlain not roused from his policy of appeasement and committed Britain to the sacrifice of money, empire and life, had Churchill not fortified the nation’s most important alliance with Roosevelt, the world would certainly be a very different place today. And so, if a nation’s psyche comes from the values and institutions it possesses that have stood up throughout history, is it really any wonder Brits take pride in looking back?

On the other hand, perhaps after so many years it’s time to recognise that we are not, in fact, the same Britain that we were in 1945. In 1944, British economist John Maynard Keynes spoke at the famous Bretton Woods conference. He said that the Allies had proven they could fight together, and now it was time to show they could also live together. In achieving this, a genuine ‘brotherhood of man’ would be within reach. At this conference, the IMF and World Bank were created, soon followed by the UN, to promote peace and prevent the kind of economic shocks that led to war in the first place. But at the same time, these organisations were a convenient way for the main Allied powers to solidify their power and privileges. Since then, a European has always headed the IMF, and an American the World Bank. The UN Security Council is dominated by the five permanent members, whose privileged position, some say, is nothing but a throwback to the power distribution on the world stage of 1945. By clinging on to the war, are we really clinging on to the idea that Britain is still a leading power, and modern economic giants such as Germany and Japan do not deserve to disrupt the power structure of 1945? We pour so much money into Britain’s defence budget to maintain this powerful status – into remembered threats and sometimes archaic strategies: submarine warfare, aerial dogfighters and manned bombers. The Second World War was certainly a catalyst for change across the globe. Perhaps now, Britain’s inability to let go of these old power ideals and designated roles of nations prevents us from achieving the ‘brotherhood of man’ that, in 1944, Keynes dared to dream of.

We are told that the value of history is to ‘learn a lesson’ to prevent us from repeating the same mistakes again. But there is an argument to say that this concept is a consistent failure. So many conflicts around the world seem to be caused by too much remembering: refreshing tribal feuds, religious division, border conflicts, expulsions and humiliations. Doesn’t remembering cause Sunni to fight Shia or Hindu to fight Muslim? Is it memory that maintains dispute in the Balkans, the Levant, Mesopotamia? Perhaps the emotion sparked by remembering the details of our past is better left in history when it has the capability to spark aggression, conspiracy theories and irrational anger. Today’s politics of identity seem provocative enough without being fuelled by history, so perhaps we should heed Jorge Luis Borges who wrote: ‘The only vengeance and the only forgiveness is in forgetting’. This advice has been proven to work over time – Nelson Mandela’s philosophy in 1990s South Africa was to focus on ‘truth and reconciliation’ and draw a line under his country’s recent history – closure. Can Britain not find closure on the 20th century?

What I can conclude is that there are two perspectives to take on this statement: there are some who hold onto our history as a lesson for the future, as a reminder of the importance of peace and action for the greater good, who will never be able to forget the Second World War because of the core British values that it represents. And then, there are those who think it is time to let go of the past, and adapt our nation’s values to suit our current position in the quickly-changing world that we live in. And so, the only question I have left to ask is: which are you?

Sofia, Year 9, discusses what dreams are and why they happen.

When you think of the word “dream”, many questions may pop into your head such as ‘what do they mean?’ and ‘what are they for?’ and perhaps ‘can they predict my future?’ I guess the best way to describe a dream is a story or sequence of images your mind creates while you are asleep. Except of course there is a lot more to it…

It is thought that people in the third millennia in Mesopotamia were the first to record their dreams on wax or clay tablets and over 1000 years later Egyptians made themselves dream books, which also listed their potential meanings. Priests would be the ones to interpret these since they were written in hieroglyphics. Interpreters were looked up to, as they were blessed with this divine gift.

Interestingly, in the Greek and Roman era, dreams were interpreted in a religious context, thinking gods or even those from the dead were sending them direct messages. They believed dreams forewarned and they even built special shrines where those who sought a message would go to sleep.

In China, dreaming was also seen as a place where your spirit and soul left your body and went to a different world while asleep. If you were awoken, your soul may fail to return to your body. In the Middle Ages, dreams were considered to be the devil’s dirty work and fill the humans’ minds with malicious thoughts while at their most vulnerable state.

Dreams can sometimes be exciting, terrifying, boring and just plain random, and although it may not feel like it, we have multiple dreams in one night that actually only last approximately 15 minutes. It’s hypothesized that everyone dreams, even though people who don’t remember their dreams may think they don’t dream[1]. Within 5 minutes of waking up, you usually forget 50% and by 10 minutes almost 90% is gone[2].

Dreams typically involve elements from life such as known people or familiar locations. And yes, it has been proven that your brain is incapable of “creating a new face”. They can also allow people to act out certain scenarios that wouldn’t happen in real life and make you feel incredibly emotional if it is vivid enough. In 1899, Sigmund Freud wrote a study “Interpretation of Dreams” which has been controversial among other experts. He states that we only dream to fulfil wishes, but many have disagreed. The Continual Activation Theory explains that we dream to keep our brains working and to consolidate memories, so that when data is needed from memory storage, we have it, but it’s just expressed in a different way while we dream. It is also suggested that we dream to rehearse and practise. Have you ever had a nightmare of being chased by a bear or even a criminal? These have been proven to be very common and challenge your instincts in case you ever do come across a dangerous situation in your life.

The scientific study of dreams is called oneirology (derived from Greek word ‘oneiron’) Dreams mainly occur in the REM (rapid eye movement) stage of sleep when brain activity is high and feels similar to being awake; it occurs within the first 90 minutes of falling asleep. During this stage, the pons in the brain shut off signals to the spinal cord causing you to be immobile while sleeping. When the pons doesn’t shut down the spinal cord’s signals, people will act out their dreams which of course could be dangerous, perhaps if you run into a wall or fall down a staircase.

This is known as REM sleep behaviour disorder, which is rarer than sleepwalking. Even though we are immobile, the brain is very active, and you could still move and accidentally hit your sister in the face thinking you’re in a netball match. The blue represents inactive parts in the brain during REM in the image shown. Linking back to a previous point, an additional reason we may dream is to forget. This may sound confusing, but our brain creates thousands of connections by everything we think and do. A neurobiological theory known as Reverse Learning told us that during REM sleep cycles, the neocortex reviews the connections and ignores unnecessary ones, preventing your brain from being overrun with useless connections.

Even if we never know the real reason why dreams happen or whether they have any significance, it is possible that we will eventually one day find out due to developing technology. However, they may always remain somewhat a mystery to us, but hopefully, the next time you go to bed, you’ll maybe consider the complex aspects of science behind them.

[1] https://www.discovermagazine.com/mind/does-everyone-dream

[2] https://www.manifatturafalomo.com/blog/sleep-tips/15-incredible-facts-about-sleep/

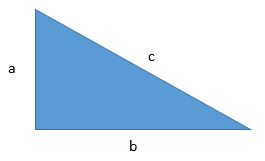

Vishaali, Year 10, looks behind the proof of one of the most famous mathematical theorems – that of Pythagoras’ theorem.

A theorem is a mathematical statement that has been proven on the basis of previously established statements. For example, Pythagoras’ theorem uses previously established statements such as all the sides of a square are equal, or that all angles in a square are 90°. The proof of a theorem is often interpreted as justification of the statement that the theorem makes.

On the other hand, a theory is more of an abstract, generalised way of thinking and is not based on absolute facts. Examples of theories include the theory of relativity, theory of evolution and the quantum theory. Take the theory of evolution; this is about the process by which organisms change over time as a result of heritable behavioural or physical traits. This is based on undeniable true facts, but more from experience and from an abstract way of thinking.

It is also important not to confuse mathematical theorems with scientific laws as they are scientific statements based on repeated experiments or observations.

You have probably all heard of Pythagoras’ theorem, one of the simplest theorems there is in mathematics, that is relatively easy to remember. Given that it’s so easy to remember and to learn, wouldn’t it be an added bonus to know exactly how this theorem came to be?

The theorem, a²+b²=c², relates the sides of any right-angled triangle enabling you to find the lengths of any side, given you have the lengths of the other two.

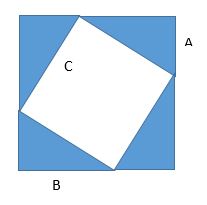

This whole theorem is based on a triangle like this:

These four right-angled triangles are exactly the same just rotated slightly differently to create this shape:

Two shapes have been made by putting these triangles in this order. A big square on the outside, and another slightly smaller square in the middle. As all these triangles are the exact same you can label them A, B and C.

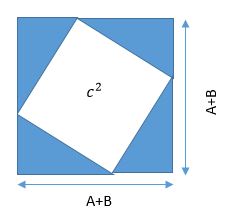

You can tell from the labels the triangles have been given, that the bigger square would have the sides (a+b), and the smaller triangle in the middle will have sides of c. Therefore we know the area of the smaller square is c² :

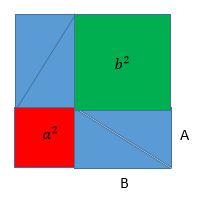

Using the exact same four triangles, we can rotate and translate them to create a slightly different shape:

Now two more squares have been added to this shape. We can call them a² and b².

Thinking back to the shape we made before, we can also see that the length of this shape is also (a+b). As we know we used the same four right-angled triangles for the shape before and now, we can infer that the two squares a² and b² are exactly the same as the square from the first shape, c². Hence we get Pythagoras’ theorem, a²+b²=c²:

https://www.livescience.com/474-controversy-evolution-works.html

https://www.askdifference.com/theorem-vs-theory/

Martha, Year 8, discusses gender discrimination in sports and outlines recent developments that have helped to move the industry towards greater equality.

Gender discrimination in sports has long been a controversial topic due to inequality regarding wage, audience viewing numbers, and the overall range of opportunities that exists between men and women in the arena of competitive sports. Gender discrimination is still an issue in the 21st century; more people still will watch men’s football than women’s, and women’s football is rarely discussed in the media.

Many people think that if there was to be more media coverage or sponsorship of women’s sport it would be more popular with audiences. The media says that if women’s sport generated more interest in the first place then they would invest more time and money into it.

Most people agree on what it takes to make a sport successful: commercial appeal, interest from the general public, and media coverage. The fact is that sponsors are less likely to promote teams or individuals who don’t have lots of media exposure, and not many women in sports do. The Women’s Sport and Fitness Foundation found that in 2013, women’s sports received only 7% of coverage and a shocking 0.4% of commercial sponsorships[1].

This is a vicious circle, as viewers want to watch sports at the highest professional standard, and sponsors want to be associated with the best athletes. Because of the lack of sponsorship many female athletes, even those who represent their countries, have to fit training around employment. Many male athletes, however, would have their sport as their profession and as such would not need to divide their training regime with other work. Women who are paid usually earn less than their male colleagues; the Professional Golfers’ Association, for example, offers 256 million dollars in prize money; the women’s association offers only 50 million[2]. This inequality also happens in pay for coaches of women’s teams compared to male teams.

Things are changing, and there is energy behind equality for the industry. The English women’s cricket team became professional in 2014, signing a two-year sponsorship deal with Kia after winning many Ashes contests. The Wimbledon Championships started awarding women the same amount of prize money as men in 2007[3]. Most importantly, the opinions of sports fans seem to be changing: 61% of fans surveyed by the Women’s Sport and Fitness Foundation said they believed top sportswomen were just as skilful as their male equivalents and over half said women’s sport was just as exciting to watch[4].

The road to equality is not an easy one, and there are many different aspects to achieving this; pay, opportunity and recognition. Lots have been done in more recent years to address aspects like equal pay, but there is still more to do to gain full equality. When the Women’s World Cup has as much excitement, sponsorship and audience engagement as the Men’s World Cup, then we are nearer to having achieved equality in sport.

References

[1] https://www.womeninsport.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Womens-Sport-Say-Yes-to-Success.pdf

[2] https://www.telegraph.co.uk/golf/2018/12/17/top-ten-women-golfers-earn-80-per-cent-less-men/

[3] https://www.cnbc.com/2019/09/11/despite-equal-grand-slam-tournement-prizes-tennis-still-has-a-pay-gap.html

[4] https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/07/27/why-professional-womens-sport-is-less-popular-than-mens

Sophie, Year 9, asks if and how music can impact our mental and physical health.

Music is everywhere. Wherever we go, no matter where, there will be some sort of tune or melody coming from someplace or another. Virtually all species, from the most primitive to the most modern, make music. In tune or not, our species sing and play, or clap and drum. Music is a cardinal aspect of our lives. The human brain and nervous system are programmed to distinguish music, rhythm and tones from noise and other sounds. Is this a biological accident, or does it serve a purpose? There might be no definite answer, but one could suggest from studies that music may enhance human health.

Music is everywhere. Wherever we go, no matter where, there will be some sort of tune or melody coming from someplace or another. Virtually all species, from the most primitive to the most modern, make music. In tune or not, our species sing and play, or clap and drum. Music is a cardinal aspect of our lives. The human brain and nervous system are programmed to distinguish music, rhythm and tones from noise and other sounds. Is this a biological accident, or does it serve a purpose? There might be no definite answer, but one could suggest from studies that music may enhance human health.

Music has always been a source of expressing people’s feelings, venting emotions and communicating with others, through words and notation. The soothing power of music is well-identified – it can have a big impact on our mental health. It can also have a strong link to our emotions, and, as a result, can be a brilliant form of stress relief. Listening to music can be relaxing for our mind and bodies, especially slow, quiet classical music. This type of music has a beneficial effect by slowing the pulse and heart rate, lowering blood pressure and decreasing the levels of stress hormones. For example, studies[1] show that listening to music with headphones has reduced stress and anxiety in hospital patients before and after surgery. Listening to music can also relieve depression and increase the self-esteem of elderly people.

Music can also absorb our attention and can get rid of any distractions. This means it can be a focus technique as it keeps our mind from wandering. However, music with no structure and no form can have a negative impact on our emotions and can be unsettling and irritating. This is why gentle music with a simple melody is also more comforting. Familiar melodies bring a sense of calmness, awareness and it can be more comforting. The sounds of nature often are incorporated into CDs specifically to target relaxation. The sound of water or leaves or birdsong can be soothing for some. It can help picture calming images and help our minds slow down.

As well as calming, and being a stress relief, music can be a source of happiness. It has the ability to make people of all ages feel cheerful and energetic and could even lift the mood of people with depressive illnesses. A recent study[2] announced that scores of depressive symptoms (extending from 0-60) improved on average 4.65 more with the music therapy than standard care alone. In 2006 a study of sixty adults with chronic pain found that music was able to reduce pain and depression[3]. In 2009 there was another study stating that music assisted relaxation can improve the quality of sleep in patients with sleeping disorders[4].

As well as calming, and being a stress relief, music can be a source of happiness. It has the ability to make people of all ages feel cheerful and energetic and could even lift the mood of people with depressive illnesses. A recent study[2] announced that scores of depressive symptoms (extending from 0-60) improved on average 4.65 more with the music therapy than standard care alone. In 2006 a study of sixty adults with chronic pain found that music was able to reduce pain and depression[3]. In 2009 there was another study stating that music assisted relaxation can improve the quality of sleep in patients with sleeping disorders[4].

Some skilled composers manipulate our emotions by knowing what the listeners’ expectations are and controlling when the expectations may (or may not) be met. Composers also change their music to fit our emotions. They will use specific techniques to make us feel a certain way. These techniques could include; tempo (a fast tempo could provoke an energetic feeling, whilst a slow tempo might induce feelings of sadness or tiredness), tonality (major linked to positive and minor negative), dynamics (forte – loud – may portray bold or confident, whilst piano – quiet – could be more subtle).

Some of these factors may cause the listener to maybe start swaying side to side or tapping our feet or nodding our head. This is connected to the dopamine drug which is linked to the pleasure of music. Neuroimaging studies have proven that music can activate the brain areas typically associated with emotions. The deep brain structures that are part of the limbic system like the amygdala or hippocampus as well as the pathways that transmit dopamine (for pleasure associated with music listening). The relationship between listening to music and the dopaminergic pathway is what is behind the ‘chills’ that people claim to experience whilst listening to music[5]. These chills are physiological sensations, like hairs getting raised on your arms, goosebumps down your leg and ‘shivers down your spine’ that is linked to chills.

Whatever your musical preference, understanding that music has a significant impact on our mental and physical health is central to knowing more about the immense power this art has on us. As Napoleon once said, “music is what tells us the human race is greater than we realise.”

References

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-33865448

[2] https://www.nhs.uk/news/mental-health/music-therapy-helps-treat-depression/

[3] https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/music-and-health

[4] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24441233_Music-assisted_relaxation_to_improve_sleep_quality_Meta-analysis

[5] https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/51745/why-does-music-give-us-chills