In WimTeach this week, Rachel Evans, Director of Digital Learning & Innovation explores our initial response to ChatGPT.

Across many sectors of the economy and all across the world people are feverishly discussing ChatGPT. In November 2022, OpenAI launched an open access version of their latest generative AI in the form of a chatbot, with an interface that looks like a messaging app. We hasten to sign up, try it out and speculate about what this means for our collective futures. When the server is busy, as it so often is now, it amuses us with jokes or a poem. Each time I can’t help wondering if a human actually wrote that bit, to entertain and reassure us. Is it the start, or end, of everything?

In conversation with colleagues, students, parents and experts, we have set out three areas for research, discussion and consideration before we take action about ChatGPT.

Academic integrity

This is the immediate concern for many educators, and students and parents too. Quite simply, that students will use the AI to cheat, generating answers and essays which they can pass off as their own. This is a (fairly) novel software system, but this problem is certainly not new. In terms of technology, it’s one which MFL teachers have been wrestling with for some years now, since Google Translate first appeared. The challenging conversations we have when a teacher knows, from their knowledge of the pupil, that the work may not be their own will continue.

During my reading for this article, I came across this phrase in a blog by the education leader Conrad Hughes: “Artificial intelligence should be where thinking starts, not where it ends.” This seems to me a good place to start. The value we place on scholarship and curiosity means that we can hold open conversations with students about the importance of doing the intellectual work of developing the foundations of your own knowledge, rather than resorting to an inauthentic response. Our focus on metacognition will stand us in good stead when having conversations about how learning happens. That discussion will lead, in turn, to our next area of research and consideration.

Positive uses for AI in education

If this AI – or others like it – fulfils its early promise, there may be positive and exciting uses in education. For students, there is the opportunity to use the text generated by the AI to test out their own critical thinking skills and analysis, or to find out how accurate their input needs to be to get a good output. For teachers, there is potential to use AI as assistive technology to support the creation of teaching materials, marking or analysis of data. We are already using AI to assist us in small ways – every time we use Word Editor or make a PowerPoint presentation smarter. As always, the goal is to achieve time savings which we can then spend in those important face-to-face interactions with students or giving rich and timely feedback. We would be remiss not to explore those opportunities, but as in all organisations, we will need to carefully select those uses which match our existing aims and values. We will evaluate carefully the cost and benefits, literal and figurative, before proceeding.

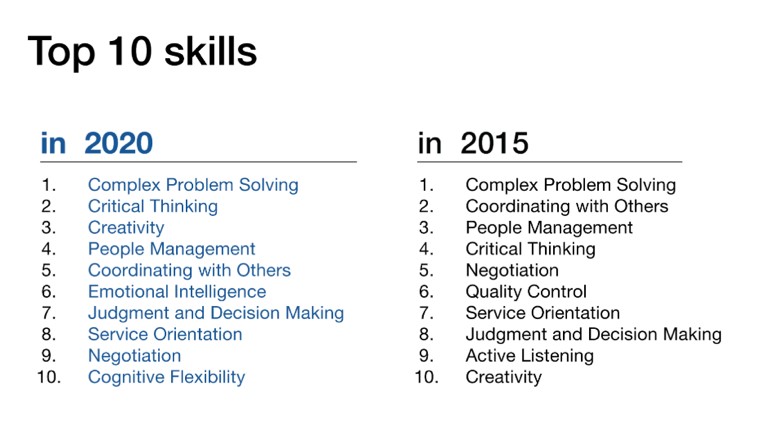

New skills & Futures

Popular books about AI such as Human Compatible by computer scientist Stuart Russell (2019), and Daniel Susskind’s A World Without Work (2020) both paint convincing portraits of a future where AI has dramatic effects on the economy. Some of the media narrative around ChatGPT draws on these ideas – and we hear from friends and parents in various sectors that uses are already being found for the chatbot in creating content for websites and social media and writing analytical reports involving large amounts of source material – but mediated by a human who will critically assess, improve and extend the text. Microsoft’s further investment in OpenAI seems to signal an intention to find integration for this kind of AI in the apps that we use every day. Other commentators are unconvinced – but whether it is this AI or a later iteration, this is a change that will surely come. It is vital, therefore, that we engage students with this technology. We want to ensure that they learn how to use it to extend and enhance their own productivity and capabilities, and that they can bring their own knowledge, experience and critical capabilities to bear. We will be discussing how we incorporate this technology into our digital and study skills, and Futures programme.

There are so many ideas and approaches to explore within these three areas of concern, but also around pedagogy, the future of examination and assessment. I see the opportunities this term for staff and students to discuss the issue from all angles as the best way to shape our approach in the coming months. We need to encompass not only practical aspects of the impact of this technology, but ask questions too about the nature of ‘Big Tech’ and the cost of such AI tools both in terms of sustainability and ethics and equality. It is the start of the thinking and the start of a conversation.

It seems to me that the only suitable response to a popular narrative of upheaval and radical impact around this technology is to hold steady: to pause, read, research and discuss. To have the humility to recognise that we can’t predict the future. To hold firm to our values and approach to learning. I feel confident that our open, dialogic and human approach to education will ensure that – together – we find the right response to this technology for our school.