Rebecca Brown, GDST Trust Consultant Teacher for Maths and WHS Maths teacher, reviews part of Steve Chinn’s paper on The Trouble with Maths – a practical guide to helping learners with numeracy difficulties.

Each learner needs to be understood as an individual and the teaching style and lessons adapted to suit each individual learner.

Is it Dyscalculia or Mathematical learning difficulties? However it may be described, challenges with Maths create anxiety amongst children and adults alike.

The 2017 National Numeracy booklet, ‘A New Approach to Making the UK Numerate’ stated that ‘Government statistics suggest that 49% of the working-age population of England have the numeracy level that we expect of primary school children’. This indicates that having a difficulty with maths should not automatically earn you the label ‘dyscalculic’. So what does it mean to be successful at Maths and why does it make so many people anxious?

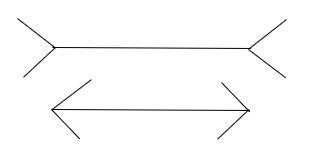

Two key factors which aid learning are ability and attitude. Some learners just feel that they can’t do Maths. They feel helpless around Maths. Maths can create anxiety and anxiety does not facilitate learning. Ashcraft et al (1998) have shown that anxiety in Maths can impact on working memory and thus depress performance even more.

More recent research using brain scanning has found that regions in the brain associated with threat and pain are activated in some people on the anticipation of having to do mathematics.

The key question, when faced with a learner who is struggling with learning maths is, ‘Where do I begin? How far back in Maths do I go to start the intervention?’ This may be a difference between the dyscalculic and the dyslexic learner or any learner who is also bad at maths. It may be that the fundamental concepts such as place value were never truly understood, merely articulated.

None of the underlying contributing factors are truly independent. Anxiety, for example, is a consequence of many influences.

Chinn favours the definition of dyscalculia to be ‘a perseverant condition that affects the ability to acquire mathematical skills despite appropriate instruction.’

A learner’s difficulties with Maths may be exacerbated by anxiety, poor working memory, inability to use and understand symbols, and an inflexible learning style. Chinn suggests adjustments to lessons to assist difficulties in maths based on four principles:

- Empathetic classroom management

- Responsive flexibility

- Developmental methods

- Effective communication.

In short, the issue is that not every child or adulty who is failing in Mathematics is dyscalculic. Even for those who do gain this label, it does not predict an outcome or even the level of intervention but as Chinn suggests whatever teaching experiences this pupil has had, they may have not been appropriate.