Andrea T, Academic Rep, looks at the nature of globalisation and whether with the context of our history we can consider it a ‘new phenomenon’

Globalisation is an ever-present force in today’s society. Scholars at all levels debate the extent of its benefits and attempt to discern what life in a truly globalised world would entail. But where did it all begin? A comparison of the nature of colonialisation and globalisation aid our understanding of this phenomenon’s true beginning, yet no clear conclusion has been reached. This leads us to the matter of this essay, an attempt at answering the age-old question: “Is globalisation a new phenomenon?” Though there are striking similarities between both colonialisation and globalisation, I do not believe we can see them as them one and the same. Due to the force and coercion that characterised colonisation’s forging of global cultural connectivity, and the limitations of colonial infrastructure, we cannot consider it true globalisation. Therefore, though imperfect, the globalisation of the modern world is its own new phenomenon.

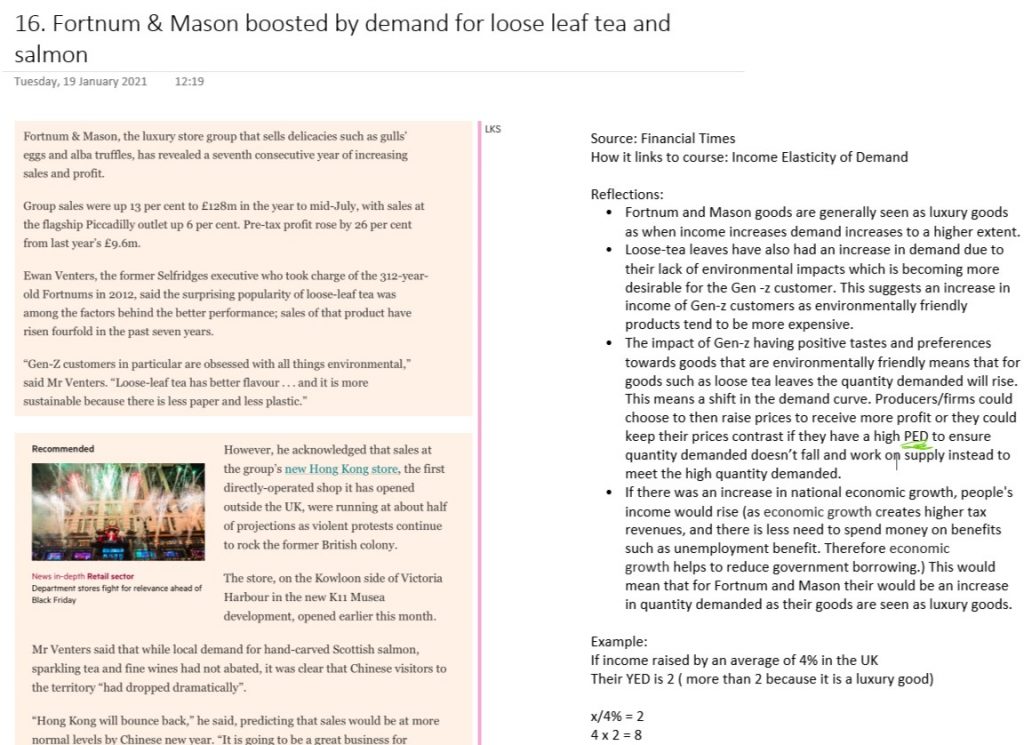

Before I can delve into the comparisons of colonisation and globalisation,

we must first gain a common understanding of the characteristics of both. There

is no set definition for globalisation, though most definitions portray it as

an agglomeration of global culture, economics and ideals. Some also allude to

an ‘interdependence’ on various cultures and an end goal of homogeneity. (One

could certainly debate whether this reduction of national individuality is

truly a desirable goal, but that is sadly not the purpose of this essay.) Furthermore,

for the purpose of this argument, homogenisation is taken on the basis of

equality; equal combination of culture forming a unique global identity. And

the focus of this essay will be the sociological aspects of globalisation, as

opposed to the nitty gritty of the economics.

Though we are far from a truly homogeneous world, we

certainly see aspects of it in the modern day. With an increase in

international travel and trade, catalysed by the rise of technology and

international organisations, we have seen the emergence of mixed cultures and

economies. Take for example the familiar ‘business suit’. Though it is seen as

more of a western dress code, all around the globe officials and businesspeople

alike don a suit to work, making them distinctly recognisable. One might

however consider how truly universal this article of clothing is. Its first

origins are found in the 17th Century French court, with a

recognisable form of the ‘lounge suit’ being seen in mid 19th

Century Britain, establishing it firmly as a form of western dress. We then

later see, with its rise to popularity in the 20th century (as

international wars brought nations closer), the suit and many other western

trends adopted across the globe (see picture below). Considering the political

atmosphere of the time, and the seeming dominance of the West, we may doubt

that the adaptation of the suit was an act of mutual shared culture. And yet we

see the ways in which the suit has been altered as it passed to different

cultures. Take the zoot suit, associated with black jazz culture, or the

incorporation of the Nehru jacket’s mandarin collar (Indian origin) into the

suits popularised by the Beatles. Though it still remains largely western, with

the small cultural adaptations we can see how something can be universalised

and slowly evolve towards homogenisation. In this way, a symbol as simple as

the suit can be representative of a globalising world.

This is also where we start to see the link between

colonisation and globalisation form. Trade formed an essential part of each

colonial empire – most notably, the trade of textiles. Through the takeover of

existing Indian trade (India in fact formed 24% of world trade prior to its

colonisation), British-governed India exported everything from Gingham to tweed, and had a heavy influence on the style of the

society’s elite, taking inspiration from the traditional Indian methods of

clothes-making. Furthermore, this notion of the business suit can be seen as

early as when Gandhi arrived in Britain (seeking education on law), dressed in

the latest western trends. However, though the two do certainly share

characteristics, we must consider the intent behind this blend of culture. The

ideal of globalisation suggests an equality that is not echoed in colonisation.

Gandhi did not wear western styles because of his appreciation of British

fashion trends, but instead knew that it was far easier to assimilate if you looked

and acted the same. Similarly, influence of Indian dress on British dress was

not from a place of appreciation either, but from one of exploitation.

Therefore, though the sharing of culture is present in both globalisation and

colonisation, one cannot consider them to be the same due to the underlying

intent. Furthermore, as the intent in modern day globalisation is in some ways

similarly exploitative, one cannot consider the world truly globalised, but

rather globalising, through a process one could still consider a new

phenomenon.

Another aspect of globalisation we can consider

is the role of the media. McLuhan, a 20th century Canadian

professor, capitalised on this by proposing the idea of a ‘global village’ that

would be formed with the spread of television. His theories went hand-in-hand

with the ideas surrounding ‘time-space compression’ that have come about due to

travel and media. And McLuhan was right, with a newly instantaneously connected

world we have become more globalised. With the presence of international

celebrities, world-wide news and instant messaging we have the ability to share

culture and creed, and though far from homogenous we can certainly see small

aspects of global culture beginning to form. Due to this dependence of

globalisation on technology it is therefore hard to view colonisation as

early-stage globalisation. But one can make one distinguishing link. One could

argue: the infrastructure implemented for trade routes served as the

advancements in technology of the imperial time. Similar to air travel, with the

creation of the Suez Canal and implementation of railways, it was easier to

traverse the globe. This is what further catalysed open trade and contact

between different nation states, one of the most recognisable traits of

globalisation. However, despite this, the trade routes did not improve

communication anywhere near to the level we see today, and the impact

technology has had on the connectivity of our globe is too alien to

colonisation for the two to be considered the same. In terms of

interconnectivity, the form of globalisation we see today is entirely novel,

and though they have the same underlying features, the difference between the

two remains like that of cake and bread.

Another aspect of globalisation we can consider is the

spread of religion. Religion is an incredibly important aspect of a country’s

culture, defining law and leadership for hundreds of years. The American

political scientist Huntington explored religion and globalisation in his work:

‘The Clash of Civilisations’ (1996) in which he put forward the following thesis:

due to the religio-political barriers, globalisation will always be limited.

But events have challenged this. There has been a rapid

spread of religion around the world due to the newfound (relative) ease of

migration and the access to faith related information through the internet. From

London (often dubbed a cultural ‘melting-pot’) to Reykjavik (rather the

opposite), we see Mosques and other religious institutions cropping up. With the

lack of religious geographical dependence, we see the homogenising effect of

globalisation. This is also to some extent echoed in colonisation. During the

years of the British Empire, colonisation followed a common narrative of the

white saviour. Missionaries preached a new and better way of life, supposing that

the application of Christian morals and values would help develop the ‘savage’

indigenous tribes. This attempt at integrating western Christian culture into

the cultures present across Africa and Asia shows an early attempt at a homogenised

culture. However, though there was certainly some success in the actions of the

missionaries (as seen with the establishment of many churches across South

Africa), the aggressive nature of this once again contradicts the fairness

implied in the concept of a homogenous culture, and globalisation remains a new

phenomenon.

One cannot dispute that colonisation does share a number of

characteristics with globalisation. From free trade to new infrastructure to

the mixing of culture through religion and fashion, we can certainly see aspects

of a globalising world. And yet the forceful intent of the homogenisation of

cultures seen in the colonial era, removes it from being the true

interconnectivity of nations. This is not to say that the world today is free

of this intent, but the way in which our world today is globalising is approaching

the ideal of globalisation more closely than colonisation ever did, and there

is a distinct enough difference between the two that one cannot consider

colonisation to truly be an early-stage globalisation. Furthermore, the world

today relies so heavily on technology as a facilitator of globalisation that

any notion of globalisation in the 19th century cannot be considered

one and the same. Therefore, the globalisation of our day and age can be

considered its own new phenomenon.

Bibliography

“Cultural Globalization.” Encyclopædia Britannica,

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.,

www.britannica.com/science/cultural-globalization.

“Globalization Is a Form of Colonialism.” GRIN,

www.grin.com/document/287753.

“Globalization versus Imperialism.” Hoover Institution,

www.hoover.org/research/globalization-versus-imperialism.

Steger, Manfred. “2. Globalization and HISTORY: Is Globalization a New

Phenomenon?” Very Short Introductions Online, Oxford University

Press,

www.veryshortintroductions.com/view/10.1093/actrade/9780199662661.001.0001/actrade-9780199662661-chapter-2.

“What Is Globalization?” PIIE, 26 Aug. 2021,

www.piie.com/microsites/globalization/what-is-globalization.

Maddison, Angus “Development Centre Studies The World Economy Historical

Statistics: Historical Statistics” OECD Publishing, 25Sep. 2003,

Chertoff, Emily. “Where Did Business Suits Come from?” The

Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 23 July 2012,

www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2012/07/where-did-business-suits-come-from/260182/.