Mrs Nicola Cooper, Teacher of Biology, looks at how the introduction of a new specification can provide an invaluable opportunity to reassess outcomes

I am a self-confessed Biology geek and my love for the subject knows no bounds. Its breadth, its relevance and the sheer beauty of the complexity that can arise from a few simple components is endlessly fascinating to me. Moreover, I love teaching Biology. Sharing my passion for the living world is energising and is a wonderful way of connecting in new ways with the key ideas and concepts that underpin the living world.

It has therefore been a source of frustration that over the years I have encountered many people whose experience of learning Biology at school is a negative one. A not-uncommon view seems to be that whilst many people have an innate interest in learning about the living world and our place within it, there is a perception that the study of Biology is characterised by mindless rote learning of a seemingly endless body of ‘facts’. If this perception is then reinforced by teaching that is built around imparting knowledge, then no wonder much of the joy, excitement and inspiration is lost.

This is something we are very aware of at Wimbledon High School and as a department we work hard to encourage our students away from rote learning towards a deep understanding of key concepts that they can then apply in a wide range of contexts.

So, what does this look like in practice? Well, this year we have been given the opportunity to think much more deliberately about this question, with the introduction of the new GCSE specification. In devising new schemes of work, we began by challenging ourselves to think expansively (during a wonderfully lively brainstorming session) with the question ‘What outcomes do we want for our year 9 students?’ What emerged from that discussion was not a long list of ‘facts’ that we want our students to be able to recall but rather three key themes;

- A sense of wonder about the living world

- A questioning approach

- An ability to solve their own problems.

These have been our guiding principles when planning lessons for Year 9 (the first cohort following the new course). We have deliberately chosen not to cover topics in a linear way but have (quite literally) cut up the specification and rearranged topics so that central concepts can be explicitly linked with related contexts. The aim being, right from the start of the course, to model how knowing and understanding a few key ideas can allow students to pose and then answer their own questions.

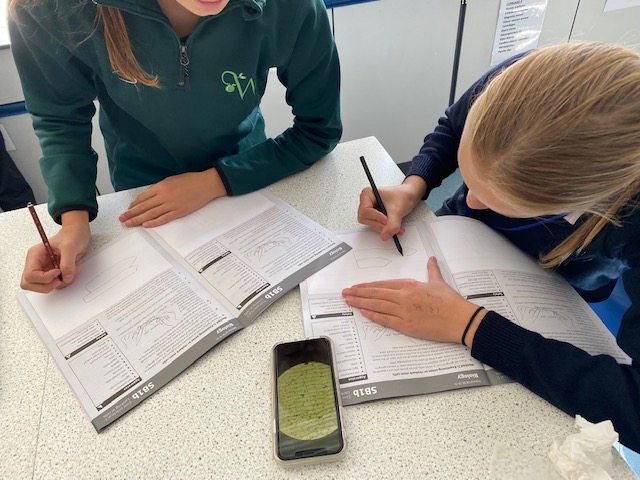

Drawing onion cells from a photo taken down a microscope

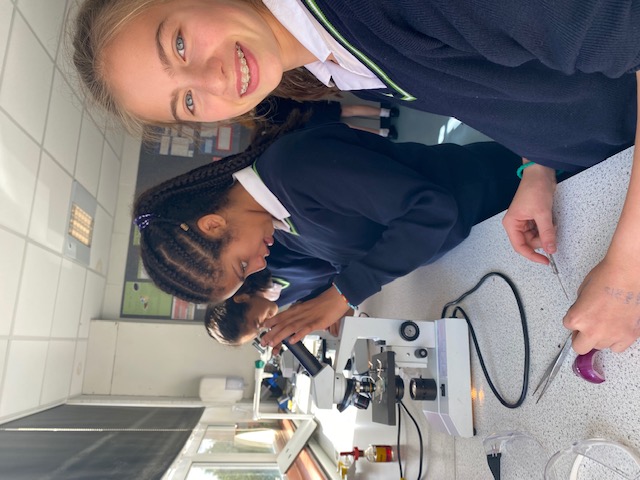

In our opening topic of health and disease we start each lesson with a question such as ‘What happens when you get ill?’ and ‘Is being healthy the same as being ill?’. We have looked at medieval views on health and disease and linked our discussions to very recent experiences of the Covid 19 pandemic. We are also using the context of communicable diseases to explore the key concept of cell structure and function. Encouragingly, our students have responded very positively and there has been a definite buzz and the fizz of excitement in my Year 9 lessons.

Zoe in year 9 said, “I found today’s lesson really helpful. I think we all gained an important biological skill that we will use throughout Biology”, while Penelope (year 9) said “I found it very interesting and rewarding, especially because we got to set up the experiment ourselves”.

From a teaching perspective it has been stimulating and refreshing to be reminded of our purpose and as a department we are excited to see how the students continue to develop and flourish as they move through the rest of the year and on to their further studies In Biology.

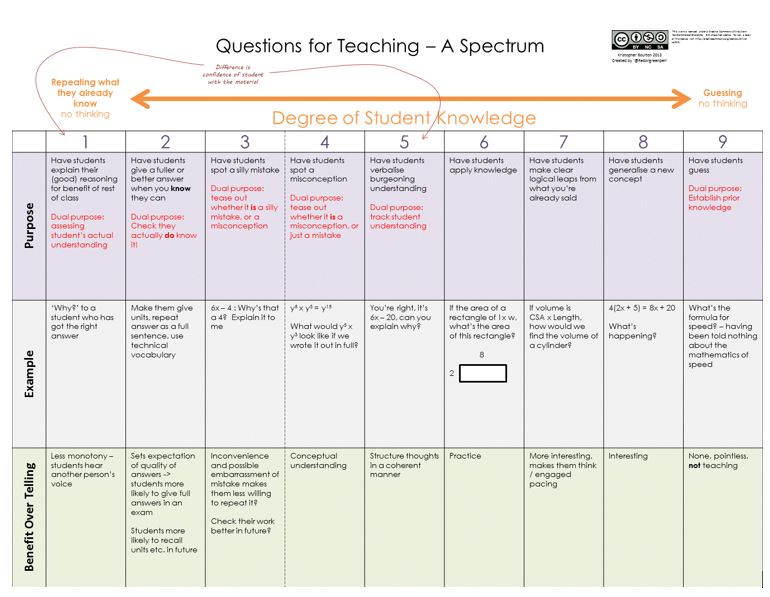

addresses that the question is not why questions are better, it is when. He concluded that: ‘questions can be very effective tools of teaching, but they must be used with incredible care.’ A very structured grid of various question types concluded by him and another blogger can be found here:

addresses that the question is not why questions are better, it is when. He concluded that: ‘questions can be very effective tools of teaching, but they must be used with incredible care.’ A very structured grid of various question types concluded by him and another blogger can be found here: