In WimLearn this week, Year 11 student Laura K researched the Convivencia, a lesser-known part of the Spanish history.

During a visit to Toledo in Spain I noticed part of the Toledo Cathedral was a mosque and thought that this was unusual. Only later did I realise that this was a remanent of the Muslim presence in the city during what I now have learnt is a period known as the “Convivencia”. It was interesting to learn that there was a significant Arabic presence in Toledo and that their history and cultural contributions to Spanish culture are not widely discussed or recognised. This is also the case for Jewish culture. This topic was a fascinating topic to research, and I was lucky enough to attend a lecture by Dr Vidal on the Convivencia.

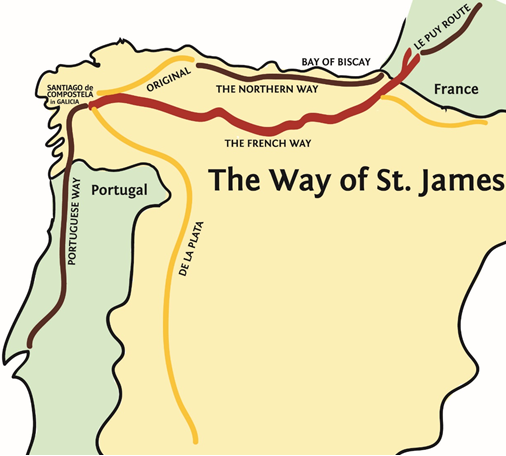

The Convivencia refers to a period of Spanish history in which all three Abrahamic religions (Christianity, Judaism, and Islam) cohabited together. Spreading mostly over a region referred to as “Al-Andalus”, (including modern day cities such as Seville, Cordoba, and Toledo in Spain) this 400-year period marked a distinct change in interfaith relationships and culture. Although the beginnings and ends of this history are filled with persecution and forced conversion, there existed a time in between, of centuries of peaceful coexistence and cooperation, with mutual cultural exchanges that benefited Muslims, Jews, and Christians.

Beginnings and interactions: The Convivencia began with Arab armies entering the Iberian Peninsula in 711 AD. The peninsula was previously held by Catholic Visigoths and was a region which, at the time, was very politically unstable. The region also contained many scattered Jewish communities who had arrived in the region roughly in the fourth century. Following the Muslim conquest of the peninsula, the majority of the Visigoths fled the region to Europe. However, the Christians who did not leave slowly adopted Muslim culture, including elements of the Arabic language. These Christians were referred to as Mozarabs and essentially adopted the customs and styles of Muslims, without converting. Over time relationships began to form between all three religious groups creating a unique and complex culture and society where all three functioned togther.

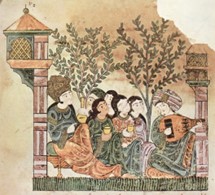

The migration of Christians and Jews into the thriving heart of Al-Andalus lead to exchanges in faith, language, and philosophy. As the communites lived in such proximity, interaction became unavoidable, leading to both inter-religious violence as well as peaceful cohabitation. There are records of Muslims allowing Christians to pray in their mosques, along with records of forced conversion and violence between the groups. These interfaith relationships did not exclude marriage or friendships, with several records of marriages and relationships between all faiths, even though it was forbidden. There are even records of shared business interactions where Jews and Muslims had partnerships in a store and divided the profits equally in accordance with their respective sabbath days (the profits of sales on Friday went only to the Jew and those of Saturday only to the Muslim).

Religious tolerance was probably at its highest in 912 AD when Abd Al-Rah Man III ruled over the Cordoba region. During his reign he was referred to as the “prince of all believers” and he encouraged reconcilition between all religious groups and brought about a period of relatively peaceful cohabitation.

Religious tolerance: Naturally, certain cities were more tolerant. Although these communities cohabited, they did not necessarily always exist in harmony. Many historians argue that the narrative of the Convivencia has shifted towards a utopian fallacy. Many records of this period give contradicting images of this period. Where there was harmony there was also mistrust between the other religions and converts. For example, a riot broke out against the Jews of Cordoba in March of 1135. ″because of a dead Muslim found among them.” Jewish houses were attacked and robbed, and a number of Jews were killed. Religious tolerance began to drastically decline towards the end of this period when Christian strongholds in the north began to slowly advance south. Christian – Muslim relationships specifically, were already strained due to religious differences, and laws were developed to segregate the communites further. In Valladolid, Muslims were required to wear long beards “as their law commands” to identify themselves as Muslim and no Christian woman was allowed to nurse a Jewish or Muslim child, and vice versa.

Downfall of the Convivencia: As the Christian kingdoms progressively expanded south taking over Muslim territory (in what is known as the “Reconquista”) the Muslim armies faced losses and retreated. When the Christians ultimately took power over the region, the Muslim and Jewish populations were faced with either forced conversion, exile, or death. While the Reconquista was ongoing, Muslims and Jews who came under Christian control were allowed to practise their religion to some degree, but this all ended in the late 15th century with the fall of Granada in 1492. In 1492, with the Alhambra decree, those Jews who had not converted to Catholicism were expelled and forced to abandon their homes, communites and businesses. With the expulsion of the Jews the Convivencia was over.

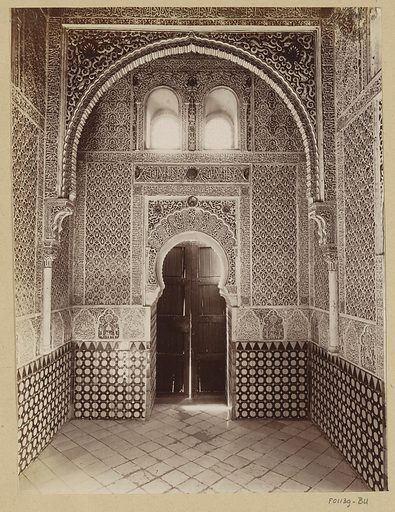

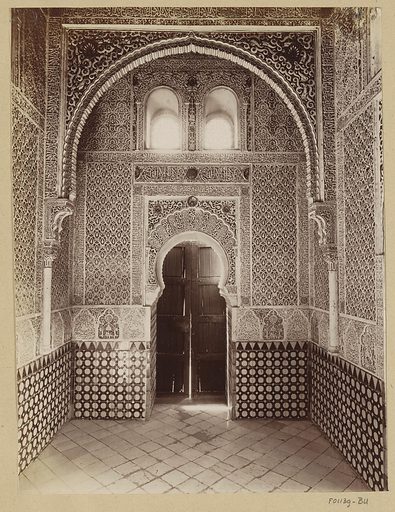

Prayer room in the Alhambra in Granada. Date: 1851 – c 1890. – Rijksmuseum

Impact and legacy: The Convivencia led to a great cumulation of knowledge from these respective communities, both linguistically and philosophically. The impact that it had on Spanish culture, language and architecture is often not very recognised. The Mozarab Christian population began to either speak Arabic or interchange it with Spanish during the Convivencia. The impact this had linguistically on Spanish can still be observed today with almost any words beginning with al- coming from Arabic roots e.g., Algodón (cotton) coming from the Arabic word Al-qutn. As a Spanish student it was very interesting to learn the linguistic roots in the language that can be traced back to this specific period. I also noticed that several common Spanish words come from Arabic, for example barrio (neighbourhood) comes from the Arabic word barrī , and the Spanish ojalá (I hope/maybe) comes from the Arabic inshallah. There are many other examples of this. Interestingly Spanish also influenced Hebrew which was the language spoken by the Jewish population in Spain at that time; the language Ladino was a Judeo-Spanish language which was entirely developed by Sephardic Jews who lived in the peninsula during this period and is still spoken today by diaspora communities. In addition to the blending of languages the merging of cultures was reflected in other ways. For example, Spanish Christians began to mirror Islamic geometric patterns, ornamental metals, and brick work. Some of these features are still present in the current Spanish architecture. The Muslim population also brought with them crops such as silk, cotton and satin leading to a very successful textiles industry within the region. Along with this the Arabs introduced the Arabic number system which compared to its roman counterpart included the number zero.

Conclusion: Sadly, due to the largely violent end of this period and the general resistance to Islam and Judaism from the newly Catholic country the existence and impact of their cultural, architectural and linguistic contributions from these groups were slowly and deliberately forgotten. The expulsion of the Jewish people meant that a Jewish presence in the region did not return for hundreds of years and the communities who converted to Christianity were constantly under the gaze of the Spanish inquisition. While elements of Muslim and Jewish culture remained, it largely evolved and assimilated into Spanish culture leaving only remnants behind. Overall, this topic has given me a greater understanding of Spanish culture and its history as well as giving me a deeper understanding of the Spanish language.

I gathered most of my information from articles such as Convivencia: Christians, Jews, and Muslims in Medieval Spain by By Lindsey Marie Vaughanm and Convivencia in Islamic Spain by Sarah-Mae Thomas as well as the talk I attended by Dr Vidal from Queen Mary University of London in April 2022.