Written by: Shreya Gupta

Until recently, China was the world’s most populous country with around 1.4 billion people, equivalent to a staggering 17.72% of the total world population. Yet, an irreversible population decline in China has led to India overtaking it as the world’s most populous country. Reasons for this mainly centre around the transition of China’s traditional centrally planned economy to a mixed economy, allowing for greater freedom from the state in many industries. This has allowed for China to become an internationally competitive country, with employment opportunities for men and women that has resulted in households no longer feeling obligated to have children. In fact, between 2019 and 2021, large Chinese provinces and cities have seen huge drops in birth rates, largely due to China’s economic boom. China’s urbanisation has also shown a change of view in a woman’s “purpose” and “role” in the household, particularly in rural areas. Chinese traditions that were once focussed on women being responsible for all domestic duties and having children, rather than aspiring to obtain a future career, have given way to greater emphasis on gender equality, especially in education. These progressive values have encouraged women to work rather than settling down and is leading to a view that marriage and birth are barriers to freedom.

However, the one-child policy implemented from 1980 to 2016 comes to mind as the most significant and impactful cause for this population change. Economic pressures and food insecurity during this period meant that Deng Xiaoping had to introduce this measure for the welfare of society. But many economists argue that, whilst this may have reduced short-term economic pressures, the policy is quite detrimental to China’s future economy. Predictions that China will surpass USA’s GDP in 2041 are now projected to be in danger due to its rapidly ageing population. One would never link a population shortage to such a populous country, but this can be seen in its shrinking labour force and consequent decrease in productivity levels. As an export-led economy, this could potentially have devastating consequences to both China’s domestic economy as well as global markets. China’s influence on the international stage is greatly threatened by its elderly demographic – by 2040, people 60 years or older will make up 28% of the population.

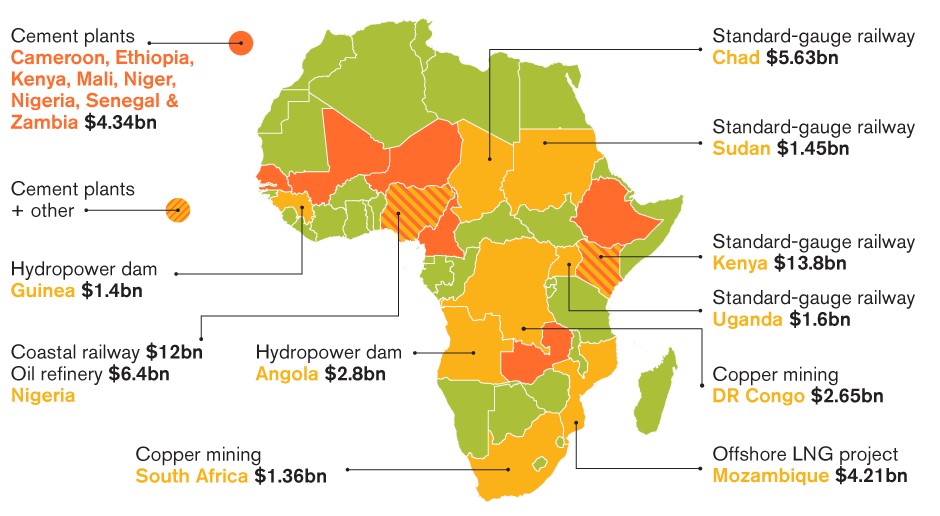

From a global perspective, this can potentially threaten many developing countries that rely on Chinese aid and investment. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has put 150 countries under its influence, which has undermined US influence as a major creditor across the world, particularly in Asia and Africa. Whether this is through the Belt and Road Initiative which is specifically a global infrastructure development project, or bilateral agreements, such as with Libya or Tanzania, China has transformed into the largest investor in the world. Therefore, population decline can have harmful effects in countries that have deep economic ties with China, particularly when major investments in developing countries are at stake. Sub-Saharan Africa is especially vulnerable to China’s economic slowdown – IMF (International Monetary Fund) shows how a 1% decrease in China’s growth rate can reduce growth in sub-Saharan Africa by 0.25%. We’ve already seen Chinese loans fall in this region since 2017. Lower investment and aid are bound to increase poverty with lower employment, living standards and development in general.

One can put a positive spin on this by arguing that a decline in Chinese influence on developing countries provides governments a perfect opportunity to escape from this “dependency culture.” Reports offer evidence that China’s investments are targeted at not improving conditions in countries, but rather exploiting Africa’s abundant natural resources. Geopolitically, this is a strategic move by China to improve their own economic growth and therefore dominance in the world, as well as compete with US influence and capitalist interests. Therefore, lower levels of Chinese commitments in African countries will allow them to become more self-sufficient or rely on other

countries such as the USA, improve competitiveness, and perhaps diversify their own exports for faster growth.

It is fair to say that this is a pivotal moment in global geopolitics and will have a significant impact on the shift in power dynamics between continents and nations; this will certainly be closely monitored by all countries as well as global institutions, such as the World Bank.

With its many uses – from industrial to home use, packaging, toys and clothes, its durability, light weight and low cost – plastics make economic sense and are in many ways ideal for 21st century living. But we are now all much more aware of the time – up to 1000 years – that plastics take to break down, when put into landfill. An estimated 3 million tonnes of plastic end up in the ocean each year. Alongside the life span factor, the raw material for traditional plastics – commonly from non-renewable sources such as oil – bring questions of sustainability. Acting on this, companies have looked for biomass (wheat, corn, sugar cane, sugar beet, potatoes and other plants) to turn into plastics. Thus, bioplastics have been created. A positive development, we might all agree.

With its many uses – from industrial to home use, packaging, toys and clothes, its durability, light weight and low cost – plastics make economic sense and are in many ways ideal for 21st century living. But we are now all much more aware of the time – up to 1000 years – that plastics take to break down, when put into landfill. An estimated 3 million tonnes of plastic end up in the ocean each year. Alongside the life span factor, the raw material for traditional plastics – commonly from non-renewable sources such as oil – bring questions of sustainability. Acting on this, companies have looked for biomass (wheat, corn, sugar cane, sugar beet, potatoes and other plants) to turn into plastics. Thus, bioplastics have been created. A positive development, we might all agree. What CocaCola want you to do is to recycle your PlantBottle in the correct facility. In keeping the bioplastic of the bottles in use, they are promoting the circular economy that is becoming much more of a consideration for anyone in the manufacturing process. The problem, of course, is the human factor: how can you ensure the correct separation of materials to recycle efficiently and without contamination? If the separation does not work, one type of plastic can easily be mixed into another type and thus contaminate a batch of recycled product. This batch is then not able to be used in certain situations or at all due to the change in properties.

What CocaCola want you to do is to recycle your PlantBottle in the correct facility. In keeping the bioplastic of the bottles in use, they are promoting the circular economy that is becoming much more of a consideration for anyone in the manufacturing process. The problem, of course, is the human factor: how can you ensure the correct separation of materials to recycle efficiently and without contamination? If the separation does not work, one type of plastic can easily be mixed into another type and thus contaminate a batch of recycled product. This batch is then not able to be used in certain situations or at all due to the change in properties.

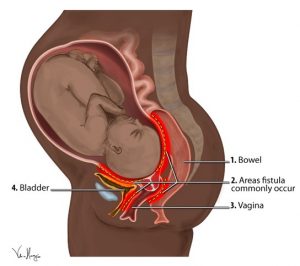

Days of unrelieved labour creates compression and cuts off both blood supplies to the baby and the mother’s internal soft tissue, causing both to die. The dead tissue results in holes (fistulas) in the walls separating the woman’s reproductive and excretory systems.

Days of unrelieved labour creates compression and cuts off both blood supplies to the baby and the mother’s internal soft tissue, causing both to die. The dead tissue results in holes (fistulas) in the walls separating the woman’s reproductive and excretory systems.

The Sinharaja Forest Reserve is a national park and a biodiversity hotspot in the southwest of Sri Lanka. It has been designated a Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site by UNESCO. There are 211 woody trees and lianas so far identified in the reserve, 66% of which are endemic, 20 of Sri Lanka’s 26 endemic birds are found here as well as half of Sri Lanka’s endemic mammals and butterflies.

The Sinharaja Forest Reserve is a national park and a biodiversity hotspot in the southwest of Sri Lanka. It has been designated a Biosphere Reserve and World Heritage Site by UNESCO. There are 211 woody trees and lianas so far identified in the reserve, 66% of which are endemic, 20 of Sri Lanka’s 26 endemic birds are found here as well as half of Sri Lanka’s endemic mammals and butterflies. This Eco lodge encourages ecotourism.

This Eco lodge encourages ecotourism.