Written by: Phoebe Clayton

If you’ve spent enough time around me, you will have heard about the infamous 18th century dress, the so called ‘Chemise de la Reine’. To explain, a ‘chemise’ was a women’s undergarment, worn directly against the skin under a set of stays or as a nightgown, and usually made of fine white material. In 1783, Marie Antoinette (the ‘reine’ at that time) was painted wearing a dress which loosely resembled a ‘chemise’, displayed at the Salon de Paris in the Louvre. The gown sparked outrage due to its perceived informality and nonconformity with the highly structured aesthetic of traditional court gowns. It was unlike anything worn by French aristocracy before. But although named after the queen, the ‘Chemise de la Reine’ was not invented by Marie Antoinette. So, where did it come from?

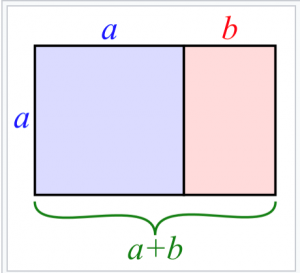

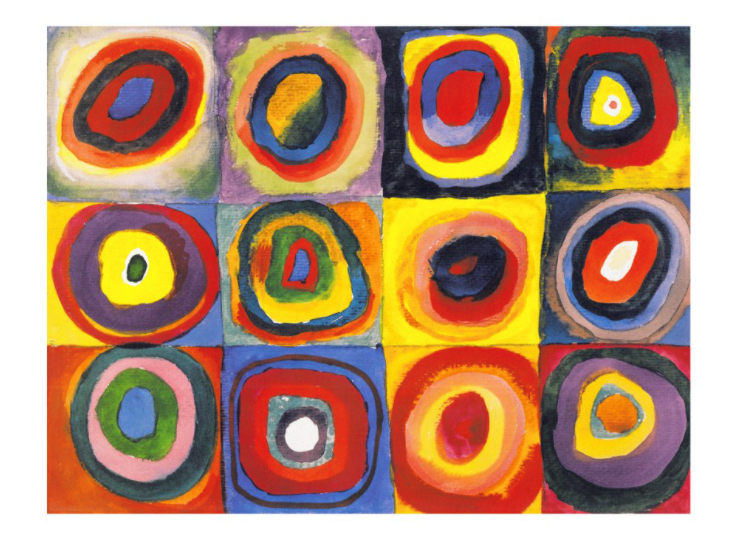

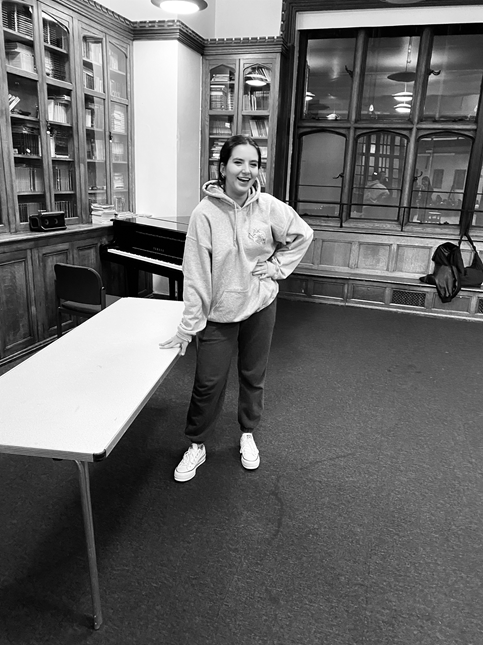

Marie Antoinette en gaulle, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, 1783

The dress itself was made by her tailor, Rose Bertin, who adapted it based on clothes of white women in the West Indies, who had themselves appropriated the style from women of colour. The gown first came Paris in the form of a fashion plate published in 1779 depicting a women dressed ‘in the Creole style’. In fact, Antoinette herself refers to the gown as ‘Le Robe a la Creole’ in her diaries, suggesting a direct awareness of the colonial cultural origins of the dress.

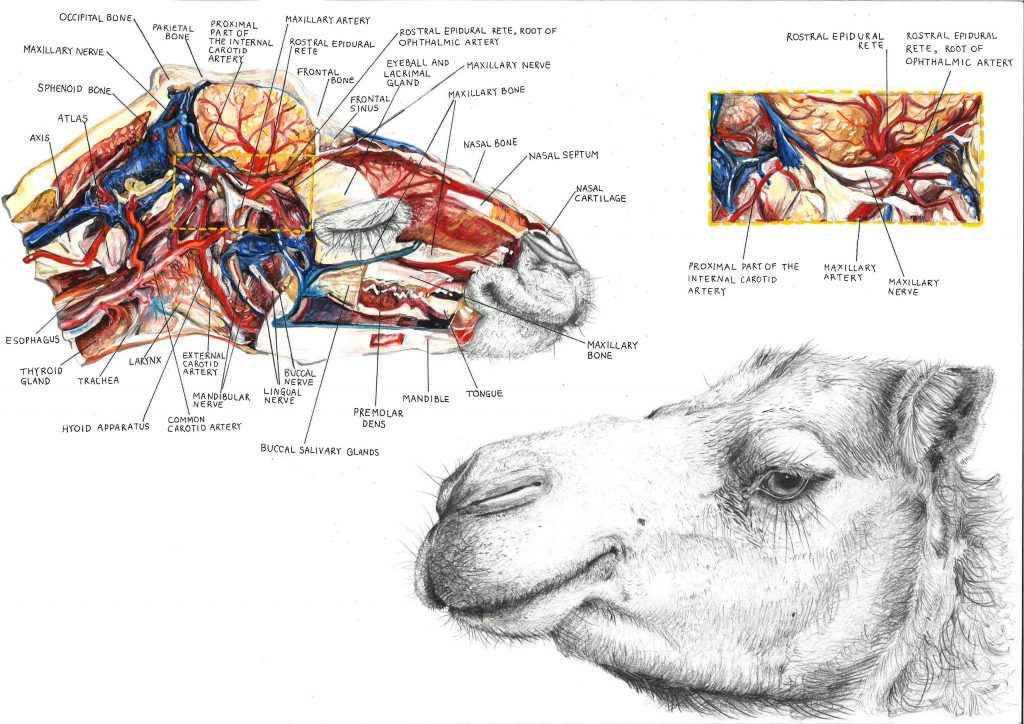

The term ‘creole’ refers to ‘a person of mixed European and black descent, especially in the Caribbean’, implying the inherently multi-racial context of the dress’ origins. Thus, the dress was likely first worn by women of colour, made of undyed madras material – which already widely imported to both West Africa and the Caribbean at this time, as it was light and well-suited to hot or tropical climates. Two black women wearing similar white, flouncy gowns strikingly reminiscent of Antoinette’s ‘chemise’ are featured in a Brunias painting from 1770, and two other women of colour wearing the style are featured in similar painting of his from c.1780. Agostino Brunias, who was active in documenting colonial life in the Caribbean in his art, later depicts white, black and creole women all wearing similar loose, white, chemise-type dresses in his ‘Linen Market’, 1780.

Free West Indian Dominicans, Agostino Brunias, c.1770

It is clear from this series of visual evidence the gradual appropriation of ‘chemise’ style dresses by white women – likely for reasons of practicality as well as a more hostile jealousy towards black beauty and style. One can ascertain the latter from the increasing sumptuary laws (legislation controlling what certain demographics can or can’t wear) that enslaved and formerly enslaved people were subject to during this period in the Caribbean, suggesting that white colonist elites felt threatened by the fashion and expression of black communities and thus restricted it to the best of their ability.

However, while the adoption of ‘chemise’-type gowns by white women in the West Indies is a clear appropriation and attempt at mimicry of black fashion, Marie Antoinette’s motivations in donning the style are harder to discern. Although she shows clear awareness of the apparent ‘creole’ origins of the dress, general contemporary and modern census is that the queen was instead imitating a romanticised, pastoral, ‘shepherdess’ style, trying to emulate the perceived idyllic simplicity of a rural lifestyle. For reasons obvious to anyone with a passing awareness of 18th century France (think: economic crisis, famine and widespread destitution), such an imitation was met with decidedly ill reception and offence caused at the queen’s ignorant naiveté and apathy to the struggles of her own subjects.

After Antoinette was painted in her controversial rendition of the gown, it immediately became known as the ‘Chemise de la Reine’ and quickly caught on, gaining popularity amongst upper class women in France, England and wider Europe. The style caused a seismic shift in 18th century women’s clothing and, as the 1790’s dawned, sent fashion careening straight into the regency period. The white, gauzy fabric finely gathered beneath the bust, puffed sleeves, square neckline and simple skirt all became foundational staples of women’s fashion for the next 40 years. It had a truly transformative impact. And, although the gown travelled far from its birthplace of the Caribbean, it is important to acknowledge the black and Creole origins of the Chemise de la Reine and recognise their monumental influence on an entire century of Western women’s fashion.

Bibliography

DuPlessis, R. (2019). Sartorial Sorting In The Colonial Caribbean And North America. The Right To Dress: Sumptuary Laws In A Global Perspective, c.1200–1800,

[online]

pp.346–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108567541.014.

Halbert, P. (2018). Creole Comforts and French Connections: A Case Study in Caribbean Dress. [online] The Junto. Available at: https://earlyamericanists.com/2018/09/11/creole-comforts-and-french-connections-a-case-study-in-caribbean-dress/#_ftn1.

Peterson, J. (2020). Robe en Chemise or Chemise a la Reine – Pattern 133. [online] Laughing Moon Merc. Available at: https://www.laughingmoonmercantile.com/post/robe-en-chemise-or-chemise-a-la-reine.

Square, J.M. (2021). Culture, Power, and the Appropriation of Creolized Aesthetics in the Revolutionary French Atlantic | Small Axe Project. [online] smallaxe.net. Available at: https://smallaxe.net/sxsalon/discussions/culture-power-and-appropriation-creolized-aesthetics-revolutionary-french.

Van Cleave, K. (2021). On the Origins of the Chemise à la Reine. [online] Démodé Couture. Available at: http://demodecouture.com/on-the-origins-of-the-chemise-a-la-reine/.

Whitehead, S. (2021). À la Creole, en chemise, en gaulle: Marie Antoinette and the dress that sparked a revolution.

[online]

Retrospect Journal. Available at: https://retrospectjournal.com/2021/05/09/a-la-creole-en-chemise-en-gaulle-marie-antoinette-and-the-dress-that-sparked-a-revolution/.