You might like to visit the Wellcome Collection which is a free museum and library with many different events that create opportunities for people to think deeply about connections between science, medicine, life and art.

You might like to visit the Wellcome Collection which is a free museum and library with many different events that create opportunities for people to think deeply about connections between science, medicine, life and art.

Rachel Evans, Director of Digital Learning and Innovation at WHS, looks at the links between Art and Artificial Intelligence, investigating how new technology is innovating the discipline.

What is art? We might have trouble answering that question: asking whether a machine can create art takes the discussion in a new direction.

Memo Akten is an artist based at Goldsmith’s, University of London where much exciting work is taking place around the intersection of artificial intelligence and creative arts.

Akten’s work Learning to see was created by first showing a neutral network tens of thousands of images of works of art from the Google Arts Project. The machine then ‘watches’ a webcam, under which objects or other images are placed, and uses its ‘knowledge’ to create new images of its own. This still is from the film Gloomy Sunday. Was it ‘thinking’ of Strindberg’s seascape?

I have been fascinated by this artwork since I first saw it and have watched it many times. The changing image is mesmerising as the machine presents, develops and alters its output in response to the input. It draws me in, not only as a visual experience, but for the complex response it provokes as I think about what I am seeing.

Akten describes the work as:

An artificial neural network making predictions on live webcam input, trying to make sense of what it sees, in context of what it’s seen before.

It can see only what it already knows, just like us.

In 1972 the critic John Berger used the exciting medium of colour television to present a radical approach to art criticism, Ways of Seeing, which was then published as an affordable Penguin paperback. In the opening essay of the book he wrote “Every image embodies a way of seeing. […] The photographer’s way of seeing is reflected in his choice of subject. […] Yet, although every image embodies a way of seeing, our perception or appreciation of an image also depends on our own way of seeing.” When Akten writes that the machine “can see only what it already knows, just like us” he approaches the idea that the response of the neural network is human-like in its desire to find meaning and context, just as we attempt to find an image which we can recognise in the work it creates.

If the artist is choosing the subject, but the machine transforms what it sees into ‘art’, is the machine ‘seeing’? Or are we wholly creating the work in our response to it and the work is close to random – a machine-generated response to a stimulus not unlike a human splattering paint?

Jackson Pollock wrote “When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing. It is only after a sort of ‘get acquainted’ period that I see what I have been about. I have no fear of making changes, destroying the image, etc., because the painting has a life of its own.” Is the neural network performing this role here for the artist, of distancing during the creative process, of letting the ideas flow, to be considered afterwards?

Is the artist the sole creator, in that he has created the machine? That might be the case at the moment, with the current technology, but interestingly Akten refers to himself as “exploring collaborative co-creativity between humans and machines”.

I find this fascinating and it raises more questions than I can answer: it leaves me wanting to know more. It has prompted me to delve back into my own knowledge and understanding of art history and criticism to make connections that will help me respond. In short – encountering this work has caused me to think and learn.

In the current discussions in the media and in education around artificial intelligence we tend to focus on the extremes of the debate in a non-specific way – with the alarmist ‘the robots will take our jobs’ at one end and the utopian ‘AI will solve healthcare’ at the other. A focus for innovation at WHS this year is to open up a discussion about artificial intelligence, but this discussion needs to be detailed and rich in content if it’s going to lead to understanding. We want the students to understand this technology which will impact on their lives: as staff, we want to contribute to the landscape of knowledge and action around AI in education to ensure that the solutions which will arrive on the market will be fair, free of bias and promote equality. Although a work of art may seem an unusual place to start, the complex ideas it prompts may set us on the right path to discuss the topic in a way which is rigorous and thoughtful.

So – let the discussion begin.

Rebecca Owens, Head of Art at Wimbledon High School

Printmaking has always been one of the things I enjoyed the most when I studied at Camberwell School of Art. So, when I started at Wimbledon High School I decided to introduce as many of the techniques as possible. There is something magical about the processes as the results are always a bit unexpected. Rather like a good gardener will learn some strategies to help achieve the results she wants, and tame nature in the garden, she will inevitably have moments of surprise. The same is true of printmaking. Whilst you can learn the techniques and become more familiar with the results, there is often a WOW moment, and an unexpected outcome. As the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig-Kirchner said:

‘The technical procedures doubtless release energies in the artist that remain unused in the much more lightweight processes of drawing or painting’ (remark on printmaking).

In this article I have outlined why I think printmaking is important, what the different types of printmaking are and how we use printmaking at Wimbledon High School.

Printmaking

Printmaking revolutionised how images were disseminated, with the first publication of books and the subsequent development of printed images in the mid fourteenth century enabling more people to own images, and for these images to be moved around. The letter press or moveable type, first mentioned in 1439, was designed by Johannes Gutenberg. The increased production of books over the next few decades meant that the price of paper dropped, and as a result, that artists had cheaper access to the media. Artists started to work in different ways, with woodcuts, wood engravings or engravings on metal often used to create the printed images found in books. In this respect, printmaking allowed the artist to be more egalitarian, and reach a much wider audience, as each print could be sold for less money than the original.

Why use printmaking in school

The process of printmaking allows students to work and think in a completely different way, as printed outcomes often have unexpected results. This characteristic of the process allows students to experiment liberally with the further development of their images. Indeed, the disconnection between a student’s expected outcome, and the physical reality of their print is part of the pleasure of printing, it liberates the artist and helps them to investigate unexpected and exciting ways of working. Once the screen or block has been created, the student can explore overprinting onto different surfaces, try differing colours schemes or experiment with making the two-dimensional print into a three-dimensional piece. Some students thrive and gain in confidence when they are constrained by some conventions to react against, or rules to break, as David Hockney states “limitations in art have never been a hindrance. I think they are a stimulant”.

There are many advantages to introducing the different skill set required for Printmaking, but one important reason to me is that it allows Art to be rewarding to a greater range of people. The boundaries in the technique encourage creativity.

“Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

― Pablo Picasso

Drypoint

A drypoint needle is used to scratch into the plate, which may be metal or plastic. Ink is then rubbed into the plate. The paper is dampened before printing, so that as it passes between the two rollers, the ink is lifted out from the scratches.

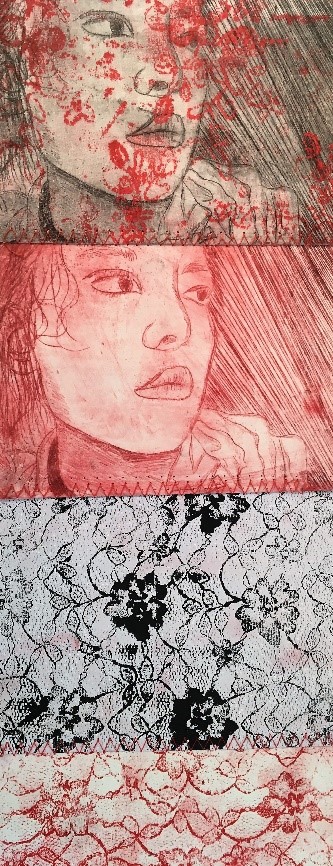

These prints are based on portrait images that the students took of themselves, their friends and family. The theme was reflections and distortions, where the students explored different reflective surfaces and other ways of distorting their images. The prints were created using an etching needle and a plastic plate. Professionals would use metal plates as they are more durable and so a bigger edition can be created.

Ruby (Year 10)

Ruby (Year 10)

Zara (Year 10)

Zara (Year 10)

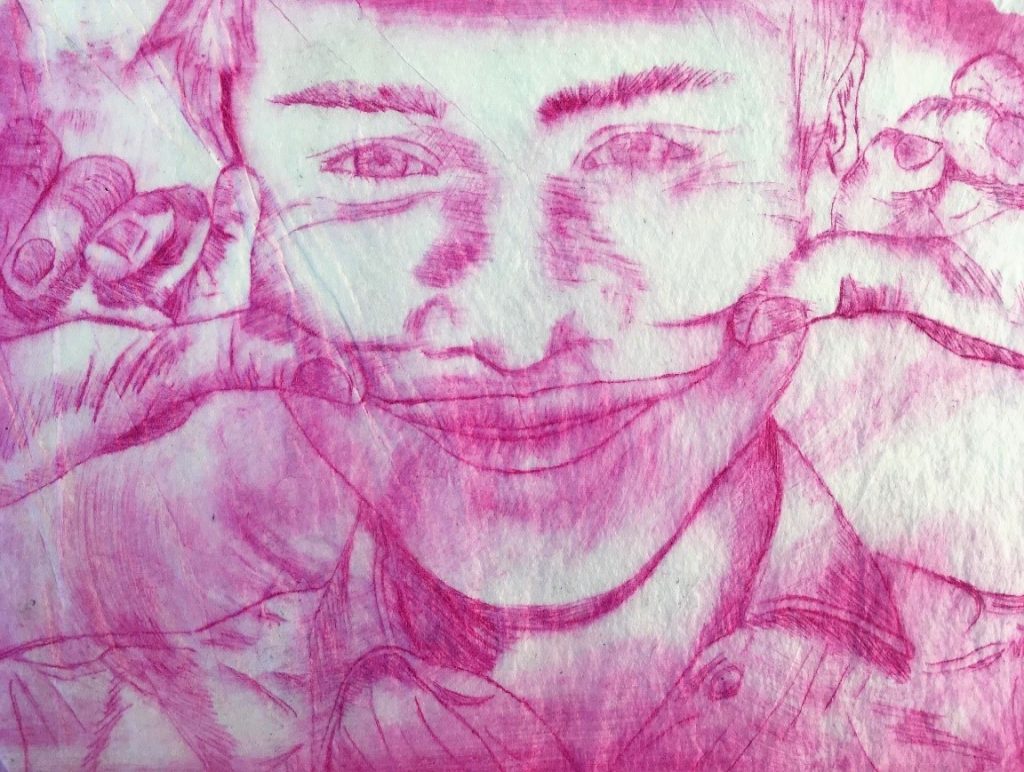

Issie (Year 13)

Issie (Year 13)

Using a combination of etchings, rubbings of textured surfaces Issie created the laminates from which this installation was created. The images explored the contrasting shapes found in Kew gardens.

Etching

Plates are coated with different grounds, and the ground is then removed using the etching needles. The plates are placed in acid, where the acid etches into the metal, creating areas which will hold the ink during the printing process. This process is often combined with aquatint which achieves the graduated tones, as evident in the work of Norman Ackroyd. The artists’ beguiling, monochromatic works of the British Isles achieve a soft, seemingly watercolour-like effect through a combination of etching and aquatint processes. Explore his work here.

Woodcut printing

This technique uses blocks of wood where the grain is parallel to the printing surface. This allows for working on a bigger scale than wood engraving, and as the cuts follow the grain there can be some slipping as the design is cut. The grain of the wood is also evident in the print, with artists like Nash Gill using this characteristic of the process to add texture and interest to their compositions. Ink is applied using rollers and the lines cut remain the colour of the paper. The work of Kathe Kollwitz shows how the simplicity of a print can be used to create images which elicit an emotional response. She used her work to comment on society at the time focussing on poverty and loneliness. See her work here.

Wood engraving

This uses the end grain of wood, often box or lemon wood, as the grain is fine and consistent. As these woods are slow growing, the blocks available are smaller. The cutting process is very hard, requiring sharp tools, but there is less slipping as the tools are cutting across even grain. Ink is applied using rollers and the lines cut remain the colour of the paper. John Lawrence delicate and fine wood engravings have been used as illustrations in numerous fine art publications and books. See his work here.

Lino printing

Using linoleum to create the block. Lino is hessian backed and made from cork. It is easier to cut than wood prints, but has a similar bold effect. The lines cut do not hold the ink as the ink is applied using rollers to the surface of the block. Grayson Perry uses large scale lino prints to create his exciting images which present his critique and commentary on contemporary life. View his work here.

Year 7 Lino prints

Lino prints, akin to wood engravings, require the artist to work in reverse as the areas which are cut away do not hold the ink. Whereas lines are normally drawn in a dark colour on a light background, when working on a lino design it is necessary to reverse that process. For that reason, it is helpful when designing a lino print to make a plan using white chalk on black paper. As an introduction to lino printing Year 7 are shown how to work in this way. It has the additional benefit that white chalk is relatively tricky to create very fine marks with, so it encourages everyone to be bolder. Indeed this is also beneficial as it is difficult to cut out shapes which are too intricate.

Shanalia (Year 7)

Shanalia (Year 7)

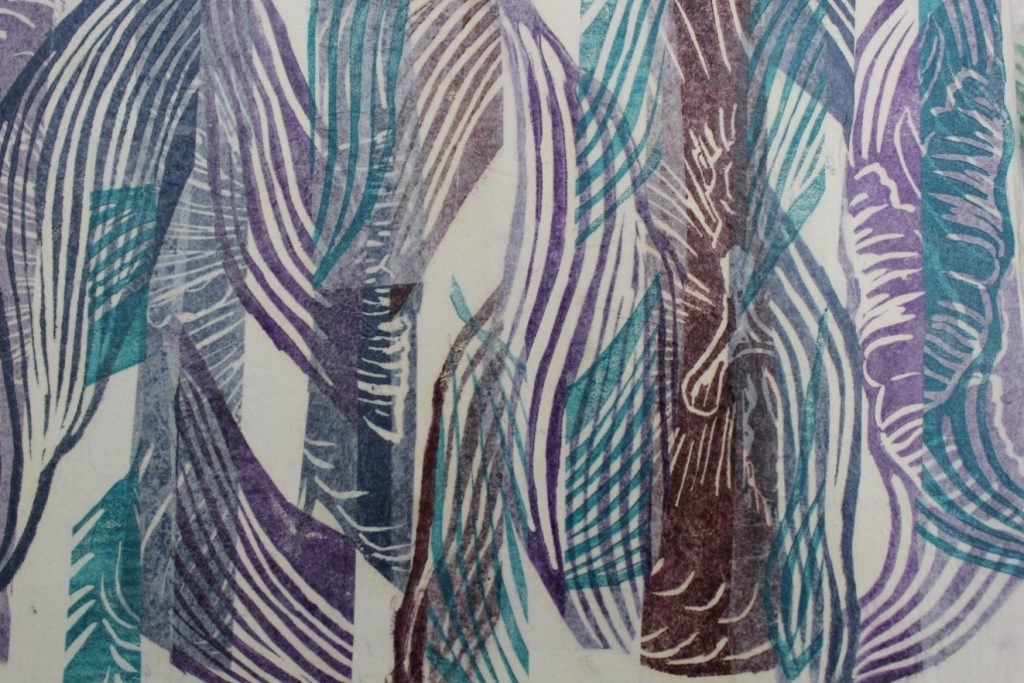

Tulip 1 by Rebecca Owens

I made this piece using Linocut prints on white tissue paper, collaged together. The rhythmic patterns in organic forms have always inspired my work. ‘Tulips 2’ aims to contrast the fluid shapes found in tulip flowers and leaves, with the geometric composition of the collage. I am fascinated by the delicacy and semi-transparent nature of the thin paper. The way the overlaying of the bold Lino prints creates unexpected focal points and a subtle range of colours, is also intriguing.

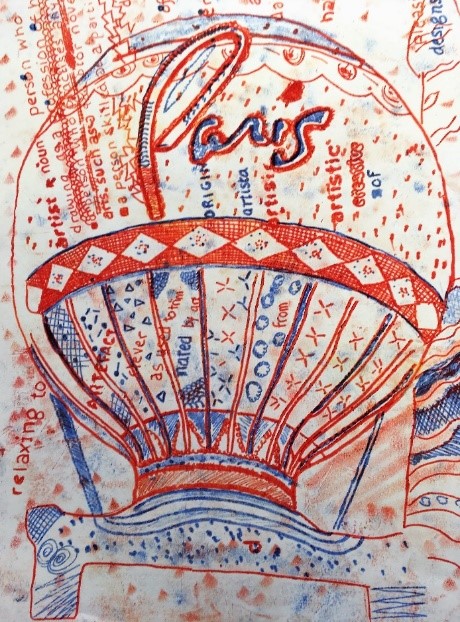

Kate (Year 9)

On the theme of Text in the Environment students in Year 9 took some amazing reference photographs from which to develop their ideas. They used these to create their monotype prints. As the name would suggest, these are one off prints, where the ink is rolled out or laid onto a board, paper or other flat surface and a second sheet of paper is laid onto the inked area. By drawing on the back of the paper the ink is transferred. It has the same wonderful sense of excitement and often gives an exciting moment in lessons, when students reveal their prints.

Eryngium – Monotype print by Rebecca Owens

Using a silk or synthetic mesh stretched over a screen. The ink is then pressed through the screen using squeegees. Stencils can by created for the screen using papercuts, by photographically transferring images onto the screen using light sensitive materials or by blocking the screen using stoppers. This media was used by artists such as Rauschenberg and Warhol in contrasting ways. Recently Ciara Phillips immersive installations created with prints engaged and intrigued the viewers, through her exploration of the process of printmaking. See her discuss her work here.

Year 11 and 13 mixed media work including prints.

These images demonstrate the exciting ways in which the students have experimented with these techniques.

Ava (created when she was in year 11)

Her screen prints on the theme of natural forms were folded to create this sculpture.

Lucy (Year 11)

In this piece she has combined pen drawing with screen printing.

Imogen (Year 13)

This large scale mixed- media piece contains etchings and screen prints which she used to create this sculptural piece.

Lithography

Using a stone or metal plate which has been sensitised to any greasy material, drawing is added using wax or chinagraph pencils. The plate is then brushed with liquid etch and coated with gum Arabic. The second stage of the process sees the black disappearing and leaving a waxy shadow. These will be the areas that hold the ink when printing. With lithography the plate has to be wet before ink is applied and kept damp.

Conclusion

Printmaking allows students flexibility and freedom to experiment. The contemporary artists included earlier in this article use printmaking to tackle important and universal themes through their printmaking. They are evidence that printmaking today is used by artists in increasingly diverse ways, to create artworks relevant to contemporary society.

Creativity allows students to develop different ways of thinking and as Art never has a right or wrong answer, there is a different thought process involved in solving a visual conundrum. Printmaking feeds into student’s visual vocabulary, allowing them the ability to express their ideas in a range of sophisticated ways, and helping them to express their thoughts and ideas..

“Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.”

Pablo Picasso

Bibliography

A History of pictures by David Hockney and Martin Gayford – Thames and Hudson

Art The definitive visual guide by Andrew Graham-Dixon – Dorling Kindersley

The Encyclopaedia of Printmaking Techniques by Judy Martin – Quarto publishing

Daisy (Y12) explores the significance of the castles that are dotted all over the British Isles, arguing that we should look beyond their architectural genius to study the stories behind them.

Castles are undoubtedly the most important architectural legacy of the Middle Ages. In terms of scale and sheer number, they undermine every other form of ancient monument and dominate the British landscape. What’s more, the public has an enduring love affair with these great buildings since they play an intrinsic role in our heritage and culture, meaning that over 50 million people pay a visit to a British castle each year.

Arundel Castle, West Sussex

The period between the Normans landing at Pevensey in 1066 and that famous day in 1485 when Richard III lost his horse and his head at Bosworth (consequently ushering the Tudors and the Early Modern period in to England), marks a rare flowering of British construction. Whilst the idea of “fitness for purpose” was an important aspect of medieval architecture, the great castles of the era demonstrate that buildings had both practical and symbolic use.

One of the most iconic forms of medieval castle, was that of the Motte and Bailey which ultimately came hand in hand with the Norman conquest of 1066. The Bayeux Tapestry eloquently depicts the Norman adventurers landing in Pevensey and hurrying to occupy nearby Hastings. The men paused on the Sussex coast and are said to have indulged in an elaborate meal whereby they discussed their plans for occupying the highly contested country. The caption of the Tapestry notes “This man orders a castle to be dug at Hastings”, which is followed by a rich scene illustrating of a group of men clutching picks and shovels heading to start their mission- castles were the Normans first port of call. In the years that followed, castle-building was an intense and penetrating campaign, with one Anglo-Saxon Chronicler stating that the Normans “built castles far and wide throughout the land, oppressing the unhappy people, and things went from ever bad to worse”. It was vital for William to establish royal authority over his newly conquered lands, and thus the country saw the mass erection of potentially more than 1,000 Motte and Bailey castles. With these buildings, speed was of the essence, and so the base, or Bailey, was made of wood, while the Keep (which sat on the top of the Motte) was relatively small and made of stone.

A drawing displaying a Motte and Bailey Castle.

Despite the fact that these castles obviously served a defensive purpose, with the elevation from the Motte providing the Norman noble with a panoramic view of the surrounding countryside, their symbolic purpose was arguably of greater significance. The erection of such a large number of castles set out to alter the geopolitical landscape of the country for ever and made sure that the Norman presence would be felt and respected. Figuratively, the raised Keep acted as a physical manifestation of the Norman’s dominance over the Anglo-Saxons with the upwards gradient effortlessly representing the authoritative function and higher superiority of the Lord, which was the fundamental aspect of the feudal system. Additionally, as many academics tend to emphasise, the fact that they were often located in order to command road and river routes for defensive purposes meant that their possessors were also well placed to control trade, and thus could both exploit and protect mercantile traffic.

Another key development in castle building occurred approximately 200 years after the Battle of Hastings, during the reign of Henry II. Prior to Henry’s accession, England had been burdened by civil war and a period known as the “anarchy” under his predecessor, King Stephen. Taking advantage of the confusion and lawlessness displayed throughout Stephen’s reign, the barons had become fiercely independent. They had not only issued their own coinage but also built a significant number of adulterine castles and had unlawfully adopted a large sum of the royal demesne. As a result, in order to establish royal authority, Henry set about demolishing these illegal castles en-masse, on which he expended some £21,500, and further highlighted his supremacy. Thus, as seen under the Normans, castles were again used as a means of establishing royal authority. From here the British landscape was significantly altered for a second time, which, in a period lacking efficient communication and technologies would have been a highly visible emblematic change impacting all members of society from the richest of the gentry to the everyday medieval peasant.

As a result, whilst is it important to appreciate the architectural styles and physical construction of medieval castles, I believe it is vital to acknowledge their symbolic nature, and appreciate how through the introduction of such fortresses, peoples’ lives would change forever.

Follow @History_WHS on Twitter.

Richard Bristow, Director of Music at WHS, looks at recent developments in the creative curriculum.

|

‘Creative industries worth almost £10 million an hour to economy’ Dept. of Digital, Culture, Media & Sport, January 2016

‘Creative industries grow twice as fast as UK economy in 2015-16, making up 5.3% of the economy’ Economic Estimates for 2016 Report

‘The government is aiming for 90% of Year 10 pupils to be studying the EBacc…by 2025’ Telegraph April 2018

‘Arts education should be the entitlement of every child’ Nick Gibb, Schools Minister, April 2018

|

‘Music could “face extinction” in secondary schools in England, researchers have warned’ BBC, March 2017

“A combination of cuts to school budgets and the consequential loss of specialist teachers has created a skills loss” Prof Colin Lawson, Director of RCM, March 2018

‘How to improve the school results: not extra maths but music, and loads of it’ Guardian, October 2017

‘Axe looms for county music service: 7000 school instrumental lessons impacted’ Sussex Express, April 2018

|

The news reports above pose a dilemma. On one hand, Creative Industries in the UK have had a celebrated few years, adding significant value to the UK economy; on the other, cuts to creative (and specifically Music) education in secondary schools in England paint a bleak picture of an emerging skills gap, threatening this very success.

| A recent BBC survey with data collected from over 1200 schools – some 40% of all secondary schools in England – revealed a damming 90% of schools have made cuts to staffing, resourcing or facilities to at least one creative arts subject over the last year. Music, Drama, Art and Design and Technology all find themselves squeezed because of a growing need to teach ‘academic’ subjects – a key feature of the new English Baccalaureate (or EBacc for short), which has become a compulsory part of state education in England. This division of academic and creative is a central problem in education. After all, we want creative solutions to scientific problems, and an academic approach to art allows for increased understanding. Yes, the Theory of Relativity is complex, but so is Schenkerian musical analysis. Why do we have to choose? Why can we not value both? |

90% of schools have made cuts to the creative arts over the last yearBBC Survey |

Introduced from 2010, the EBacc seeks to counter the fall in numbers of pupils studying foreign languages and sciences (see here) by measuring pupil progress in English, maths, the sciences, a language and either history or geography.

EBacc Subjects:

|

The Government originally set a target of 90% of Year 10 pupils studying the EBacc to be achieved by 2025. This however has recently been reduced to 75% in the latest Conservative manifesto – not to allow for a broadening of the EBacc subjects, but because there are not enough Modern Foreign Language teachers to allow the original target to be met. The cuts to language teaching are a little more established than the more recent cuts to creative subjects, showing the ‘boom and bust’ approach to education in the UK in the 21st Century (see here for more information on MFL provision).

|

However, despite the significant press coverage of schools closing their music departments (see here) and some schools even charging pupils to study Music at GCSE (see here) the data seems to show a mismatch. A New Schools Network report (which can be viewed here) analysing data for all state school GCSE entries between 2011/12 and 2015/16 actually shows a rise in the number of pupils sitting at least one creative subject at GCSE over the period and confirms that pupils who achieve the very best EBacc grades are likely to have also achieved well in a creative arts subject. However, it also shows other issues:

These points add to the confusion. If the picture is as positive as this report suggests, why are we seeing reports suggesting the ‘extinction’ of subjects like Music in state schools? If the picture is one where the evidence shows the EBacc has not declined the provision of arts education, why are Music departments and Music hubs closing? How can pupils access an arts curriculum if the department is not physically there?

Perhaps the biggest problem with the report is that it does not give data for individual subjects. It might show a rise for the pupils studying the creative arts, but it does not show a rise in all creative subjects. So whilst the numbers studying Art or Design and Technology (part of the STEAM initiative) might have risen sharply, this might be at the expense of Music or Drama, who might have seen a strong decline in education provision. This data is needed to truly understand the impact of the EBacc on individual creative subjects.

The NSN Arts Report also calls upon Art Providers to be more active in helping to engage pupils in the creative arts (see Kendall et al, The Longer-Term Impact of Creative Partnerships on the Attainment of Young People). This might be via art organisations setting up free schools, or more likely to encourage art organisations to engage with a cultural education programme with school pupils.

One such example is the Philharmonia Orchestra who have recently completed their Universe of Sound and 360 Experience Project. This exciting project uses virtual reality to film the Philharmonia Orchestra performing Holst’s The Planets allowing people to experience and learn more about the symphony orchestra. They have also commissioned new music by Joby Talbot to give a contemporary interpretation to writing music to represent time and space. I have been lucky enough to do some work on the education resources for this programme over the Easter break, and it is hoped that this experience can offer pupils, parents and teachers a way into linking Music to other STEAM subjects, rising cultural engagement and musical understanding. If you would like to learn more about the project, please visit here for more information.

If we are to view subjects by their perceived academic worth, then it can be useful to view how the subject has been taught through history. Whilst many would view Music as now being a creative (and not academic subject), it is important to remember that Music as an academic and theoretical subject was one of the Ancient Greek seven liberal arts and a part of the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy) which was taught after the trivium (grammar, logic and rhetoric). Rather than being marginalised as a non-academic subject, we should relish the fact that Music can and has informed scientific understanding throughout history. Practical study of Music is obviously a useful skill, but it is the academic and theoretical knowledge that comes from advanced study of the subject that can really inspire the very best musicians. Perhaps we should redefine STEAM to STEAMM – Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, Maths and Music.

Or maybe we should lose the hierarchy altogether; perhaps, instead of putting subjects against each other in some fruitless competition, we should value passion, enjoyment and the love of learning, seeing the subjects as having equal worth. As Ian McEwan states:

“Science, the humanities and the arts are all forms of investigation,

driven by curiosity and delight in discovery.

The child who flourishes in one should flourish in the others.

The best, the liveliest education, would nourish all three.”

Richard Bristow, 21st April 2018

Follow @Music_WHS on Twitter

What if we heard music and at the same time could see colours? What if we composed music to create colours? Louisa (Year 12) investigates synesthesia and musical composition.

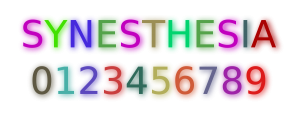

Synesthesia is the neurological condition where the stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in another. There are many different types, however common examples include grapheme-colour synesthesia where letters and numbers are seen as clearly coloured and chromesthesia where different musical keys, notes and timbres elicit specific colours and textures in one’s minds’ eye. For example, some synesthetes may clearly see the musical note F as blue or Wednesday as dark green or the number 6 as tasting of strawberries.

How some synesthetes may experience letters and numbers

Whilst some synesthetic associations are more common than others, it is possible for them to occur between any number of senses or cognitive pathways.

The definitive cause of synesthesia is not yet known, however most neuroscientists agree it is caused by excess interconnectivity between the visual cortex of the brain and the different sensory regions. It is estimated that around 1 in 2000 people experience true synesthesia and it is more common in women than men, however it may be more common as many who have it may not consider it a condition and leave it unreported.

One area in which there is a large concentration of synesthetes is in the arts; notable synasthetes include composers Olivier Messiaen, Franz Liszt and Jean Sibelius, Russian author Vladimir Nabokov, artists Vincent van Gogh and David Hockney, jazz legend Duke Ellington and actress Marilyn Monroe.

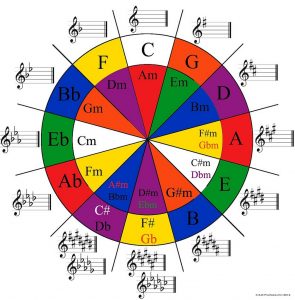

Composers who experienced chromesthesia (the type of synesthesia where musical keys and notes and sometimes intervals are associated with colours) often actively incorporated it into their works and in some cases made it central to their compositions.

How musical keys may be seen by people with chromesthesia

French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) was quoted as saying “I see colours when I hear sounds but I don’t see colours with my eyes. I see colours intellectually, in my head.” He said that if a particular sound complex was repeated an octave higher, the colour he saw persisted, but grew paler. If the octave was lowered the colour darkened. Only if the sound complex was transposed into a different pitch did the colour inside his head radically change.

For Messiaen, it was vital that performers and listeners of his music understood the colours he was portraying in his compositions and he did this by writing instructions in his scores. For example, pianists in the second movement (Vocalise) of his Quartet for the End of Time, written in a prisoner of war camp in 1940, are told to aim for “blue-orange” chords. Similarly, musicians playing ‘Couleurs de la cité céleste’ are instructed to conjure “yellow topaz” for one chord cluster and “bright green” for the next as well as many more examples.

Another composer who actively made use of his synesthesia is Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (1865-1957). Sibelius wrote that “music is for me like a beautiful mosaic which God has put together”. He said if he heard a violin playing a certain piece of music, he would see a corresponding colour such as colour of the sky at sunset in the summer. The colour would be uniquely specific and would only be triggered by a particular sound. This means many of his compositions have strong links to imagery experienced by Sibelius which may account for the strong emotional pulse that can be heard throughout his compositions.

Similarly, Franz Lizst (1811-1886) was known to use his synesthesia in his orchestral compositions, saying “O please, gentlemen, a little bluer, if you please! This tone type requires it!” or “That is a deep violet, please, depend on it! Not so rose!” Initially the orchestra believed Liszt was just joking before realising Lizst did in fact see colours for each tone and key.

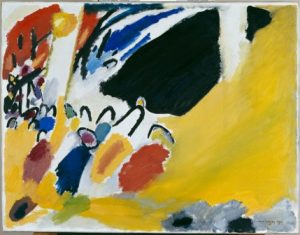

It can be difficult to understand the experiences of true synesthetes when not having the condition oneself, however this can be made easier by looking at the works of synesthetic artist Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), the first abstract painter. Instead of using his synesthesia to compose new music, he would create artwork based on the music he heard.

Kandinsky discovered his synesthesia at a performance of Wagner’s opera Lohengrin in Moscow. He said “I saw all my colours in spirit, before my eyes. Wild, almost crazy lines were sketched in front of me.” In 1911, after studying and settling in Germany, he was similarly moved by a Schoenberg concert of 3 Klavierstücke Op. 11 and finished painting Impression III (Konzert) two days later.

Impression III (Konzert) – Kandinsky

When studying the music of known synesthetic composers, it’s important we bear in mind what the composers were experiencing when writing it as it adds another dimension to the music and can change the overall interpretation. It also offers a fascinating link between music and art, adding increased complexity to the process of musical composition.

Twitter: @Music_WHS

http://whs-blogs.co.uk/teaching/steam/