In this week’s WimLearn Morven Ross and Callista McLaughlin explore how passion can build intellectual resilience at A Level.

We are two Early Career Teachers from very different fields – Design and Technology and Classics. However, in our conversations during our time at Wimbledon High School, we have constantly noticed similarities between our approaches to teaching, and the approaches of our students. Perhaps it is because we both teach subjects that are non-compulsory from the Middle School, and almost always sought for their intrinsic value, with our students’ desire to study them stemming from a particular interest and passion, or niche skillset. Given the same sort of motivation is what has led us to teaching, we seek to magnify that motivation in our students, by creating conducive conditions to instil the intellectual resilience prized in A Level students.

Breadth to match depth

In our A Level teaching, we have noticed that the courses in both Product Design, and Latin or Greek, focus on understanding a particular topic or text in depth, compared to the, albeit more cursory, breadth which characterises many GCSE courses. To build intellectual resilience though, students need to indulge their curiosity and open themselves up to further aspects of the subject at hand, weaving a safety blanket of breadth to match that depth. Furthermore, due to the intrinsically specialist nature of our subjects, our aim is not solely to get pupils through their A Levels, but to create Classicists and Product Designers.

While the A Level Latin candidates this year would only be tested on 124 of the 9883 lines of Virgil’s Aeneid in Latin, and only the twelfth of the twelve books in English, to inject real meaning and fulfilment into this study, the students are encouraged to read the whole of the Aeneid in English. While this kind of breadth would be of some obvious help to A Level, we have found the magic really starts when the breadth goes further. In Product Design, students are encouraged to go beyond the curriculum. The A Level Microsoft Team is used as a platform for inspiration; we post interesting products and articles as well as links to industry talks and external competitions. These posts create meaningful small talk at the start of subsequent lessons, bridging the gap between the outside world and the A Level in a way that can often be a nice segue into the lesson content. Socratic questioning is seen across departments as a method of building intellectual resilience – it’s interesting to note that the Socratic dialogues written by Plato would often start with this kind of small talk.

We would love to know…

In what ways to do you encourage students to go beyond the curriculum and engage with your subject from a purely curious yet scholarly viewpoint?

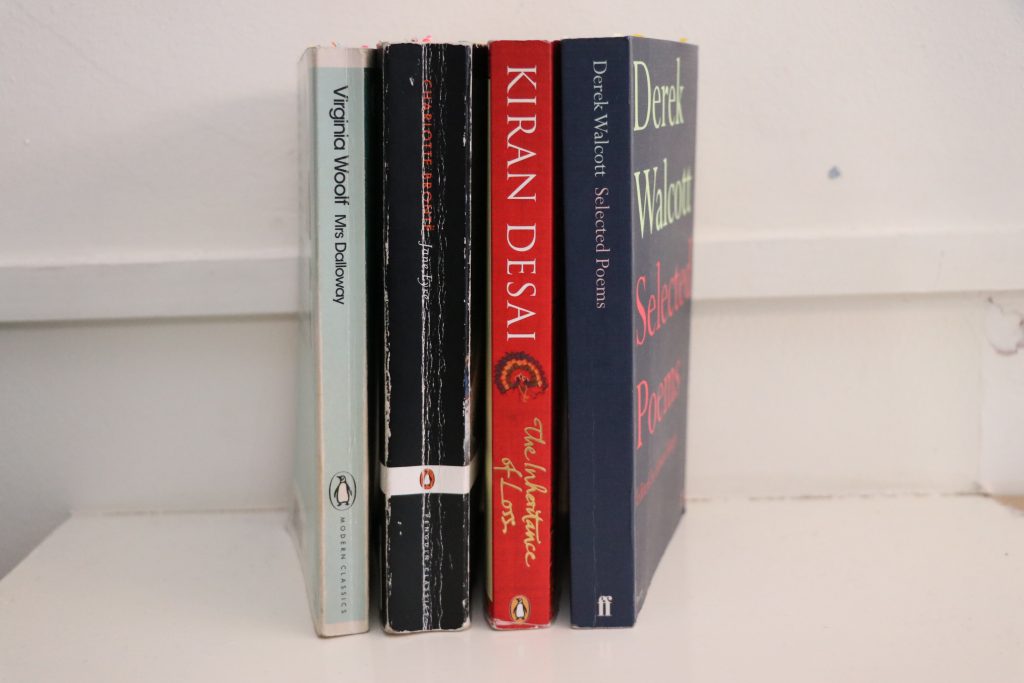

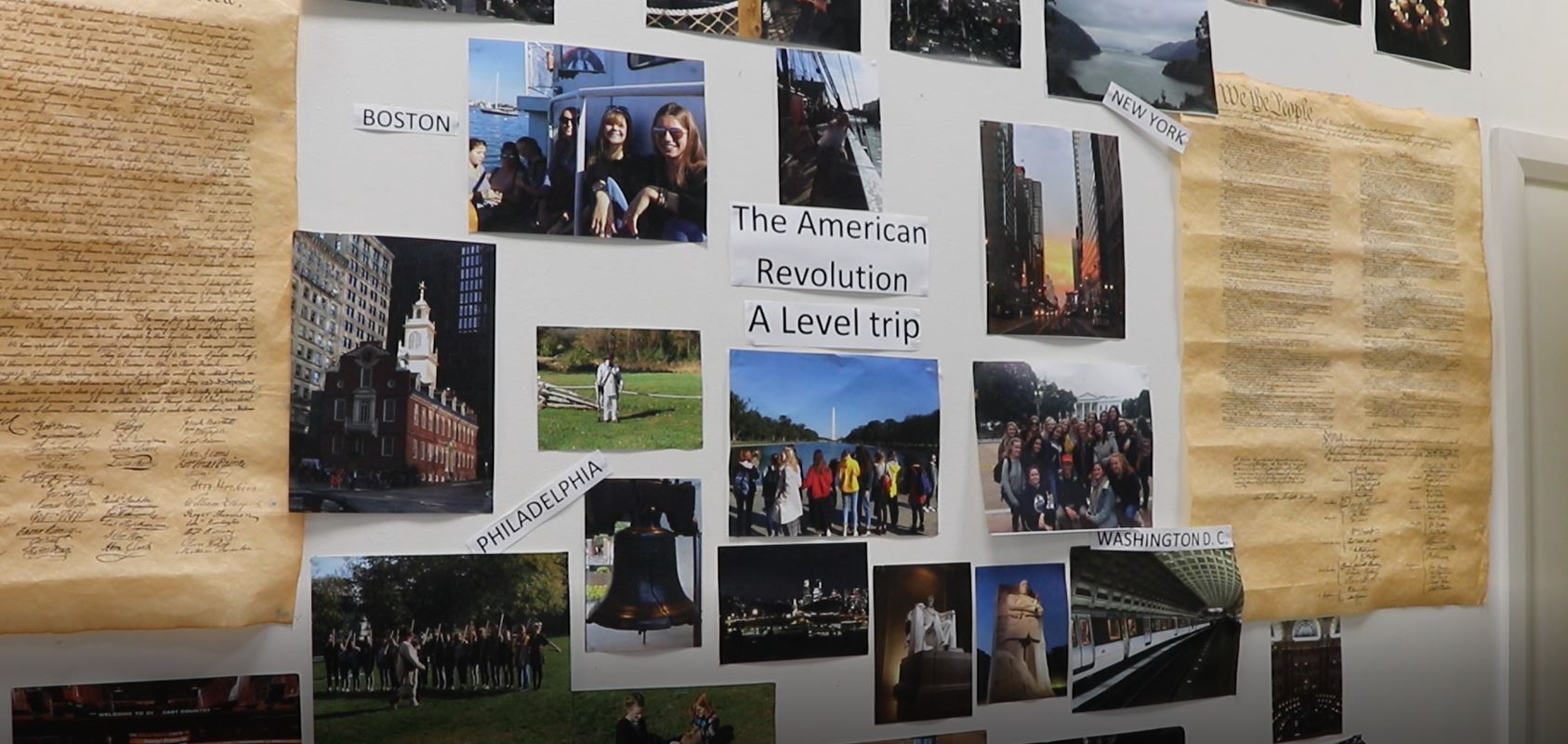

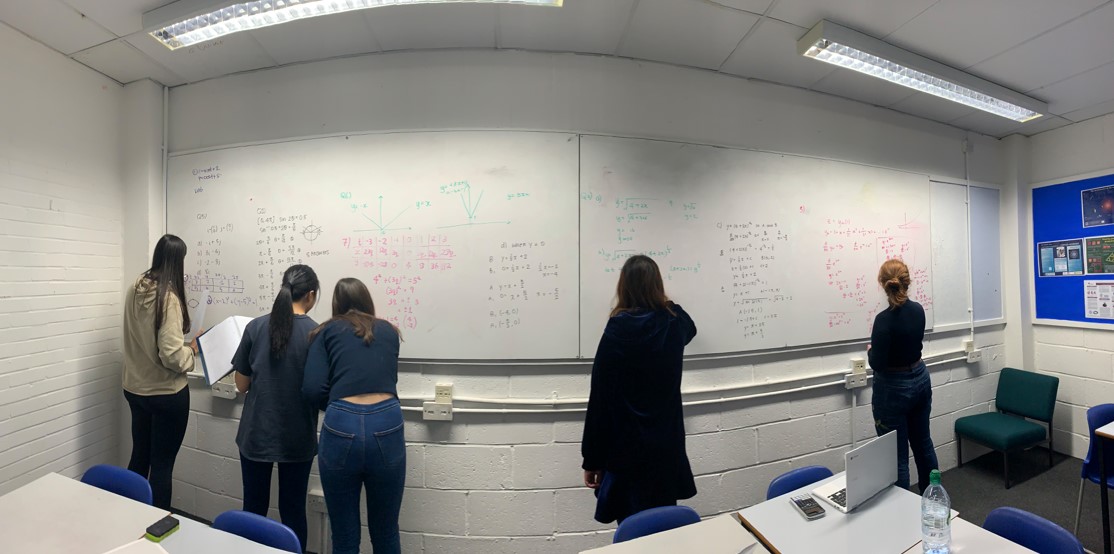

Modelling and nurturing passion

For students looking to continue to study our subjects in the future, the subject must exist for them outside as well as inside the classroom. We as teachers must model this. A Level Product Design students have come to understand that having a design sketchbook is not an over-ambitious and fanciful suggestion of their teachers, but an achievable must-have for a Product Designer. Students highlight how inspiring it is to see their teacher’s current design work in a raw, unfiltered sketchbook as well as hearing about, and seeing, their prior industry experience via their design portfolios. We like to model everyday subject engagement in Classics too: a small book of Sappho, tried and tested by their teacher as hand-bag size, is a proven realistic acquisition for a Classical Civilisation student with a long reading list.

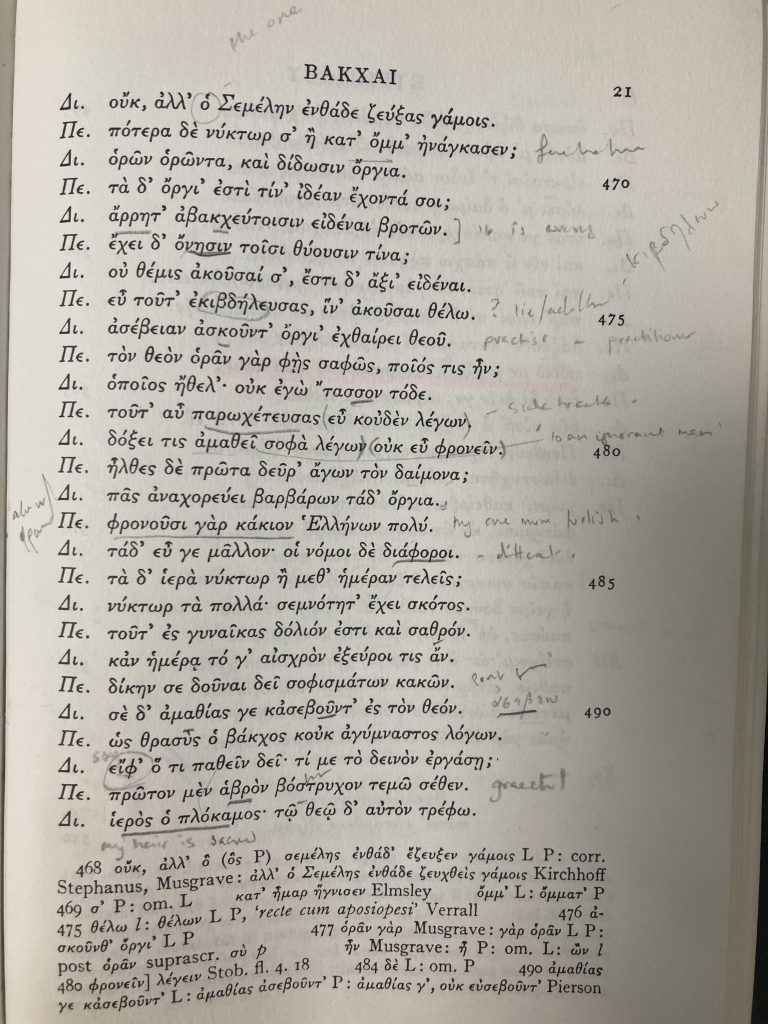

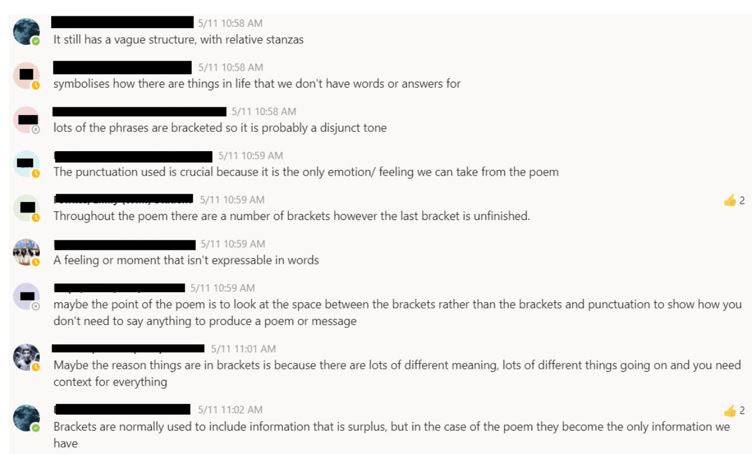

This is not to suggest a binary between the prescriptiveness of the A Level syllabus and the passion that can be nurtured outside of it. We love finding quick hacks to exploit the joy our subjects can offer even in the most pressed moments of the course. In A Level set text teaching, reading the lines of Classical verse as a class in the metre reminds pupils that they are reading beautiful poetry before settling down to find the main verb for translation. In Product Design, the teacher stopping to scribble a rough napkin sketch in the middle of a lesson is not uncommon. After all we never know when inspiration might strike.

We would love to know…

In what ways to do you model an element of your subject to students in order to nurture their passion?

Care through challenge

We have found that when these attitudes are inculcated and this environment is created, intellectual resilience follows. Because young people in particular push harder when it comes to things they really care about. If you’re sketching all the time, you become comfortable with raw, unfiltered work. In A Level Product Design lessons, work is regularly laid on the table for open and honest critique by the class; this builds a culture of trust. True designers know the process is what’s important. Classicists can learn from this too; giving a pupil a deliberately hard Latin unseen and praising their guesses, or critiquing them from a place of mutual understanding, irrespective of their accuracy, can produce the most fascinating linguistic conversations.

As we look ahead to the vast openness of the summer holidays, Product Design are devising a list of intellectual challenges to stretch the pupils. Classics are always elaborating on their reading lists so that the aim of summer reading is not to get ahead for the A Level, but to warmly challenge their students to be Classicists all year round.

A final thought…

How would you answer this question, posed by an A Level Product Design student this week, based on entirely independent and whimsical research. The question happens to be of just as much interest to a student of ancient languages. So, in true STEAM+ fashion, how would you use your language and design skills to signpost radioactive material which will outlive us all, and potentially the human race…?

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200731-how-to-build-a-nuclear-warning-for-10000-years-time