Physics teacher Helen Sinclair investigates the claim that ‘hard maths’ puts off girls from studying Physics, and finds that the truth is much more complex than this, and is not limited to gender. She explains how she makes lessons and clubs inclusive.

In April, the Government’s Social Mobility Advisor, Katherine Birbalsingh, told MPs that girls are less likely to choose Physics A-Level because it contains too much “hard maths”. She added, “Research generally, they say that’s just a natural thing… I mean I don’t know. I can’t say – I mean, I’m not an expert at that sort of thing. That’s what they say.”

This provoked unsurprising outrage from those who have spent their working lives trying to understand and solve this problem. Dame Athene Donald, Professor Emerita of Experimental Physics at the University of Cambridge, summed up some of the key points when she spoke to the same committee a few days later.

“[It] starts really young, the message society gives is that they (Physicists) are white males, and I think there is evidence to show that if you are black or if you are a woman, you don’t see yourself fitting in… The internal messages that girls may believe – if teachers aren’t actively trying to counter that, they may not realise that the girls are being driven by things that aren’t their natural choices.”

Whilst Ms Birbalsingh may have subsequently backtracked somewhat from her comments, the question still lingers – why is there such a gender gap in Physics?

A diversity gap

The problem of diversity in Physics is not new. The percentage of female A-Level Physics students has stubbornly remained around 20% for nearly 30 years. In 2011 the Institute of Physics reported that almost half of all mixed schools had no girls studying Physics A-Level and that girls were almost two and a half times more likely to study Physics if they came from a girls’ school rather than a co-ed school. Five years later, the picture had barely changed. Their detailed research over the last decade shows that the causes extend far beyond the Physics classroom: schools with low numbers of girls in Physics often showed gender imbalances in other subjects too, such as English. Furthermore, their research revealed that it wasn’t simply a problem of gender. All kinds of minorities are less likely to study Physics.

Girls often enter the Physics classroom with a narrower range of early, concrete preparations for Physics compared to boys, stemming from the very different toys and pursuits that they are still often exposed to in their early years. This can make it hard for them to easily identify links between core ideas studied in the classroom and their applications to their lives and career ambitions. Research shows that by exploring these applications within lessons, all students (and particularly girls) are better able to see the relevance of Physics as a subject.

Making Physics teaching more inclusive

Girls are also more likely to see value in subjects that link to social and human concerns. Because Physics tends to simplify situations in order to understand key principles, these links can often be lost, making concepts seem irrelevant to students’ lives. By making a conscious effort to link concepts to real-world problems and societal challenges, we can convey the subject’s importance more effectively to girls. For example, this year we have explored Energy Use and Climate Change with Year 9; the Chernobyl disaster, the USSR and the war in Ukraine with Year 10; and the how seatbelts are designed for men and Tonga’s damaged data cable with Year 11.

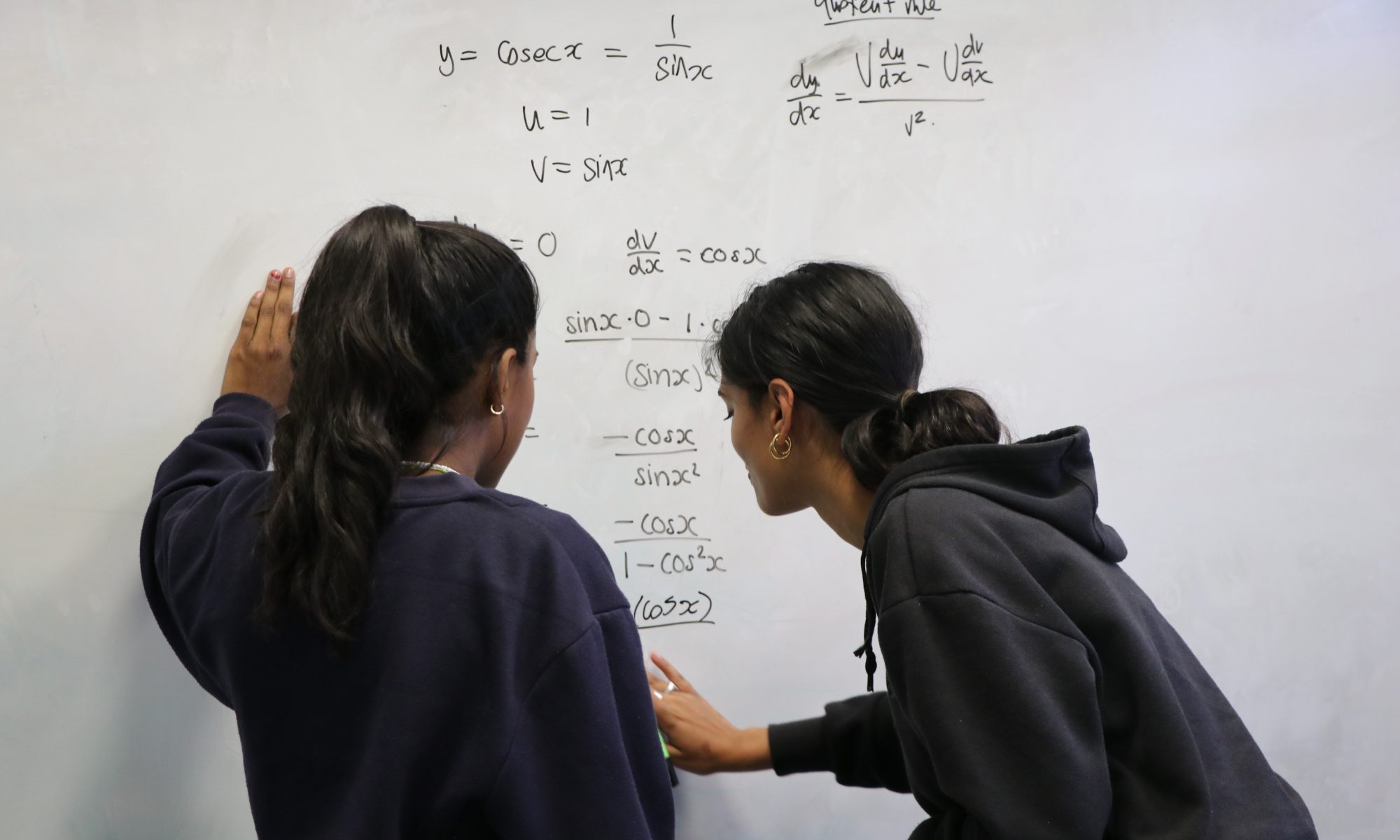

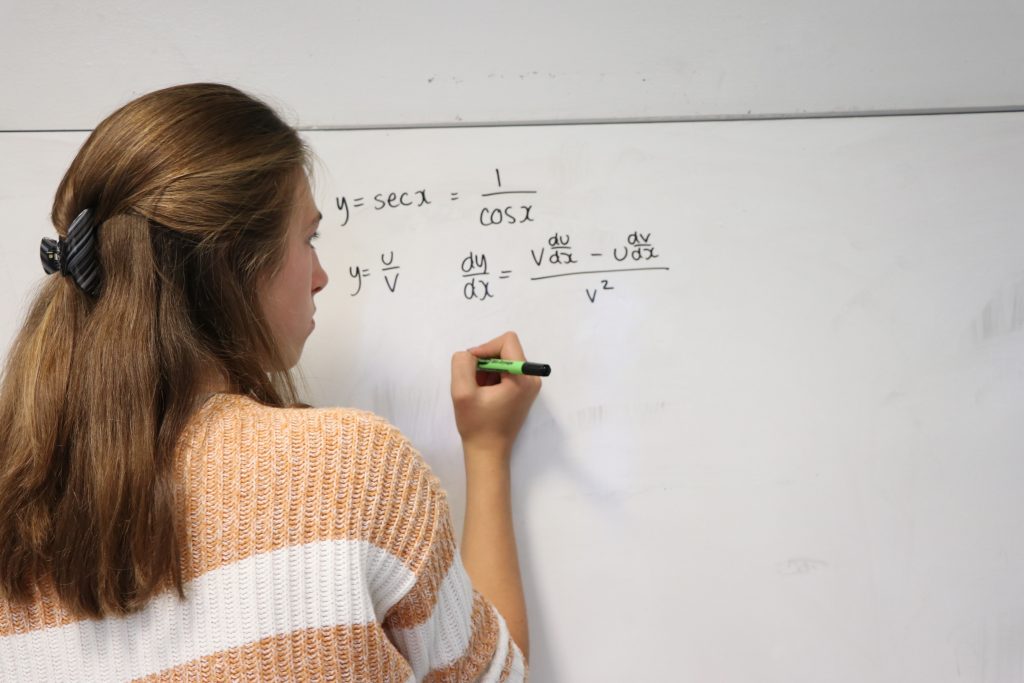

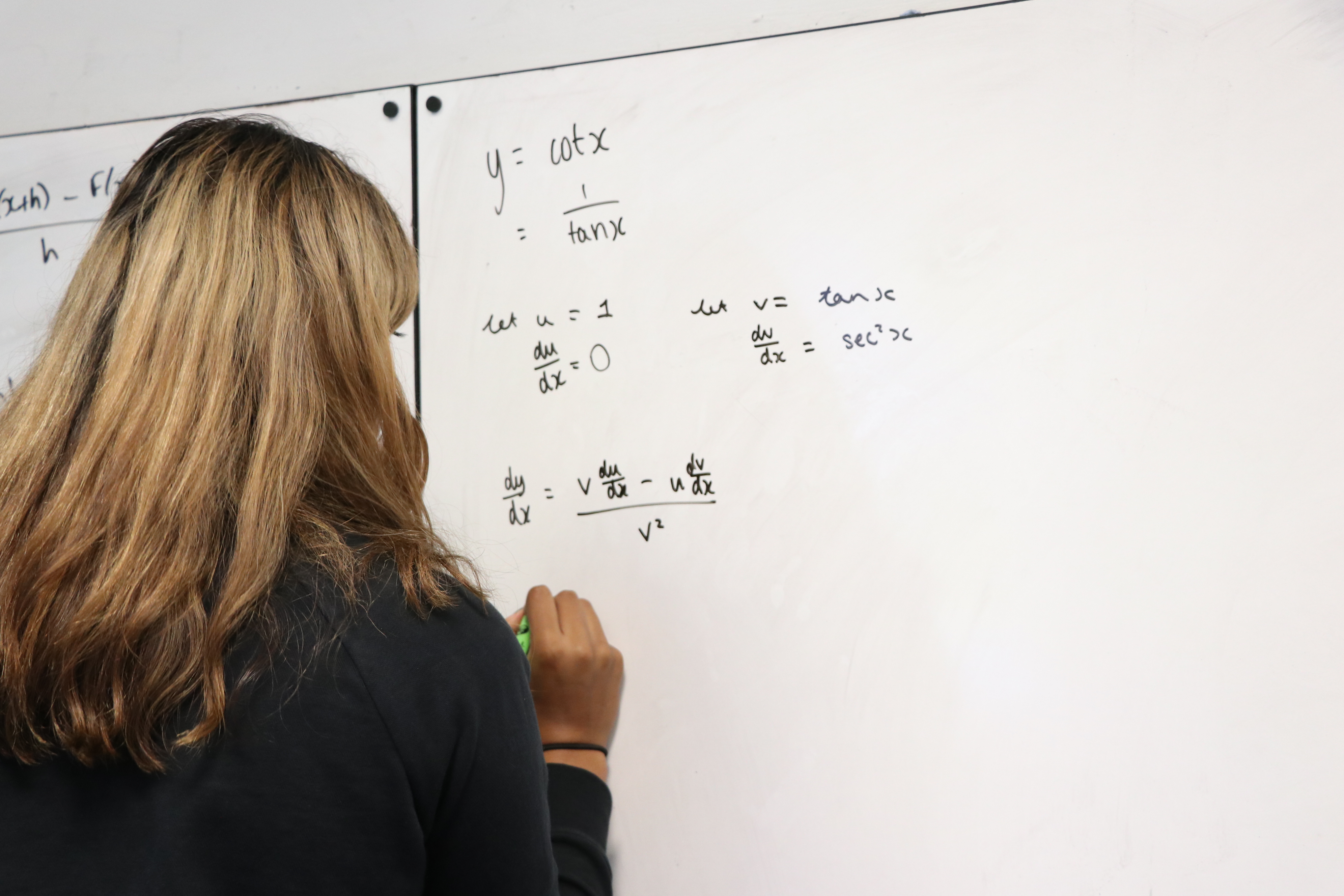

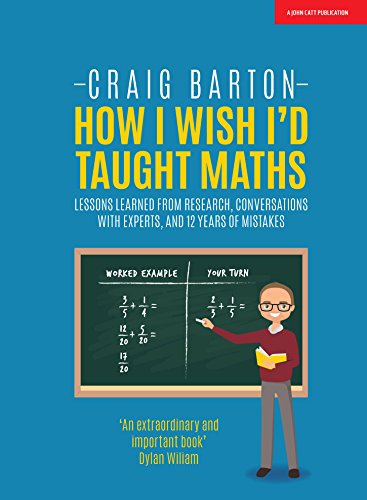

Research has shown that girls’ self-concept is lower than boys. They also are more interested in achieving mastery of a subject. This is particularly noticeable in our students, who often try to judge their success by comparing their achievements with others’, and who can look at anything other than perfection as a failure. This culture of perfection (which extends well beyond the Physics classroom) can make it harder for students initially to engage with more challenging problems. One of the key ways of supporting students through this is to create a more relaxed atmosphere, allowing them to discuss different approaches, and identify and learn from their mistakes. Embedded use of the Isaac Physics website in lessons has proved a powerful tool to help our students feel successful and identify areas for improvement quickly.

Our Physics lunch club was formed in partnership with some Year 10s who wanted to tackle challenging problems. At first it was run in an ordinary classroom, but it soon became clear that in this formal environment, students were on edge. The following week we relocated to the new private dining room on site. Students ate their lunch and chatted at the same time as completing questions. The informal atmosphere encouraged them to discuss problems, rather than try to solve them individually. It was fascinating to see how the setting and approach of the session had such a significant impact on students’ enjoyment and engagement.

Whilst there are many things an individual teacher can do, it is important to remember that the impacts of these interventions are likely to be limited. Above all, the research consistently shows that girls’ views on Physics are shaped by their interactions in wider society and the bias that is still pervasive there. Surely it is our responsibility as educators to openly address this, not just for the benefit of our students, but also for the benefit of our society.

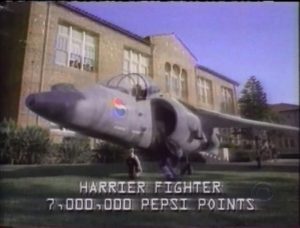

One example of maths going wrong is when in 1995 Pepsi ran an advert where people could collect Pepsi points and trade them in for Pepsi-branded items. Points could be collected through purchasing Pepsi products, or through paying 10 cents per point. For example, a T-shirt was worth a mere 75 points whilst a leather jacket was worth 1,450 points.

One example of maths going wrong is when in 1995 Pepsi ran an advert where people could collect Pepsi points and trade them in for Pepsi-branded items. Points could be collected through purchasing Pepsi products, or through paying 10 cents per point. For example, a T-shirt was worth a mere 75 points whilst a leather jacket was worth 1,450 points.