Mr Bob Haythorne, Director of Academic Administration and Data at WHS, looks at the processes involved to craft a whole school academic timetable.

“I don’t know how you do it!”

“I don’t know why I do it!”

If I had £1 for every time I’ve had that exchange about timetabling over the years, I think I’d have been able to retire a few years ago. If we add the other old chestnuts – “Why don’t you just reuse the same timetable every year?” and “Can’t you just get a computer to do it all?”– I think I’d have been able to retire before I’d even started! I’ve been asked to write this WimTeach blog about timetabling, but I’m not sure I can do it justice within the allowed wordage: there are textbooks on it and the standard training course is three days long, so this is just a potted summary of the process.

It actually starts a long time before September; in fact, we need to have a pretty good idea of what we’re offering to Year 12 over fifteen months earlier, when we hold our ‘Into the Sixth’ events. This can be affected by the addition of new subjects, the removal of others and changes to the whole structure brought about by new government policies. Straightaway, we can start to see why it’s not possible to copy the timetable over from one year to the next. Add in staff moves, random variations in popularity of different optional subjects at GCSE and A-Level, and increases in the size of year groups and it soon becomes obvious why everyone retracts that question after a moment’s thought. A senior school timetable is critically dependent on the GCSE and A-Level options, so a great deal of time is spent with individual girls in Years 9 and 11, mainly in the Autumn and early Spring Terms, to help them choose and to get the information from them that we need to make a start.

With options in by February Half Term, the fun begins! The first task is to analyse the numbers to see what the staffing implications are. Will we have enough Mediæval Tapestry teachers? Or can we really justify running Industrial Botany for just one girl? We need to give our part-time teachers a term’s notice of variations in their hours and any recruitment ideally should be sorted before the Easter deadline for giving notice. Whilst the Head and HR team are resolving those issues, we are crunching these options to fit them into option ‘blocks’ – groups of subjects where classes will be taught simultaneously. (The number of option blocks is equal to the number of subjects the girls are allowed to opt for). There is software to help with this, although my experience is that if you ask the program to create a scheme from the raw information, it will give a ridiculous answer, if it can give one at all. (We don’t want all three Mediæval Tapestry groups in one block if there are only two teachers and only one specialist classroom, for instance; really we want them spread across three different blocks). I find that manually allocating about half the groups into blocks based on common sense and experience and letting the software solve the rest works best. It will then allocate girls to groups and you can see whether some groups are too big or too small, and you can experiment with moving them around until you get a solution you like. Whether it will timetable is still another matter!

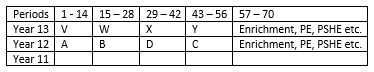

‘Blocking’ is the first stage of actual timetabling and can be a major task in its own right. This is where we take the 70 periods of our timetable and draw up a table of what could be going on at the same time. At this stage, its just 70 periods, labelled 1 to 70 – there is no thought about when each period will happen, except for certain fixed periods, like Y11 – 13 Enrichment, which has to be on Thursday afternoon because of its links with outside agencies. Because Enrichment has so many small groups, it places a strain on staffing, so we have usually scheduled the largest Year group in Years 7 – 10 to have PE at this time.

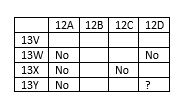

How the Year 12 and Year 13 option blocks mesh together is critical. We draw up a table that might look like this:

(In practice, I would show all the actual subjects in each block – usually between 8 and 12 different groups – so that I can see the clashes.)

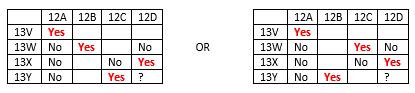

The ‘No’s are because, say, the planned scheme for Year 12 block A contains three subjects where we only have one teacher, or one necessary specialist room, and these three subjects happen to spread across three different Year 13 (i.e. current Year 12) blocks – W, X and Y. Something similar will be the case for 12C and 13X clashing, and for 12D and 13W clashing. In this example, we see that all 12A lessons will have to be timetabled simultaneously with all 13V lessons. The ‘?’ for 12D and 13Y might mean that it probably could work, but ideally we would keep them apart. This means there are really only two solutions:

These will then determine the underlying structure of the entire timetable. Making the decision about which one to go with is nerve-wracking – one might turn out weeks later to have been a poor choice! These go into the Blocking table:

It gets a lot more fragmented after this. Ideally, two Year 11 option blocks (7 periods each) would sit nicely under each Year 12/13 pairing, but it never works out that neatly. For a start, there are only six option blocks, not eight, and Maths and English have more than 7 periods. Again, there are restrictions caused by limited specialist rooms and/or teachers that determine which Year 11 blocks can and cannot go under which Year 12/13 pairings. And after playing with this for a week or two, it’s time to insert Year 10, with the same issues, but with complications like Enrichment and PSHE being at the same time for Years 11 – 13, but there’s no Enrichment in Year 10 etc. Bear in mind that the table above just shows one column for periods 1 to 14: the reality is one column for each period …and a very wide table! By the way, it’s probably around Easter by now.

Some timetablers would do all their blocking (down to Year 7) before attempting to schedule the lessons into actual periods on actual days, but either because I’m impatient or because we have so many restrictions on what can happen when, I tend to start scheduling now. (E.g. we have a large proportion of part-time staff, who – funnily enough – don’t think it’s really part-time, if you have to be available for all 70 periods, with a small number of lessons randomly scattered around!) Now, at last, we turn to the timetabling software. Again, you could try inputting all the information and hitting the ‘Autoschedule’ button, but when it’s finished trying (a few days later), it will either have produced garbage or – more likely – failed. The problem is that there are too many arbitrary decisions that you would have to make when inputting all that information, so it’s better to build things up steadily, seeing what’s working and trying to keep as much flexibility as possible for later stages. An example of an arbitrary decision would be to allocate all the teachers to the incoming Year 7 groups: there is no point being specific about exactly who is going to teach English to which class, because any of the four Year 7 English teachers could take any group, without needing to worry about continuity from Year 6. Doing so means creating an unnecessary restriction; doing so across all subjects is just mad!

It starts with the fixed items: Enrichment, Year 12/13 PE, PSHE, HoYs meeting, SMT meeting and lock these in place. Then the Year 12/13 pairings, bearing in mind we want double periods etc.. Then Year 11. Then realise this isn’t going to work, because of some staffing issue. Rip out Years 11 – 13 and start again. Repeat as necessary until there’s a satisfactory solution. Add in Year 10. Take out Year 10 and adjust the option scheme. Retry Year 10….

This constant back and forth continues for a few weeks. We now have some limited options in Year 9, so it’s a similar story and that takes about a week to sort out. Finally, Years 8 and then 7, where there is much more flexibility, as one class can have Geography whilst another is studying English and another Art etc.. Even so, that’s another week and it’s May Half Term already – or later!

So, why do I do this? Because it’s a huge puzzle, but it’s a puzzle where the answer isn’t in the back of the book or in tomorrow’s edition; it’s a puzzle where you have to keep changing the problem when it can’t be solved to one you think you might be able to solve… or might not, so you try turning it into yet another problem.

But when that final piece of the jigsaw slots into place, that multi-way swap that you think will do the trick does do the trick, that opportunity to move something that you thought you remembered turns out to be right, then I know why I do this!

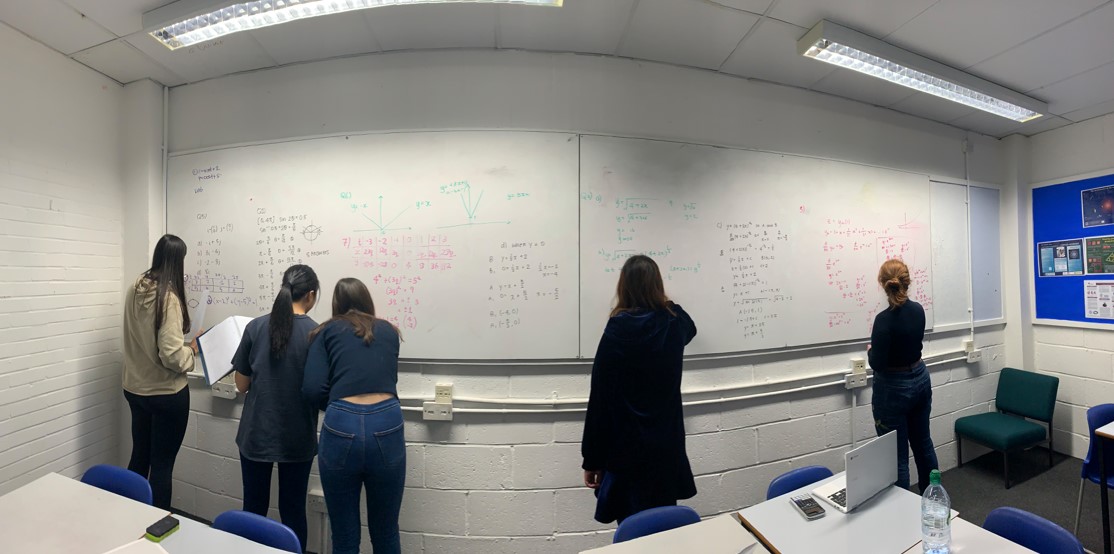

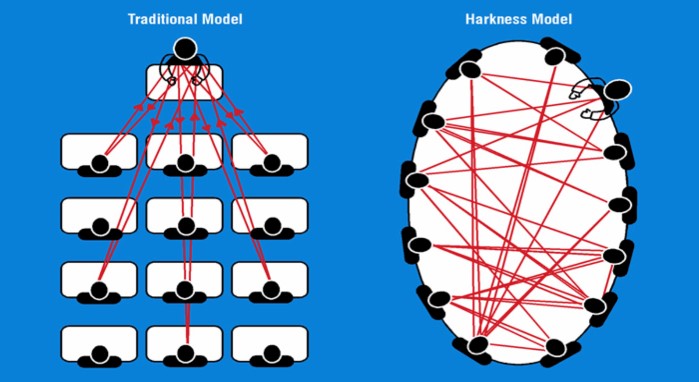

As the lessons progressed, I started enjoying this method of teaching as it allowed me to understand not only how each formula and rule had come to be, but also how to derive them and prove them myself – something which I find incredibly satisfying. I also particularly like the fact that a specific problem set will test me on many topics. This means that I am constantly practising every topic and so am less likely to forget it. Also, if I get stuck, I can easily move on to the next question.

As the lessons progressed, I started enjoying this method of teaching as it allowed me to understand not only how each formula and rule had come to be, but also how to derive them and prove them myself – something which I find incredibly satisfying. I also particularly like the fact that a specific problem set will test me on many topics. This means that I am constantly practising every topic and so am less likely to forget it. Also, if I get stuck, I can easily move on to the next question. Moreover, I very much enjoyed seeing how other people completed the questions as they would often have other methods, which I found far easier than the way I had used. The other benefit of the lesson being in more like a discussion is that it has often felt like having multiple teachers as my fellow class member have all been able to explain the topics to me. I have found this very useful as I am in a small class of only five however, I certainly think that the method would not work as well in larger classes.

Moreover, I very much enjoyed seeing how other people completed the questions as they would often have other methods, which I found far easier than the way I had used. The other benefit of the lesson being in more like a discussion is that it has often felt like having multiple teachers as my fellow class member have all been able to explain the topics to me. I have found this very useful as I am in a small class of only five however, I certainly think that the method would not work as well in larger classes.

Distributed systems such as Bitcoin’s involve a negative externality that causes over investment in computer hardware as the expected marginal revenue from the individual miners is increasing with the amount of computing power that they individually have. Not only does this increase their own marginal cost but it increases the competition within the system and thus the cost is also increasing across the entire network. “Cetirus paribus” economic theory would suggest that in equilibrium all miners are inefficiently investing in hardware while receiving the same revenue that they would have had they not invested in the extra computing power. This behaviour is irrational as it is increasing the computing power across the entire network making it harder for them to succeed individually.

Distributed systems such as Bitcoin’s involve a negative externality that causes over investment in computer hardware as the expected marginal revenue from the individual miners is increasing with the amount of computing power that they individually have. Not only does this increase their own marginal cost but it increases the competition within the system and thus the cost is also increasing across the entire network. “Cetirus paribus” economic theory would suggest that in equilibrium all miners are inefficiently investing in hardware while receiving the same revenue that they would have had they not invested in the extra computing power. This behaviour is irrational as it is increasing the computing power across the entire network making it harder for them to succeed individually.