Pheoebe C in Year 12 explores the evolution of the kirtle, from its origins to its more modern form, the dress.

A kirtle is a one-piece garment that was popular in Western Europe from the early Middle Ages up into the 17th century. Mentions of the kirtle date back to as early as the 10th century[1], and painted depictions survive from throughout the 17th century[2]. Initially worn by both men and women (although men’s kirtles are often referred to as ‘cotehardies’ in modern scholarship, they are fundamentally the same[3]), men’s fashion gradually shifted away, towards the shirts and trousers we see in menswear today. However, the basic concept of the kirtle still survives in modern-day dresses, making it perhaps the most influential garment in the entire history of Western fashion.

The kirtle was the first western ‘dress’, so to speak. Although clothing had also previously consisted of one long garment draped over the whole body, the kirtle was made to fit around the human body, rather than be wrapped and manipulated with folds and belts until it fit. Additionally, it needed no extra closures such as pins or brooches, as previous garments had done. Examples of the kirtle’s predecessor include Roman togas (and other robes), as well the Anglo-Saxon peplos[4]. These garments were loose-fitting and tended to be made of just a large rectangle (or two) of fabric, pinned or tied around the body, and often sleeveless. The kirtle was also one of the first Western garments which required no extra undergarments (although they were often worn in combination with other garments for warmth or practicality anyway). They had sleeves and were long enough to also cover the legs, circumventing the need for several additional items of clothing, and instead combining them all into one.

Kirtles started off as both under and outerwear, and it wasn’t uncommon to wear both an under-kirtle and an over-kirtle. The under-kirtle would have been made from a cheaper fabric that could survive frequent washing, whereas the outer-kirtle would be finer or decorated in some way. Kirtles were usually woollen, however, linen was sometimes used depending on environment and availability[5]. As time went on, the upper classes progressed to only wearing kirtles as undergarments, whereas the lower classes used them as main outer-garments for much longer[6].

Of course, since the popularity of the kirtle lasted over half a millennium, some evolution and change in style was inevitable. Early kirtles were loose-fitting and didn’t have waist-seams. However, by the 15th century they were skin-tight and then evolved to consist of separate skirts that were pleated or gathered before being attached to the bodice[7]. Kirtles were closed using lacing along the front, sides or back of the garment, although earlier examples of kirtles have no lacing at all. Since early kirtles were loose-fitting and had relatively wide necklines, lacing was unnecessary as they could just be put on over the head. Later, tighter kirtles also acted as a kind of prototype for the corset; they provided the kind of support we now receive from a modern bra.

For example, here is a reconstruction of a 14th-century kirtle that I made a few years ago, versus the 17th-century one I made this summer.

Notice the stark difference in styles. Although, visually, they appear more different than similar, the fundamental and defining feature of the kirtle remains: a one-piece skirted garment.

Eventually, the kirtle fell out of fashion in favour of separate skirts and bodices among all classes. By the 18th century, there are barely any depictions of kirtles in art, even among lower-class and rural communities. While this development was inevitable since aristocratic fashion had long abandoned the kirtle in favour separate skirts, and working-class fashion has always followed upper class fashion- just at a delay of several decades- practicality was likely a major factor in this evolution. Combining a skirt with a separate jacket or bodice (still over the top of a shift) allowed the wearer to have more freedom in what they wore and saved unnecessary washing. It reduced the total number of garments someone needed to have a varied and adaptable wardrobe. It was also cheaper and quicker to make smaller individual pieces as required, rather than entire dresses. Additionally, as structural undergarments became more commonplace (providing bra-like support and shaping the torso, either in the form of early stays, as a pair of jumps, or as boning sewn directly into the bodice), the need for tight-fitting kirtles as supportive garments declined.

The dress did come back into mainstream fashion eventually (after over a century- and even later in upper-class fashion). Although it looks unrecognisable from its medieval ancestor, the concept of the dress as a one-piece flowing garment originated with the kirtle in European fashion. Modern dresses also share this heritage, although construction techniques and style conventions have progressed significantly. In fact, the closest modern-day equivalents to the kirtle are various forms of European folk dress. The legacy of the kirtle lives on through garments such as the German Dirndl, a type of folk dress based off rural Alpine clothing in the 16th-18th centuries[8]. The modern Dirndl bares striking resemblance to the 17th century kirtle, and it is fair to presume that this is because one was based off the other, seeing as the kirtle was a very common working-class garment throughout Western Europe (including the Alpine region) at the time. Although it seems modern society has largely forgotten about the kirtle, its lasting impact is undeniably still evident in fashion today.

[1] Anglo-Saxon Female Clothing: Old English Cyrtel and Tunece, Donata Bulotta (https://www.jstor.org/stable/23966300#metadata_info_tab_contents )

[2] ’A Peasant Family at Meal-time’, c1665, Jan Steen

[3] https://rosaliegilbert.com/kirtles.html

[4] Dress In Anglo-Saxon England, Gale R. Owen-Crocker (https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=45RJYhTGZiUC&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false )

[5] https://ateliernostalgia.wordpress.com/2017/03/24/medieval-kirtle/

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kirtle

[7] https://medievalbritain.com/type/medieval-life/clothing/medieval-dress/

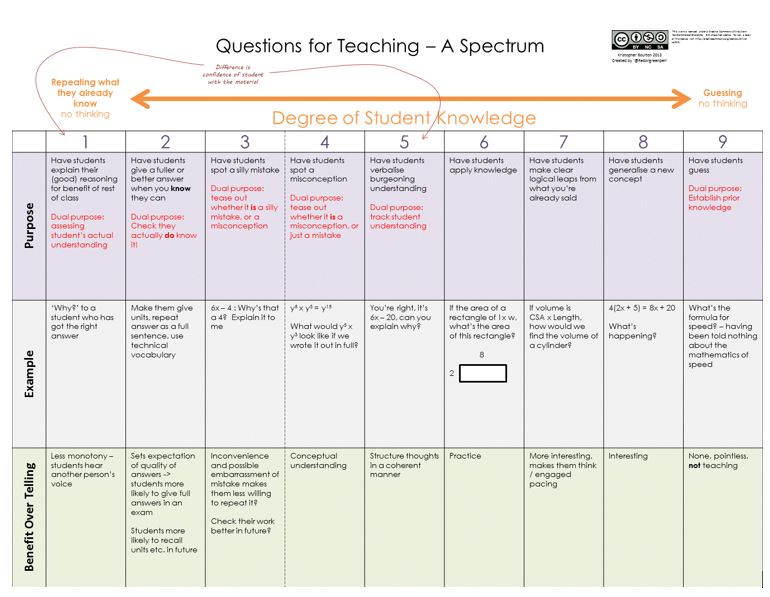

addresses that the question is not why questions are better, it is when. He concluded that: ‘questions can be very effective tools of teaching, but they must be used with incredible care.’ A very structured grid of various question types concluded by him and another blogger can be found here:

addresses that the question is not why questions are better, it is when. He concluded that: ‘questions can be very effective tools of teaching, but they must be used with incredible care.’ A very structured grid of various question types concluded by him and another blogger can be found here: