How can we encourage collaborative learning? Alex Farrer, STEAM Co-ordinator at Wimbledon High, looks at strategies to encourage creative collaboration in the classroom.

Pupils’ ability to work collaboratively in the classroom cannot just be assumed. Pupils develop high levels of teamwork skills in many areas of school life such as being part of a rowing squad or playing in an ensemble. These strengths are also being harnessed in a variety of subject areas but need to be taught and developed within a coherent framework. Last week we were very pleased to learn that Wimbledon High was shortlisted for the TES Independent Schools Creativity Award 2019. This recognises the development of STEAM skills such as teamwork, problem solving, creativity and curiosity across the curriculum. Wimbledon High pupils are enjoying tackling intriguing STEAM activities in a variety of subject areas. One important question to ask is what sort of progression should we expect as pupils develop these skills?

The Science National Curriculum for England (D of E gov.uk 2015) outlines the “working scientifically” skills expected of pupils from year 1 upwards. Pupils are expected to answer scientific questions in a range of different ways such as in an investigation where variables can be identified and controlled and a fair test type of enquiry is possible.

However, this is not the only way of “working scientifically”. Pupils also need to use different approaches such as identifying and classifying, pattern seeking, researching and observing over time to answer scientific questions. In the excellent resource “It’s not Fair -or is it?” (Turner, Keogh, Naylor and Lawrence) useful progression grids are provided to help teachers identify the progression that might be expected as pupils develop these skills. For example, when using research skills younger pupils use books and electronic media to find things out and talk about whether an information source is useful. Older pupils can use relevant information from a range of secondary sources and evaluate how well their research has answered their questions.

The skills that are used in our STEAM lessons at Wimbledon High in both the Senior and Junior Schools utilise many of these “working scientifically” skills and skill progression grids can be very useful when planning and pitching lessons. However, our STEAM lessons happen in all subject areas and develop a range of other skills including:

- problem solving

- teamwork

- creativity

- curiosity

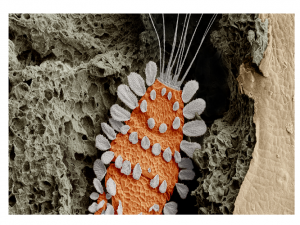

Carefully planned cross-curricular links allow subjects that might at first glance be considered to be very different from each other to complement each other. An example of this is a recent year 10 art lesson where STEAM was injected into the lesson in the form of chemistry knowledge and skills. Pupils greatly benefited from the opportunity to put some chemistry into art and some art into chemistry as they studied the colour blue. Curiosity was piqued and many links were made. Many questions were asked and answered as pupils worked together to learn about Egyptian Blue through the ages and recent developments in the use of the pigment for biomedical imaging.

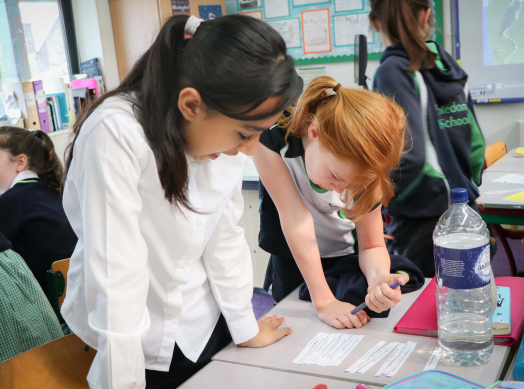

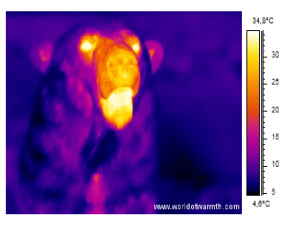

There are many other examples of how subjects are being combined to enhance both. The physiological responses to listening to different types of music made for an interesting investigation with groups of year 7. In this STEAM Music lesson pupils with emerging teamwork skills simply shared tasks between members of the group. Pupils with more developed teamwork skills organised and negotiated different roles in the group depending on identified skills. They also checked progress and adjusted how the group was working in a supportive manner. A skill that often takes considerable practise for many of us!

Professor Roger Kneebone from Imperial College promotes the benefits of collaborating outside of your own discipline. He recently made the headlines when he discussed the dexterity skills of medical students. He talks about the ways students taking part in an artistic pursuit, playing a musical instrument or a sport develop these skills. He believes that surgeons are better at their job if they have learned those skills that being in an orchestra or a team demand. High levels of teamwork and communication are essential to success in all of those fields, including surgery!

Ensuring that we give pupils many opportunities to develop these collaborative skills both inside and outside of lessons is key. We must have high expectations of progression in the way that pupils are developing these skills. Regular opportunities to extend and consolidate these important skills is also important. It is essential to make it clear to pupils at the start of the activity what the skill objective is and what the skill success criteria is. It is hard to develop a skill if it is not taught explicitly, so modelling key steps is helpful as is highlighting the following to pupils:

- Why are we doing this activity?

- Why is it important?

- How does it link to the subject area?

- How does it link to the real life applications?

- What skills are we building?

- Why are these skills important?

- What sort of problems might be encountered?

- How might we deal with these problems?

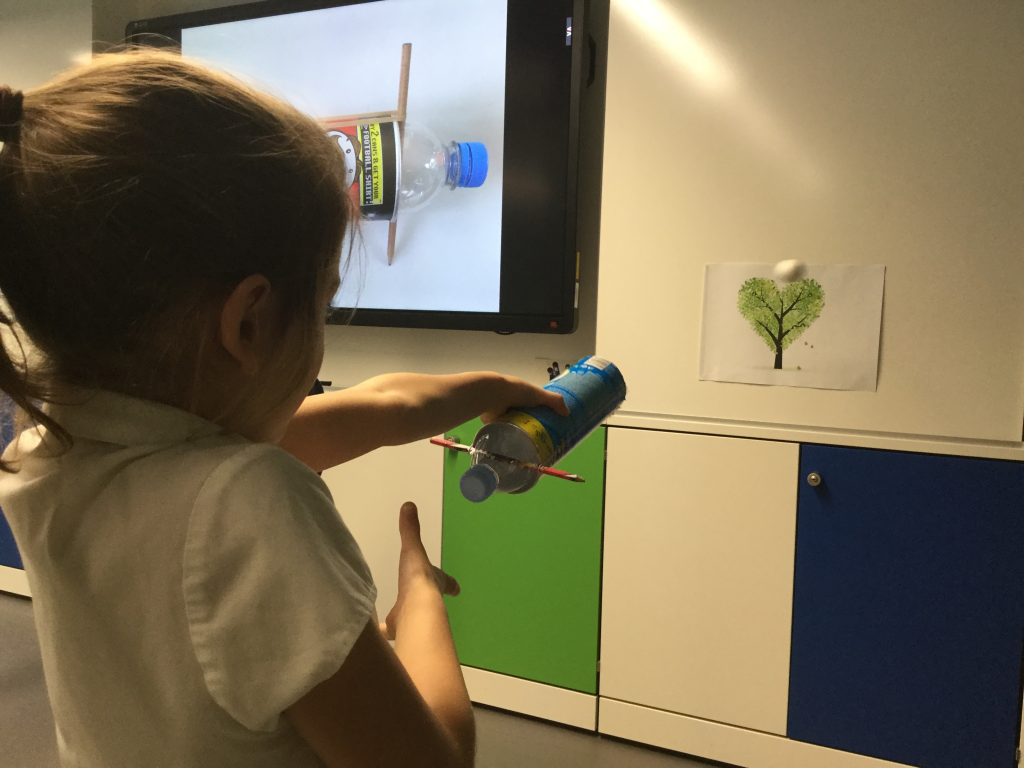

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.

STEAM lessons at Wimbledon High are providing extra opportunities for pupils to build their confidence, and to be flexible, creative and collaborative when faced with novel contexts. These skills need to be modelled and developed and progression needs to be planned carefully. STEAM is great fun, but serious fun, as the concentration seen on faces in the STEAM space show!

Twitter: @STEAM_WHS

Blog: http://www.whs-blogs.co.uk/steam-blog/

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

At school, I lead the annual trip for students in Year 10 – Year 13 to Poland, where we visit Auschwitz concentration camp and Oskar Schindler’s factory. When he died, Oskar Schindler asked to be buried in Jerusalem, facing the Mount of Olives and his grave is visited by millions each year. On my second day, I searched for his grave. In a way, it was closing a circle. I had visited his factory in Poland, listened to many Schindler survivor testimonies and, of course, watched the film. Here was my opportunity to pay tribute to that awe-inspiring man, who saved so many. His grave had stones placed on top of it, a Jewish tradition to honour the dead. Later in the week, I visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to the Shoah (Holocaust) and saw his tree planted in the ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ – a row of trees placed in memory of all the non–Jews who helped save the lives of Jewish people during the Shoah.

At school, I lead the annual trip for students in Year 10 – Year 13 to Poland, where we visit Auschwitz concentration camp and Oskar Schindler’s factory. When he died, Oskar Schindler asked to be buried in Jerusalem, facing the Mount of Olives and his grave is visited by millions each year. On my second day, I searched for his grave. In a way, it was closing a circle. I had visited his factory in Poland, listened to many Schindler survivor testimonies and, of course, watched the film. Here was my opportunity to pay tribute to that awe-inspiring man, who saved so many. His grave had stones placed on top of it, a Jewish tradition to honour the dead. Later in the week, I visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to the Shoah (Holocaust) and saw his tree planted in the ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ – a row of trees placed in memory of all the non–Jews who helped save the lives of Jewish people during the Shoah.