Following the introduction of a postcolonial literature unit in English Literature this year at A Level, Sarah Lindon writes up reflections from a discussion she had with fellow English teacher James Courtenay Clack and students in Year 13, to reflect on what has been valuable about it and what needs further thought

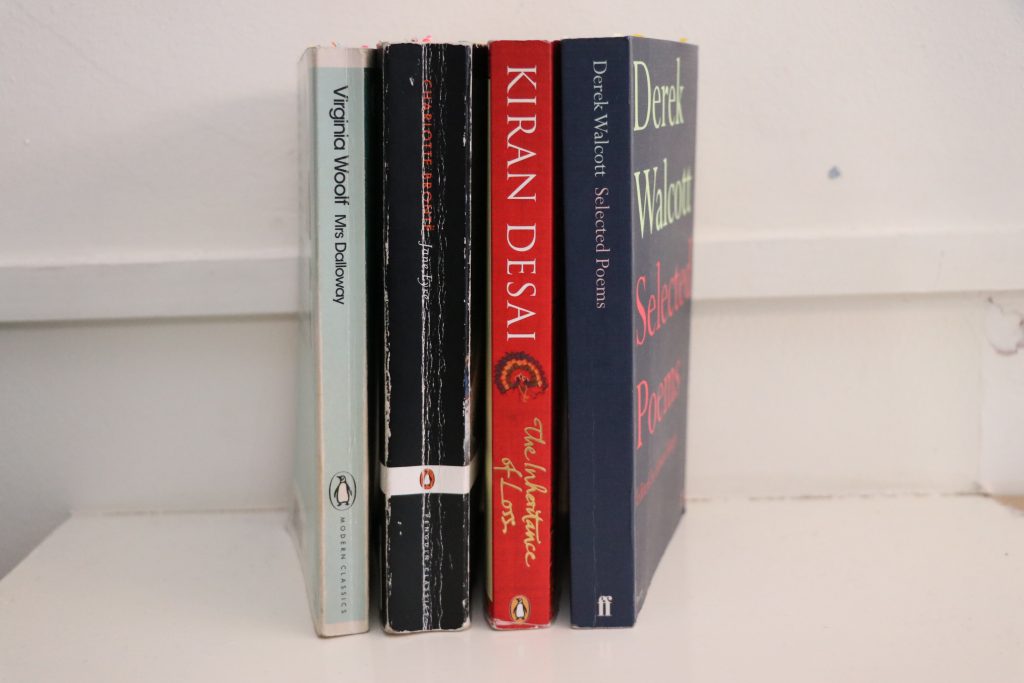

As part of an informal review of the English Department’s work so far on decolonising the curriculum at A Level, we met with Year 13 English Literature students to ask for their feedback before they went on study leave. Those who took part were from the first cohort to undertake the unit on postcolonial texts and theories, which culminated in a coursework task comparing Kiran Desai’s ‘An Inheritance of Loss’ and the poetry of Derek Walcott. We were keen to hear what they thought was of value academically and on a wider human level, and what some of the problems were.

Exploring human experiences

Students told us that while historical accounts gave them factual understanding of aspects of empire, what they valued about looking at Literature was gaining a sense of the plurality of human experiences under colonisation, and appreciating the imaginative depth involved in exploring individual lives through narrative and metaphor. When studying historical facts and following debates in the media, they felt it was easy to become distanced from the subject matter, particularly for those without their own experiences that might resonate with those of oppressed people.

Though they felt in some respects more ‘in touch’ with experiences of colonisation as represented in literature, through having them presented on a ‘narrative plane’, they were nonetheless alert to the danger of becoming ‘narrative tourists’. With Walcott’s poetry especially, metaphor was pinpointed as a powerful vehicle for conveying experiences and ideas. Desai’s use of narrative flashbacks as a tool for interrogating colonialism was highly effective in allowing exploration of the fracturing and evolution of identity. These were methods that they felt gave them deeper insight into the perspectives, thoughts and feelings relating to experiences of imperial domination.

These observations connect with debates about the role literature can play in developing empathy and altruism in readers. Ann Jurecic has suggested that while reading literature does not automatically produce empathy, ‘educators can encourage readers to take advantage of the invitation to dwell in uncertainty and to explore the difficulties of knowing, acknowledging, and responding to others’[i]. Building on this, Omri Cohen suggests the importance of exploring ‘the ways in which reading literature may curb or defeat empathic motivations’[ii]. Both writers engage with Raymond Williams’ view that ‘sympathy experienced [while] reading about…suffering…privatises a social emotion, counteracting the motivation for public action’, and the observations of Lauren Berlant that empathy can be a ‘civic-minded but passive ideal’ and a form of ‘false knowledge’ (cited in Jurecic), and that reading can even provide a ‘false transcendence’ through ‘passive empathy’ (cited in Cohen). Students didn’t seem to have reached a firm standpoint in this regard, but were indeed dwelling in uncertainty.

The importance of listening

Our Year 13s had learnt that the legacy of empire is very much present in the world around them now, which was new to them. All of them had reflected more deeply on their own identities. For those with mixed heritage, this brought increased interest in both areas of privilege and areas of difficulty that their identities entail for them, when considered through exploring figures in the poetry and the novel.

And yet, when the group reflected on whether they now felt more equipped to engage in discussions of empire and its ramifications, they were cautious. While they might have gained a stronger sense of its importance and meanings as a topic, they also felt that such discussions had become harder for them in some ways.

Rather than feeling more inclined to contribute to discussions on topics around empire, racial politics, social justice and inclusion, some students felt they would now have a strong preference for contributing less and listening more, to learn from others. They were aware of how they, like any other group, bring a very specific perspective to these conversations, as members of the majority culture. They had a new appreciation for the strong value of words and their unintended meanings. And they valued what they characterised as a new atmosphere in lessons, where they took more time to listen and connect, saying it wasn’t enough just to bring bubbly energy. They knew that they didn’t always have the answers, and that collaboration and taking in others’ views was essential.

They contrasted this with a kind of complacency they feel susceptible to in relation to the ‘Women in Literature’ component of the course, where their identification with female characters potentially blunts their critical attention and alertness to differences across texts, oeuvres, time periods and cultures. With new awareness of different kinds of oppression, they could now make connections and distinctions in relation to reading for ‘Women in Literature’. They were very engaged by finding new perspectives on more traditionally canonical texts such as Jane Eyre too. Overall, they felt a key legacy of this unit for them as readers was that they would be more aware of the benefits of reconsidering their first reading of a text and exploring other viewpoints.

Reading in the round

One of the most important areas for us to think about as teachers now is how the comparison aspect of the task often led students to read the poetry through their interpretations of Desai’s novel, which meant that the full richness of Walcott’s work and ideas was not brought out as much as we hoped. For practical reasons, students read the novel before turning to the poetry, and we would like to reconsider this for next year, especially since Desai arguably emphasises the traumatic aspect of postcolonial experience above all, while Walcott’s vision acknowledges this but also allows for a generative, creative, plural response to it, and looks to forms of identity that are not just constricted, defined or distorted by colonial legacies

In this vein, we are keen to think further about the dangers of looking at identity in reductive ways. Literature is by its nature multivocal, dialogic, intertextual and complex. The risk of ‘flattening’ texts with one-dimensional readings is one that we need to push against continually, and we will be thinking afresh about this after seeing how that tendency worked out sometimes in this unit to reduce Caribbean literature only to its representation of oppression and suffering , as it sometime does with ‘Women in Literature’ as well. This is diminishing of authors and texts, of what literary craft is about, and of our understanding of human diversity, creativity and identity. We will work further on bringing out more powerfully the communicative and recreative powers of literature, which allow it to ‘talk back’ to power, to social and cultural currents, and to difficult histories and experiences.

[i] Jurecic, Ann. “Empathy and the Critic.” College English, vol. 74, no. 1, 2011, pp. 10–27, http://www.jstor.org/stable/23052371. Accessed 12 May 2022.

[ii] Omri Cohen (2021) Teaching self-critical empathy: lessons drawn from The Tortilla Curtain and Half of a Yellow Sun, English in Education, 55:2, 132-148, DOI: 10.1080/04250494.2019.1686953

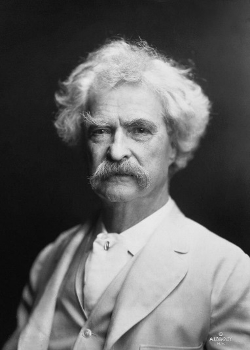

When a playwright is asked ‘what makes me qualified to write this play?’ the immediate assumption can be that our work should be in some ways autobiographical in order to be ‘authentic’ and ‘truthful’. One of the most oft-quoted aphorisms in creative writing is a comment attributed to Mark Twain, “Write what you know.”

When a playwright is asked ‘what makes me qualified to write this play?’ the immediate assumption can be that our work should be in some ways autobiographical in order to be ‘authentic’ and ‘truthful’. One of the most oft-quoted aphorisms in creative writing is a comment attributed to Mark Twain, “Write what you know.”

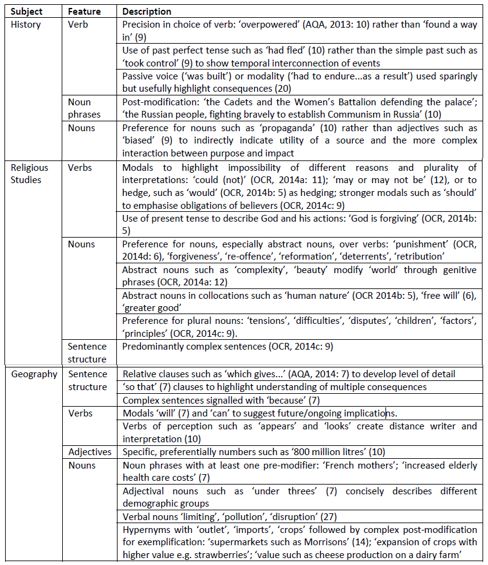

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

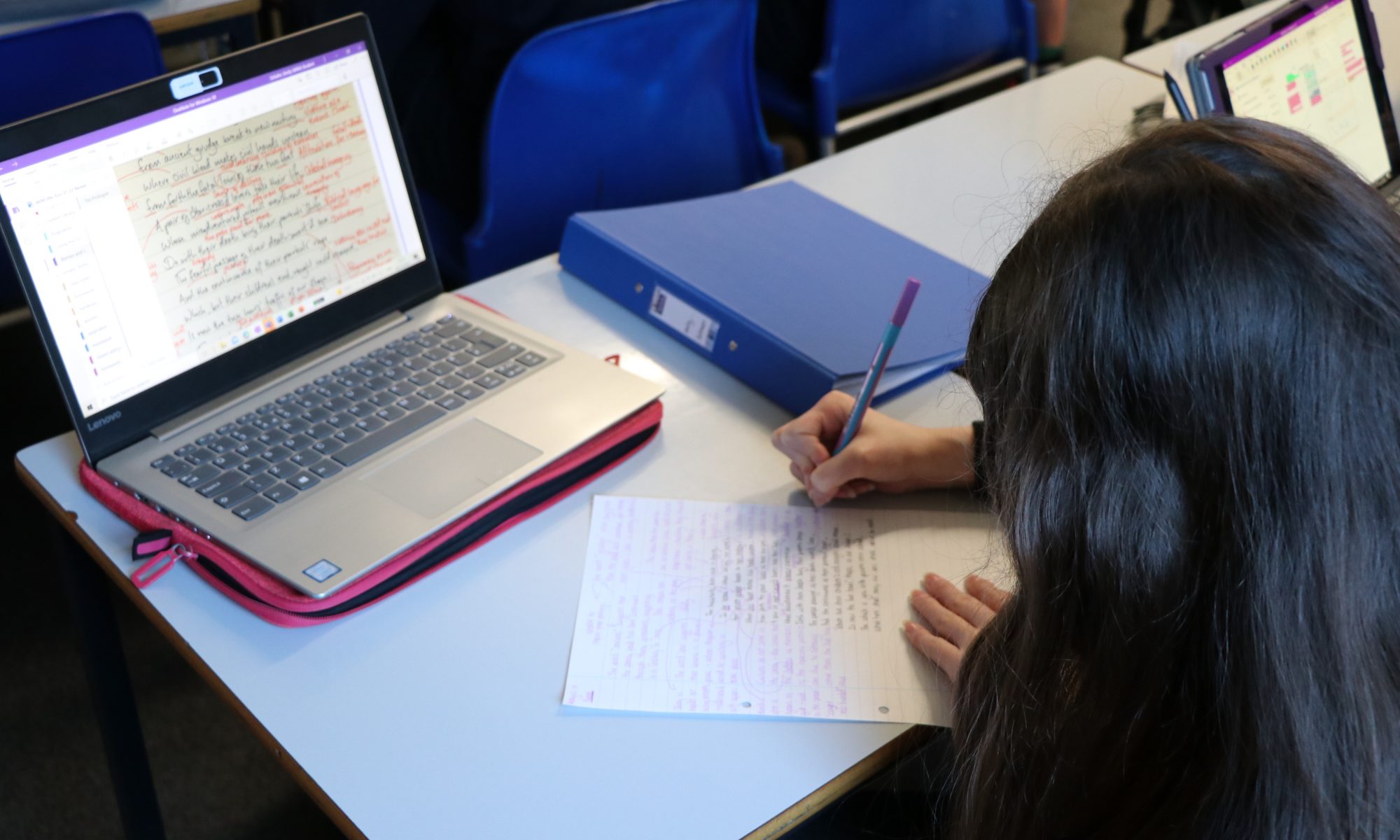

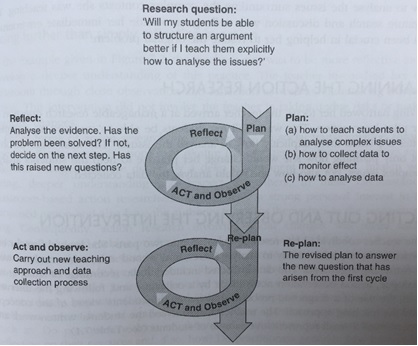

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing. Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.