Kira, Year 13, looks at the Turing test and how criticisms of it bring new ideas and concepts into the philosophy of mind.

As emerging areas of computer science such as Artificial Intelligence (AI) continue to grow, questions surrounding the possibility of a conscious computer are becoming more widely debated. Many AI researchers have the objective of creating Artificial General Intelligence: AI that has an intelligence, and potentially a consciousness, similar to humans. This has led many to speculate about the nature of an artificial mind, and an important question arises in the wake of this modern development and research: “Can computers think?”

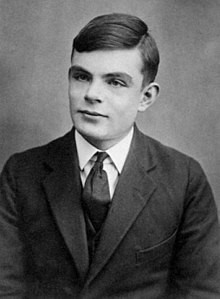

Decades before the development of AI as we know it today, Alan Turing attempted to answer this question in his 1950 paper Computing Machinery and Intelligence. He developed the famous Turing test as a way to evaluate the intelligence of a computer. Turing proposed a scenario in which a test subject would have two separate conversations: one with another human, and one with a machine designed to give human-like responses. These conversations would take place through a text-channel so the result would not be affected by the machine’s ability to render speech. The test subject would then be asked to determine which conversation took place with a machine. Turing argued that if they are unable to reliably distinguish the machine from the other human, then the machine has ‘passed the test’, and can be considered intelligent.

At the start of his essay, Turing specifies that he would not be answering “Can computers think?”, but a new question that he believed we are able to answer: “Are there imaginable digital computers which would do well in the imitation game?” However, Turing did believe that a computer which was able to succeed in ‘the imitation game’ could be considered intelligent in a similar way to a human. In this way, he followed a functionalist idea about the mind – identifying mental properties though mental functions, such as determining intelligence through the actions of a being, rather than some other intrinsic quality of a mental state.

Many scholars have criticised the Turing test, such as John Searle, who put forward the Chinese Room Argument and the idea of ‘strong AI’ to illustrate why he believed Turing’s ideas around intelligence to be false. The thought experiment looks at a situation where a computer is produced that behaves as though it understands Chinese. It is, therefore, able to communicate with a Chinese speaker and pass the Turing test, as it convinces the person that they are talking to another Chinese-speaking human. Searle then asks whether the machine really understands Chinese, or if it is merely simulating the ability to speak the language. The first scenario is what Searle calls ‘strong AI’, referring to the latter as ‘weak AI’.

In order to answer his question, Searle illustrates a situation in which an English-speaking human is placed in a room with a paper version of the computer program. This person, given sufficient time, could be handed a question written in Chinese and produce an answer by following the program’s instructions step-by-step, in much the same way as a computer does. Although this person is hence able to communicate with somebody speaking Chinese, they do not actually understand the conversation that is taking place, as they are simply following instructions. In the same way, a computer able to communicate in Chinese cannot be said to understand the language. Searle argues that without this understanding, a computer should not be described as ‘thinking’, and as a result should not be said to have a ‘mind’ or ‘intelligence’ in a remotely human way.

Searle’s argument has had a significant impact on the philosophy of mind and has come to be viewed as an important argument against functionalism. The thought experiment provides opposition to the idea that the mind is merely a machine and nothing more: if the mind were just a machine, it is theoretically possible to produce an artificial mind that is capable of perceiving and understanding all that it sees around it. According to Searle, this is not a possibility. However, many people disagree with this belief – particularly as technology develops ever further, the possibility of a true artificial mind seems more and more likely. Despite this, Searle’s Chinese Room argument continues to aid us in discussions around how we should define things such as intelligence, consciousness, and the mind.

In this way, both the Turing test and Searle’s critique of it shed new light onto long-standing philosophical problems surrounding the nature of the human mind. They serve to help bring together key areas of computer science and philosophy, encouraging a philosophical response to the modern world, as well as revealing how our new technologies can impact philosophy in new and exciting ways.