Taking a cue from Henri Bergson’s theory of time, Hafsa in Year 10 examines the science behind our sense that time speeds up when we are enjoying ourselves

Time is the most used noun in the English language and yet humans are still struggling to define it, with its complicated breadth and many interdimensional theories. We have all lived through the physical fractions of time like the incessant ticking of the second hand or the gradual change in season, however, do we experience it in this form? This is a question that requires the tools of both philosophy and science in order to reach a conclusion.

In scientific terms, time can be defined as ‘The progression of events from the past to the present into the future’. In other words, it can be seen as made up of the seconds, minutes, and hours that we observe in our day-to-day life. Think of time as a one directional arrow, it cannot be travelled across or reversed but only and forever moves forward.

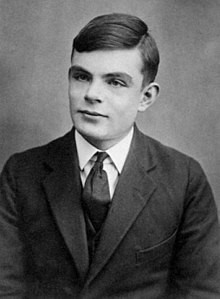

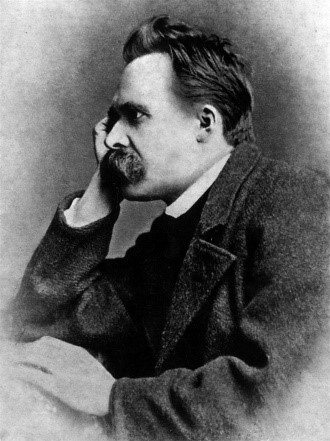

One philosophical theory would challenge such a definition of time. In the earliest part of the 20th century, the renowned philosopher Henri Bergson published his doctoral thesis, ‘Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness’, in which he explored his theory that humans experience time differently from this outwardly measurable sense. He suggested that as humans we divide time into separate spatial constructs such as seconds and minutes but do not really experience it in this form. If Bergson’s theory is right, our sense of time is really much more fluid than the scientific definition above suggests.

If we work from the inside out, we can explore the different areas of our lives which influence our perception of time. The first area is the biological make-up of our bodies. We all have circadian rhythms which are physical, mental, and behavioural changes that follow a twenty-four-hour cycle. This rhythm is present in most living things and is most commonly responsible for determining when we sleep and when we are awake.

These internal body clocks vary from person to person, some running slightly longer than twenty-four hours and some slightly less. Consequently, everyone’s internal sense of time differs, from when people fall asleep or wake up to how people feel at different points during the day.

But knowing that humans have slight differences in their circadian rhythms doesn’t fully explain how our sense of time differs from the scientific definition. After all, these circadian rhythms still follow a twenty-four-hour cycle just like a clock. If we look at the wider picture, what is going on around us greatly affects our sense of time. In other words, our circadian rhythms are subject to external stimuli.

Imagine you are doing something you love, completely engrossed in the activity, whether it be an art, a science, or just a leisurely pastime. You look at the clock after what feels like two minutes and realise that twenty have actually passed. The activity acts as the external stimulus and greatly affects your perception of time.

When engrossed in an activity you enjoy, your mind is fully focussed on it, meaning there is no time for it to wander and look at the clock. Research suggests that the pleasurable event boosts dopamine release which causes your circadian rhythm to run faster. Let’s take an interval of five minutes as a basis for this. In this interval, due to your internal body clock running faster you feel as though only two minutes have gone by; time feels like it has been contracted.

By contrast, when you are bored, less dopamine is released, slowing your circadian rhythm, meaning your subjective sense of time runs slower. If we use the same example, in an interval of five minutes, you feel as though ten minutes have gone by and time feels elongated. This biological process has the power to shape and fluidify our perception of time.

So, the next time someone says ‘Wow, time really does fly by when you’re having fun,’ remember that there is much more science and philosophy behind the phrase than they might realise!

Sources

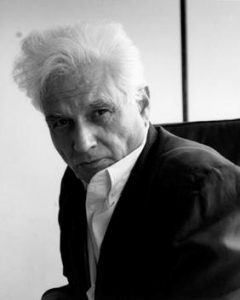

Deconstruction is a theory principally put forward in around the 1970s by a French philosopher named Derrida, who was a man known for his leftist political views and apparently supremely fashionable coats. His theory essentially concerns the dismantling of our excessive loyalty to any particular idea, allowing us to see the aspects of truth that might be buried in its opposite. Derrida believed that all of our thinking was riddled with an unjustified assumption of always privileging one thing over another; critically, this privileging involves a failure to see the full merits and value of the supposedly lesser part of the equation. His thesis can be applied to many age-old questions: take men and women for example; men have systematically been privileged for centuries over women (for no sensible reason) meaning that society has often undervalued or undermined the full value of women.

Deconstruction is a theory principally put forward in around the 1970s by a French philosopher named Derrida, who was a man known for his leftist political views and apparently supremely fashionable coats. His theory essentially concerns the dismantling of our excessive loyalty to any particular idea, allowing us to see the aspects of truth that might be buried in its opposite. Derrida believed that all of our thinking was riddled with an unjustified assumption of always privileging one thing over another; critically, this privileging involves a failure to see the full merits and value of the supposedly lesser part of the equation. His thesis can be applied to many age-old questions: take men and women for example; men have systematically been privileged for centuries over women (for no sensible reason) meaning that society has often undervalued or undermined the full value of women.