Georgia, Year 13, explores the British retreat at Dunkirk and argues that Hitler’s greatest mistake was at this point in the war.

Dunkirk was the climactic moment of one of the greatest military disasters in history. From May 26 to June 4, 1940, an army of more than three hundred thousand British soldiers were essentially chased off the mainland of Europe, reduced to an exhausted mob clinging to a fleet of rescue boats while leaving almost all of their weapons and equipment behind for the Germans to pick up. The British Army was crippled for months, and had the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy failed, Germany would have managed to conduct their own D-Day, giving Hitler the keys to London. Yet Dunkirk was a miracle, and not due to any tactical brilliance from the British.

Dunkirk was the climactic moment of one of the greatest military disasters in history. From May 26 to June 4, 1940, an army of more than three hundred thousand British soldiers were essentially chased off the mainland of Europe, reduced to an exhausted mob clinging to a fleet of rescue boats while leaving almost all of their weapons and equipment behind for the Germans to pick up. The British Army was crippled for months, and had the Royal Air Force and Royal Navy failed, Germany would have managed to conduct their own D-Day, giving Hitler the keys to London. Yet Dunkirk was a miracle, and not due to any tactical brilliance from the British.

In May 1940, Hitler was on track to a decisive victory. The bulk of the Allied armies were trapped in pockets along the French and Belgian coasts, with the Germans on three sides and the English Channel behind. With a justified lack of faith in their allies, Britain began planning to evacuate from the Channel ports. Though the French would partly blame their defeat on British treachery, the British were right. With the French armies outmanoeuvred and disintegrating, France was doomed. And really, so was the British Expeditionary Force. There were three hundred thousand soldiers to evacuate through a moderate-sized port whose docks were being destroyed by bombs and shells from the Luftwaffe. Britain would be lucky to evacuate a tenth of its army before the German tanks arrived.

Yet this is when the ‘miracle’ occurred. But the miracle did not come in the form of an ally at all. Instead, it came from the leader of the Nazis himself. On May 24th, Hitler and his high command hit the stop button. Much to their dissatisfaction, Hitler’s tank generals halted their panzer columns which could have very easily sliced like scalpels straight to Dunkirk. The Nazi’s plan now was for the Luftwaffe to pulverise the defenders until the slower-moving German infantry divisions caught up to finish the job. It remains unclear why Hitler issued the order. It is possible that he was worried that the terrain was too muddy for tanks, or perhaps he feared a French counterattack. Hitler later claimed, at the end of the war, that he had allowed the British Expeditionary Force to get away simply as a gesture of goodwill and to try to encourage Prime Minister Winston Churchill to make an agreement with Germany that would allow it to continue its occupation of Europe. Whatever the reason, while the Germans dithered, the British moved with a speed that Britain would rarely display again for the rest of the war.

Not just the Royal Navy was mobilised. From British ports sailed yachts, fishing boats and rowing boats; anything that could sail was pressed into service.

Under air and artillery fire, the motley fleet evacuated 338,226 soldiers. As for Britain betraying its allies, 139,997 of those men were French soldiers, along with Belgians and Poles. Even so, the evacuation was incomplete. Some 40,000 troops were captured by the Germans. The Scotsmen of the 51st Highland Division, trapped deep inside France, were encircled and captured by the 7th Panzer Division commanded by Erwin Rommel. The British Expeditionary Force did save most of its men, but almost all its equipment—from tanks and trucks to rifles—was left behind.

In spite of this, the British would and could continue to view the evacuation of Dunkirk as a victory. Indeed, the successful evacuation gave Britain a lifeline to continue the war. In June 1940, neither America nor the Soviets were at war with the Axis powers. With France gone, Britain, and its Commonwealth partners stood alone. Had Britain capitulated to Hitler or signed a compromise peace that left the Nazis in control of Europe, many Americans would have been dismayed—but not surprised.

Hitler’s greatest mistake was giving the British public enduring hope, ruling out any chance of them suing for peace. He gave them an endurance that was rewarded five years later on May 8, 1945, when Nazi Germany surrendered. A British writer, whose father fought at Dunkirk wrote that the British public were under no illusions after the evacuation. “If there was a Dunkirk spirit, it was because people understood perfectly well the full significance of the defeat but, in a rather British way, saw no point in dwelling on it. We were now alone. We’d pull through in the end. But it might be a long grim wait…”

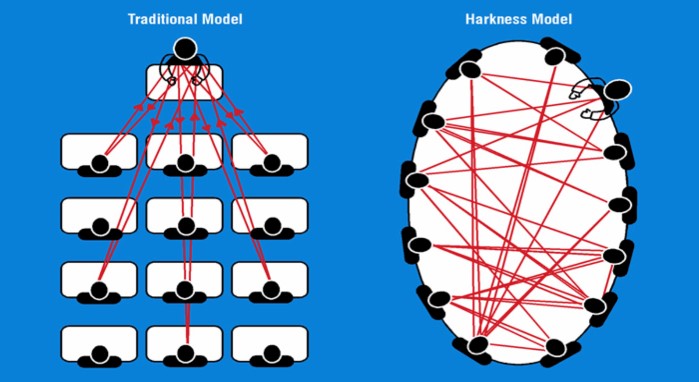

As the lessons progressed, I started enjoying this method of teaching as it allowed me to understand not only how each formula and rule had come to be, but also how to derive them and prove them myself – something which I find incredibly satisfying. I also particularly like the fact that a specific problem set will test me on many topics. This means that I am constantly practising every topic and so am less likely to forget it. Also, if I get stuck, I can easily move on to the next question.

As the lessons progressed, I started enjoying this method of teaching as it allowed me to understand not only how each formula and rule had come to be, but also how to derive them and prove them myself – something which I find incredibly satisfying. I also particularly like the fact that a specific problem set will test me on many topics. This means that I am constantly practising every topic and so am less likely to forget it. Also, if I get stuck, I can easily move on to the next question. Moreover, I very much enjoyed seeing how other people completed the questions as they would often have other methods, which I found far easier than the way I had used. The other benefit of the lesson being in more like a discussion is that it has often felt like having multiple teachers as my fellow class member have all been able to explain the topics to me. I have found this very useful as I am in a small class of only five however, I certainly think that the method would not work as well in larger classes.

Moreover, I very much enjoyed seeing how other people completed the questions as they would often have other methods, which I found far easier than the way I had used. The other benefit of the lesson being in more like a discussion is that it has often felt like having multiple teachers as my fellow class member have all been able to explain the topics to me. I have found this very useful as I am in a small class of only five however, I certainly think that the method would not work as well in larger classes.

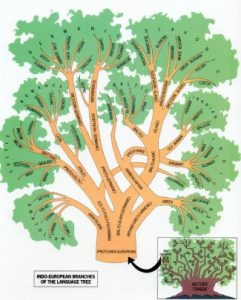

Both music and languages share the same building blocks as they are compositional. By this, I mean that they are both made of small parts that are meaningless alone but when combined can create something larger and meaningful.

Both music and languages share the same building blocks as they are compositional. By this, I mean that they are both made of small parts that are meaningless alone but when combined can create something larger and meaningful.

Distributed systems such as Bitcoin’s involve a negative externality that causes over investment in computer hardware as the expected marginal revenue from the individual miners is increasing with the amount of computing power that they individually have. Not only does this increase their own marginal cost but it increases the competition within the system and thus the cost is also increasing across the entire network. “Cetirus paribus” economic theory would suggest that in equilibrium all miners are inefficiently investing in hardware while receiving the same revenue that they would have had they not invested in the extra computing power. This behaviour is irrational as it is increasing the computing power across the entire network making it harder for them to succeed individually.

Distributed systems such as Bitcoin’s involve a negative externality that causes over investment in computer hardware as the expected marginal revenue from the individual miners is increasing with the amount of computing power that they individually have. Not only does this increase their own marginal cost but it increases the competition within the system and thus the cost is also increasing across the entire network. “Cetirus paribus” economic theory would suggest that in equilibrium all miners are inefficiently investing in hardware while receiving the same revenue that they would have had they not invested in the extra computing power. This behaviour is irrational as it is increasing the computing power across the entire network making it harder for them to succeed individually.

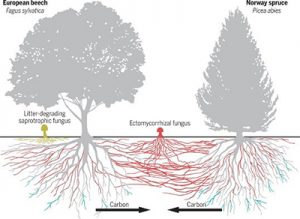

The driving researcher behind this work, Suzanne Simard, found that trees will help each other out when they’re in a bit of shade. She used carbon -14 trackers to monitor the movement of carbon from one tree to another. She found that the trees that grew in more light would send more carbon to the trees in shade, allowing them to photosynthesise more and so helping them provide food for themselves. At times when one tree had lost its leaves and so couldn’t photosynthesise as much, more carbon was sent to it from evergreen trees.

The driving researcher behind this work, Suzanne Simard, found that trees will help each other out when they’re in a bit of shade. She used carbon -14 trackers to monitor the movement of carbon from one tree to another. She found that the trees that grew in more light would send more carbon to the trees in shade, allowing them to photosynthesise more and so helping them provide food for themselves. At times when one tree had lost its leaves and so couldn’t photosynthesise as much, more carbon was sent to it from evergreen trees.

The day itself provided many opportunities for contemplative reflection, along with moments of pure fun and laughter. Our inaugural FeelGoodFest opened the event, a combination of effortlessmusic performances, beautiful poetry and heartfelt messages read aloud by students from all years. Particularly prominent in the morning’s proceedings was a lovely sense of friendship, provided not only by girls themselves thanking their friends for supporting them through thick and thin, but also through a heartwarming rendition of Carole King’s “You’ve got a friend” from Louisa and Anna (Year 13).

The day itself provided many opportunities for contemplative reflection, along with moments of pure fun and laughter. Our inaugural FeelGoodFest opened the event, a combination of effortlessmusic performances, beautiful poetry and heartfelt messages read aloud by students from all years. Particularly prominent in the morning’s proceedings was a lovely sense of friendship, provided not only by girls themselves thanking their friends for supporting them through thick and thin, but also through a heartwarming rendition of Carole King’s “You’ve got a friend” from Louisa and Anna (Year 13). A huge thanks must of course go to The Music Department, House Captains and Music Rep for the fabulous House Music event in the afternoon, which may or may not have included a whole-school dance-along to ABBA’s “Dancing Queen”, a firm Wimbledonian favourite. It was lovely to see students of all ages putting themselves forward to compete on behalf of their houses; a special mention goes to Meredith for winning the House Song category, and to Arnold for their win in the House Ensemble category.

A huge thanks must of course go to The Music Department, House Captains and Music Rep for the fabulous House Music event in the afternoon, which may or may not have included a whole-school dance-along to ABBA’s “Dancing Queen”, a firm Wimbledonian favourite. It was lovely to see students of all ages putting themselves forward to compete on behalf of their houses; a special mention goes to Meredith for winning the House Song category, and to Arnold for their win in the House Ensemble category.