Rachel Evans, Director of Digital Learning & Innovation, considers the impact of this year’s CPD on 21st Century Learning Design, evaluates the Social Robots project against the rubric and reflects on the value of this approach for teachers and students.

During the last term of this unprecedented school year, groups of teachers have been lifting their gaze beyond the challenge of the pandemic to reflect on the way we teach and learn. Since April, colleagues from the Junior and Senior Schools have been considering 21st Century Learning Design.(1) An academic research programme funded by Microsoft in 2010, the Innovative Teaching & Learning Research Project described and defined this pedagogical approach. Collaborative research was carried out across ten countries, with the Institute of Education in London as one of the partners. The outcome formed the basis of a framework for evaluating and designing schemes of work, and subsequently a programme of study for teachers.(2)

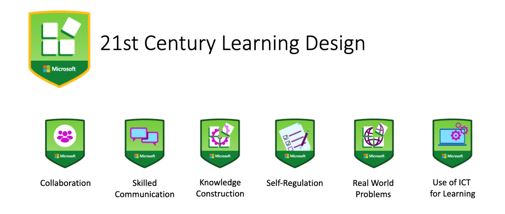

The six components of 21st Century Learning Design (21CLD)

21CLD is a lens through which we can view the planning and delivery of the curriculum – as broadly as across a whole topic, or down to the level of an activity within an individual lesson. The rubric-based approach across the six topic areas prompts teachers to think about how to effectively build skills which are not necessarily well understood or embedded by other pedagogical approaches. Whilst we may not accept the popular discourse about the necessity of ‘21st century skills’, the framework addresses the need for students to beopen to new ideas and voices, direct and be accountable for their own work, and conduct effective and meaningful collaboration: all skills which are valuable in a swiftly changing world.

A collaborative professional development opportunity

Teachers were assigned a module of the course to work through independently, and then came together in study groups to discuss the concepts and teach each other the module they had studied. This has proved an exciting way to learn about 21CLD and apply it to our own classroom practice. Mixed group discussions outside the silos of departments and key stages revealed how this pedagogy is applicable across different subject areas and age groups, and identified where there are connections with existing approaches, such as Kagan structures or Harkness method for communication and cooperation, and our STEAM+ interdisciplinary work.

The discursive approach allowed teachers to be candid about their experience. Delving into the detail of the rubrics brought self-reflection: one teacher saying “I thought we’d be brilliant at collaboration, but actually we often co-work rather than collaborate.” Teachers evaluated existing activities against the rubrics and considered how they could adjust their lesson plans and projects to create deeper engagement and more agency for their pupils, and substantive and meaningful work as a result. New plans for a science project about pollution and the revision of a history research topic are among the outcomes of this period of study. Junior School teachers investigated how different levels of the rubric might appropriate at different Key Stages: they plan to create examples of suitable activities to inform the planning of lessons which will develop skills over the pupil’s time in the infant and junior years.

The process was not uncritical, with much debate in both parts of the school around the knowledge construction module: balancing innovative approaches with the needs of the examination system and our own belief in the value of scholarship made for interesting conversations.

A real-life example of real-world problem-solving

As I studied the course myself and designed the programme for teachers, I evaluated one of my own projects.

The Social Robots Club, which the Head of Computer Science and I began two years ago, is an excellent example of real-world problem solving and collaboration within the 21CLD framework, which has arisen organically through the interests of a group of Year 10 students. You can read about their work in this week’s WimTeach[link], where the girls have written about their project and experiences.

The purpose of the club was to experiment with our Miro-E robots (3), in order to plan their inclusion in the curriculum. It is the students who have driven the project forward. From our early brainstorming about uses for the robots, they chose a goal, defined their project and set to work. How does this activity measure up as an example of 21st century learning?

Collaboration

Students work as a team, assigning roles for each task, and making their own decisions about the process and product. The work is interdependent – for instance, dividing up the writing of code into segments which will be later combined.

Skilled communication

Students have produced presentations for Junior school staff, a lesson plan for Year 5 pupils, surveys and a leaflet for parents and an assembly for the school community. They carried out academic research including writing to the authors of papers with further queries.

Knowledge construction

We had never used such sophisticated robotics at school previously, but the group are already competent coders, so are applying their knowledge. Research for the project has covered psychology, pedagogy and computer science – certainly interdisciplinary.

Self-regulation

This group of students have worked on this project for a year and are clear about their aims, and what success will look like. They plan their own work – in fact, Mr Richardson and I joke that we are superfluous! – but we are there, of course, to offer feedback and guidance to help the team make progress when the project stalls.

Real-world problem-solving and innovation

The project is problem solving on a macro and micro level. The real-world problem is about improving reading progress for primary age children, but every week is micro problem-solving as we navigate a new and unfamiliar coding interface and sophisticated but temperamental robots. The project will have a real-world implementation when the robots are used by Year 1 next year.

Use of ICT for Learning

Technology is crucial to the project, obviously, but most significantly, we will create a product for authentic users – a robot creature who will respond with encouragement to a child reading – a great deal of code will lie behind those simulated behaviours!

The benefits of 21st Century Learning Design

On a practical level, 21CLD offers teachers tools for creating learning activities which promote skills that we would all agree are essential for study, work and life – to communicate clearly, collaborate well and solve problems. When combined with our emphasis on scholarship and our interdisciplinary STEAM+ philosophy, I find three further important outcomes:

Building knowledge and appreciating complexity

In a fast-paced world, the experience of going deeply into a topic or project for a sustained period will develop sound knowledge and critical thinking skills. Grappling with complexity brings an appreciation that not all problems are solved or ideas best expressed with a sound-bite response. All fields of study are rich with nuance once we go beyond the superficial.

Identifying unknowns, living with uncertainty and resilience

The deeper students go into complexity, detail and a wealth of knowledge, the more aware they become of what is unknown, either to themselves or to others. In a year which has been filled with uncertainty, an awareness that what we understand of the world is not fixed or fully known is, at first, unsettling. Sitting with that uncertainty – whether academic or otherwise – can build resilience. As the students write in WimLearn this week, persevering through difficulty brings its own joys.

Curiosity and exploration

Having appreciated complexity and experienced uncertainty, where do we go next? We have the answer enshrined within our school aims: Nurturing curiosity, scholarship and a sense of wonder. To achieve sufficient mastery of an area of study that we can begin to push at the boundaries is where exploration and innovation happens; or, as we wrote at the start of this year (4), in the spaces and connections between traditional subject areas with our STEAM+ philosophy. Depth of study, knowledge and skill is a firm foundation for exploration.

In conclusion, the exploration of this course on 21st century learning design has been incredibly valuable. At a time when we have been caught in the weeds of logistics and change, the programme of study and our collaborative approach has opened up big ideas and new conversations between teachers, which we will continue to explore next year. This feels like the start of a new conversation about the way we use technology in the classroom.

References

(1) 21st Century Learning Design, Microsoft Educator Center, https://education.microsoft.com/en-us/learningPath/e9a3beec

(2) You can read the original research papers and other references here, within the Microsoft CPD course. https://onedrive.live.com/redir?resid=91F4E618548FC604%21300&authkey=%21AOE-MnST_ZCMc1Q&page=View&wd=target%28Embedding%2021CLD%20in%20practice.one%7C2989f197-22e1-42a9-b2d5-2a71628825c1%2F21CLD%20Readings%7Ce58d3c47-38fa-47da-9077-18571f525580%2F%29

(3) Miro-E are programmable social robots designed for us in schools. http://consequentialrobotics.com/miroe

(4) Bristow & Pett, STEAM+, http://whs-blogs.co.uk/teaching/steam-2/, September 2020