Lilly (Y11), discusses the importance of honesty in law and whether the practice of Law and the Justice System needs honesty to function.

When considering this question, it is tempting to immediately think of the skilful, yet exploitative nature in which lawyers can bend any law or lunge into any loophole which will win their case, thus concluding that honesty most definitely does not fit into law. This narrative has been one that is heard in stories stretching back centuries; if we stretch back three, to the words of 18th century poet John Gay, he describes this as follows:

I know you lawyers can with ease,

Twist words and meanings as you please;

That language, by your skill made pliant,

Will bend to favour every client;

That ’tis the fee directs the sense,

To make out either side’s pretence.

Now, it is incorrect to say that there is no truth in this. If we think about why lawyers are hired in the first place, it is obviously to find ways in which the law can be used to favour their client. It is doubtful that many people would hire a lawyer and tell them to find whatever they believed to be the most honest plan of action to take, rather than what will let them walk free. In other words, a lawyer’s job in essence is to manipulate the legal terms and conditions in order to present a client who seems like an innocent person in front of a jury, but perhaps looks more like a thief when they close the doors of the court behind them.

The law is a set of codes, and the program that the codes feed in to allows for our society to be regulated and run smoothly.

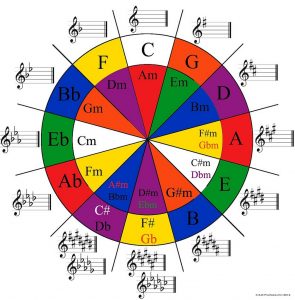

To really understand this question, we have to strip the very concept of law back to its basics. The Oxford Dictionary recognises law as “the system of rules which a particular country or community recognises as regulating the actions of its members and which it may enforce by the imposition of penalties.” In essence, the law is a set of codes, and the program that the codes feed in to allows for our society to be regulated and run smoothly. This view of society as fairly binary, (right or wrong), does not allow any scope for honesty, therefore, it could be said that the law is much like a computer program with lawyers being the coders, operating the whole show.

However, with the risk of sounding like we live in some sort of dystopian novel controlled by an IT department of lawyers, lets look at why this idea is flawed. This stripped-down view of law to its basic components is very different to our unfortunately much less simple reality, where honesty must have a purpose in law. If you cut right to the heart of law, you see that honesty is in fact an integral part of its composition. It’s no mistake that one swears to tell “the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth” at a trial. This reflects not just the presence, but the necessity of truth in law.

Yet even so, a necessity for honesty doesn’t necessarily translate to there being a guarantee of honesty. Every single human is dishonest at some point (if not many points) during their lives. On the whole, this dishonesty manifests itself in the form of white lies, which are, on the whole, harmless. It is only for a smaller portion of society that these present themselves as serious crimes. But, this is the important part. The very system of law only works when assuming that human beings are honest most of the time. If we were the opposite, i.e. dishonest most of the time, the system of law as we know it would not be able to function, and instead we would probably be living under a system where the means of control were strictly military. But conversely, if human beings were intrinsically honest, this would mean that we wouldn’t need law at all, and would probably live more in something similar to the computer analogy mentioned earlier. The assumption that we are honest most of the time means that the law functions by the system of proving someone to be dishonest, reflected in the well-known phrase “innocent until proven guilty”. Can you imagine if humans were recognised to be dishonest most of the time by the law? This would not only blur the lines as to if a law that was made was good or bad, but also make it incredibly hard to distinguish between a law being created to prosecute or persecute (which would probably result in martial law).

If human beings were intrinsically honest, this would mean that we wouldn’t need law at all.

In short, there isn’t a straightforward answer to this question. Many ideas have been suggested in disagreement with honesty’s place in law, due to the self-interested, survivalist nature of humans, which determines that even if honesty did have a place in law, this honesty is easily undermined by the fact that humans are driven by self-preservation, which usually doesn’t coincide with being completely honest. But even so, it is undebatable that the level in which we regard honesty’s significance in law has a huge influence on our society.