With ‘slowing down’ a key part of our wellbeing strategy of ‘Strong Body, Strong Mind’, our Director of Studies, Suzy Pett, looks at why slowing down is fundamental from an educational perspective, too.

So often, the watch words of classroom teaching are ‘pace’ and ‘rapid progress’. I’m used to scribbling down these words during lesson observations, with a reassuring sense that I’m seeing a good thing going on. And I am. We want lessons to be buzzy, with students energised and on their toes. We want them to make quick gains in their studies. But is it more complex than this?

The more I think about it, the more I am convinced that ‘slow and deep’ should be the mantra for great teaching and learning. I’m not suggesting that lessons become sluggish. But, we need to jettison the idea that progress can happen before our very eyes. And, with our young people acclimatised to instant online communication, now more than ever do we need our classrooms – virtual or otherwise – to be havens of slow learning and deep thinking. Not only is this a respite from an increasingly frenetic world, but it is how students develop the neural networks to think in a deeply critical and divergent way.

What I love most in in the classroom is witnessing the unfurling of students’ ideas. This takes time. I’m not looking for instant answers or quick, superficial responses. I cherish the eeking out of a thought from an uncertain learner, or hearing a daring student unpack the bold logic of her response. Unlike social media, the classroom is not awash with snappy soundbites, but with slow, deep questioning and considered voices. As much as pacey Q&A might get the learning off to a roaring start, lessons should also be filled with gaps, pauses and waiting. You wouldn’t rush the punch line of a joke. So, it’s the silence after posing a question that has the impact: it gifts the students the time for deep thinking. In lessons, we don’t rattle along the tracks; we stop, turn around and change direction. We revisit ideas, and circle back on what needs further exploration. This journey might feel slower, but learning isn’t like a train timetable.

But what does cognitive science say about slow learning? Studies show that learning deeply means learning slowly.[1] I’m as guilty as anyone at feeling buoyed by a gleaming set of student essays about the poem I have just taught. But don’t be duped by this fools’ gold. Immediate mastery is an illusion. Quick-gained success only has short term benefits. Instead, learning that lasts is slow in the making. It requires spaced practice, regularly returning to that learning at later intervals. The struggle of recalling half-forgotten ideas from the murky depths of our brains helps them stick in the long-term memory. But this happens over time and there is no shortcut.

Interleaving topics also helps with this slow learning. Rather than ploughing through a block of learning, carefully weaving in different but complimentary topics does wonders. The cognitive dissonance created as students toggle between them increases their conceptual understanding. By learning these topics aside each other, students’ brains are working out the nuances of their similarities and differences. The friction – or ease – with which they make connections allows learners to arrange their thoughts into a more complex and broad network of ideas. It will feel slower and harder, but it will be worth it for the more flexible connections of knowledge in the brain. It is with flexible neural networks that our students can problem solve, be creative, and make cognitive leaps as new ideas come together for a ‘eureka’ moment.

Amidst the complexity of the 21st century, these skills are at a premium. With a surfeit of information bombarding us and our students from digital pop-ups, social media and 24 hour news, the danger is we seek the quick, easy-to-process sources.[2] This is a cognitive and cultural short circuit, with far reaching consequences for the individual’s capacity for critical thinking. With the continual rapid intake of ideas, the fear is a rudderlessness of thought for our young people.[3]

And yet, peek inside our classrooms, and you will see the antidote to this in our deep, slow teaching and learning.

Sources:

[1] David Epstein, Range (London: Macmillan, 2019), p. 97.

[2] Maryanne Wolf, Reader, Come Home (New York: HarperCollins, 2018), p. 12.

[3] Ibid. p. 63.

Music is everywhere. Wherever we go, no matter where, there will be some sort of tune or melody coming from someplace or another. Virtually all species, from the most primitive to the most modern, make music. In tune or not, our species sing and play, or clap and drum. Music is a cardinal aspect of our lives. The human brain and nervous system are programmed to distinguish music, rhythm and tones from noise and other sounds. Is this a biological accident, or does it serve a purpose? There might be no definite answer, but one could suggest from studies that music may enhance human health.

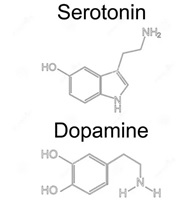

Music is everywhere. Wherever we go, no matter where, there will be some sort of tune or melody coming from someplace or another. Virtually all species, from the most primitive to the most modern, make music. In tune or not, our species sing and play, or clap and drum. Music is a cardinal aspect of our lives. The human brain and nervous system are programmed to distinguish music, rhythm and tones from noise and other sounds. Is this a biological accident, or does it serve a purpose? There might be no definite answer, but one could suggest from studies that music may enhance human health. As well as calming, and being a stress relief, music can be a source of happiness. It has the ability to make people of all ages feel cheerful and energetic and could even lift the mood of people with depressive illnesses. A recent study

As well as calming, and being a stress relief, music can be a source of happiness. It has the ability to make people of all ages feel cheerful and energetic and could even lift the mood of people with depressive illnesses. A recent study

When someone says asylum in the context of psychology, what do you immediately think of? I can safely assume most readers are picturing haunted Victorian buildings, animalistic patients rocking in corners and scenes of general inhumanity and cruelty. However, asylum has another meaning in our culture. Asylum, when referring to refugees, can mean sanctuary, hope and care. Increasingly people are exploring this original concept of asylum, and whether we, in a time when mental illness is more prevalent than ever, can reclaim the asylum? Or is it, and institutional in general, confined to history?

When someone says asylum in the context of psychology, what do you immediately think of? I can safely assume most readers are picturing haunted Victorian buildings, animalistic patients rocking in corners and scenes of general inhumanity and cruelty. However, asylum has another meaning in our culture. Asylum, when referring to refugees, can mean sanctuary, hope and care. Increasingly people are exploring this original concept of asylum, and whether we, in a time when mental illness is more prevalent than ever, can reclaim the asylum? Or is it, and institutional in general, confined to history?