Suzanne East, Head of Year 12 at WHS, looks at how listening can empower us as teachers and learners.

I am a talker, and I suspect that is true of many teachers. We get a buzz from sharing our passions for our subject, from explaining and answering questions and from solving problems. But increasingly my attention has been drawn to the importance of listening as a vital way to genuinely shift our focus away from ourselves, our opinions and assumptions; forcing us to notice what is really happening for our students, what they are learning and the journey they are making as they engage with the information we are presenting.

During this time of lock down this has been brought into sharper focus as we realise what we miss by not being able to see and hear our pupils in person. I think many of us have experienced that unsettling feeling of talking into the void, calling out for any pupil to respond! This has added to my intention to ensure that I bring good quality listening to my school life once we return.

Concerns about the quality of listening may be a reaction to the Twitter generation which seems to demand that we constantly project our thoughts and ideas out into the world – this demand to be seen and heard where perhaps nobody is doing the listening. But we have long been aware that it is easier to notice and respond to the louder and more obvious messages that can be presented by students. Susan Cain’s “Quiet: The power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking” reminded us of what we may miss if we don’t stop to make sure that all voices are heard, and of our obligation as teachers to ensure that no one is overlooked.

Attending mindfulness sessions with MiSP and again in courses with the Positive Group, I started to realise the difference between my usual listening style and what really thoughtful and attentive listening can be. The requirement to stop and to observe your surroundings is closely linked to the need to listen as well. To stop sending messages out and to take time to notice what is actually being said. Practising this stillness and trying to observe the moment was both a relief and a revelation. Accepting that I don’t have to respond to everything straight away, fighting the urge to jump in when listening even to a simple story, and noticing my instinct to mould what I hear to fit my own experience and expectation was a real eye opener.

One listening activity many of you may have tried is that of working in pairs to sit silently for between 1 to 3 minutes whilst the partner describes a situation, perhaps a simple event like a holiday or a more emotional experience such as a recent frustration or disappointment. In either case it is revealing to notice the desire as a listener to interrupt, join in and comment, rather than allowing the story to be and remain that of the storyteller. Feeling that listening to each other is a skill our girls will also need to develop, and we have tried this with Y12.

We asked them to sit back to back in pairs to listen for one minute to their partner and then to repeat back what they had heard. Giving time to listen to the end of the story and then telling the account back allows a sense of mutual understanding to grow and holds a mirror to the mistakes we often make in our everyday interactions. By actually doing this exercise the girls were able to start to experience this for themselves and to acknowledge their own behaviours. We know that many friendship issues arise from not listening honestly to each other and the damage done by quick reactions to a message on social media which can then take months of unpicking to repair the hurt caused.

Encouraging girls to listen fully to the whole story, to think before they act, and to go back and check with each other to see if they have understood correctly, are all useful tools in diffusing potentially viral misunderstandings. Despite all our efforts to be more inclusive and to accept diversity, we also live in a social media age which encourages swift reactions with a quick “like” or “dislike”. It is our responsibility as educators to highlight the potentially damaging impact of this and to explore the advantage of allowing space to consider the nuanced motivations that contribute to individual actions and decisions. We explored this further with our Sixth Form using the three chairs activity, in which the same situation was described from the perspective of the protagonist, victim and a fly on the wall. In my group the fairly trivial example of Horrid Henry and Perfect Peter led to a surprisingly rich discussion on the different motivations for bullying.

We want our students to be able to open up to us and we want to help them to live happier and more fulfilled lives. From our greater age, we can look back at the challenges of teenage life and see where we could have done it better, but that is not what any student wants to hear; we have to be careful to make sure the conversation remains focussed on the student and not on us or our ability to problem solve quickly.

Neuroscientist Sarah Jayne-Blackmore has spoken and written many times on the nature of the adolescent brain and reasons why it leads to greater risk-taking behaviour, and how this behaviour is significantly influenced by peer group approval. We want to influence our students and encourage them to make what we consider the best decisions, but the evidence suggests that they are not going to hear us unless we really take time to listen and understand what is important to them. We allocate time to one to one conversations with form tutors in the sixth form, but successfully managing these is not easy and tutors need to be skilful in creating a situation of trust in which a student can really open up. Mark Wilmore, one of our tutors with many years of experience as a Samaritan, training as a Counsellor and also as a sixth form tutor, shared his top tips for these conversations:

- Check in & boundaries

- Non-verbal communication

- Listen ‘actively’

- Have an agenda

- Try to avoid closed questions

- Use challenge where appropriate

- Feedback

- Set targets

- Keep a written record

- Follow up

Making it obvious to the student that these conversations are important – that they deserve proper time and attention and that we are genuinely listening to their experience and their story – are vital in building a successful relationship. Body language and preparation will tell the student far more than words, so making sure you have time to genuinely be there for them is vital, as they will be quick to assume that we are not really interested and then any words of wisdom we have will fall on stony ground.

It is also an important part of a student’s development to struggle and to find their own solutions to problems. We need to empower them with the confidence to know that they can make the change for themselves and that they have the skills that they will need. Rachel Simmonds says in Enough As She Is that “suffering is key to our children’s learning” and “that the price of some of our most important life lessons-the ones that make us wiser, tougher, and more capable-is pain, even heart-break” (Simmonds p200). This isn’t to leave them on their own, but to be with them and give them space to sound out their own solutions so that next time they know they will manage better.

In PSHE earlier this year we invited the Samaritans in to talk with Y12. Hearing the accounts of these masters of listening without judgement, the ones that those who are feeling most isolated and rejected turn to were truly inspiring. But they emphasised that the skills of listening were something that we should all practise in our relationships to help avoid people becoming isolated in the first place. Their campaign Shush “wants to encourage people to listen to the really important things their friends, family and colleagues need to tell them, and to devote some time and attention to being better listeners” (Samaritans). This was a powerful session, which left us all awed by the potential impact each one of us can make by just taking the time to stop and listen and allowing others to be heard.

Bibliography

Blackmore, Sarah-Jayne https://www.edge.org/conversation/sarah_jayne_blakemore-sarah-jayne-blakemore-the-teenagers-sense-of-social-self

Cain, Susan (2012) Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a world that Can’t Stop Talking, Crown Publishing Group/Random House, Inc.

Mindfulness for schools https://mindfulnessinschools.org/mindfulness-in-education/

Positive group https://www.positivegroup.org/positive-for-schools/

Simmons, Rachel (2018) “We Can’t Give Our Children What We Don’t Have” in Enough As She Is Harper Collins, New York.

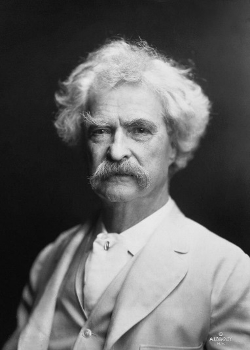

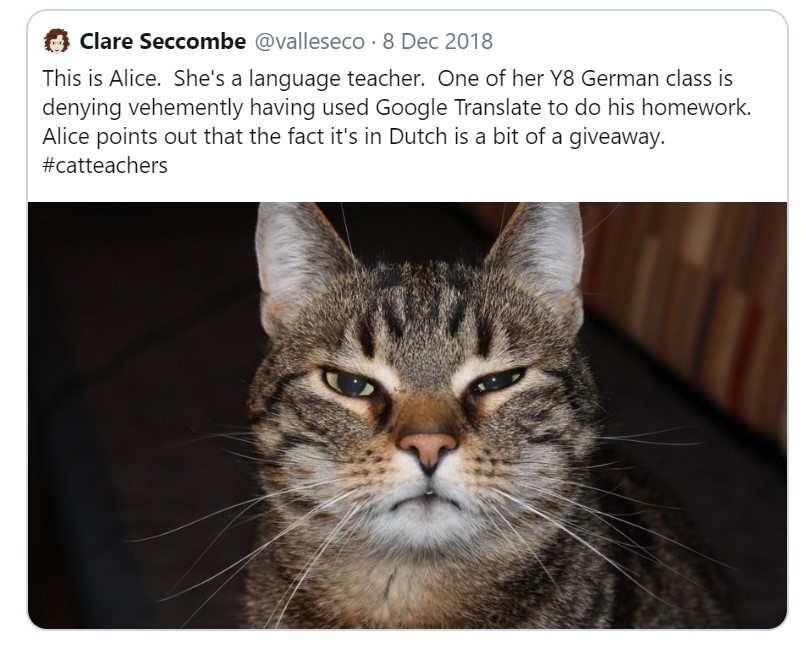

When a playwright is asked ‘what makes me qualified to write this play?’ the immediate assumption can be that our work should be in some ways autobiographical in order to be ‘authentic’ and ‘truthful’. One of the most oft-quoted aphorisms in creative writing is a comment attributed to Mark Twain, “Write what you know.”

When a playwright is asked ‘what makes me qualified to write this play?’ the immediate assumption can be that our work should be in some ways autobiographical in order to be ‘authentic’ and ‘truthful’. One of the most oft-quoted aphorisms in creative writing is a comment attributed to Mark Twain, “Write what you know.”

In Year 6, our pupils study navigational skills in a woodland setting, in order to learn how to use compasses and read maps. These are skills that could be potentially get lost in the high-tech world our children are being brought up in. When learning about directions on a compass, one misconception emerged when a pupil suggested that North is always dictated by the direction of the wind! Even if she never uses a compass again in her life, she has been afforded a valuable learning opportunity.

In Year 6, our pupils study navigational skills in a woodland setting, in order to learn how to use compasses and read maps. These are skills that could be potentially get lost in the high-tech world our children are being brought up in. When learning about directions on a compass, one misconception emerged when a pupil suggested that North is always dictated by the direction of the wind! Even if she never uses a compass again in her life, she has been afforded a valuable learning opportunity. In Reception, these experiences are focused on inviting the pupils to be a part of their environment, to observe and respect what they can see, hear and feel. Using stories as a starting point, we connect with nature and encourage the girls to lead the learning experience. However, the most fun our girls have had was splashing in the puddles on their way into the forest! These opportunities provide the foundation for these young learners to grow and to develop as they move through the Junior School.

In Reception, these experiences are focused on inviting the pupils to be a part of their environment, to observe and respect what they can see, hear and feel. Using stories as a starting point, we connect with nature and encourage the girls to lead the learning experience. However, the most fun our girls have had was splashing in the puddles on their way into the forest! These opportunities provide the foundation for these young learners to grow and to develop as they move through the Junior School. Year 1 pupils have used free play to explore the woods, making wind chimes and mud cakes, whilst coming across many mini beasts to identify. In the outdoors, nature is in control. Although you can predict what the weather is going to do, you can’t predict what children will learn the most from in the natural classroom you’ve created. This is the beauty of outdoor education.

Year 1 pupils have used free play to explore the woods, making wind chimes and mud cakes, whilst coming across many mini beasts to identify. In the outdoors, nature is in control. Although you can predict what the weather is going to do, you can’t predict what children will learn the most from in the natural classroom you’ve created. This is the beauty of outdoor education.