Mr Rob Dunn, Head of Physics at Wimbledon High School, known to some as Fyro, the half-Orc Bard, discusses the place that table-top RPGs (role-playing games) might have in schools generally and in supporting learning in the classroom.

I am proud to say, I’m a nerd. In the past, that term was defined as someone who loves ‘uncool’ things such as Physics, Maths, Computers, and of course Dungeons and Dragons. But now, thanks in part to the popularity of The Big Bang Theory, The Witcher, and Stranger Things, the nerd has become cool, and along with them, everything that they were associated with.

As educators, it can often seem that we are competing for the attention of our students with the influences of pop-culture, so when pop-culture directs their attention to us it would be missed opportunity not to capitalise on it.

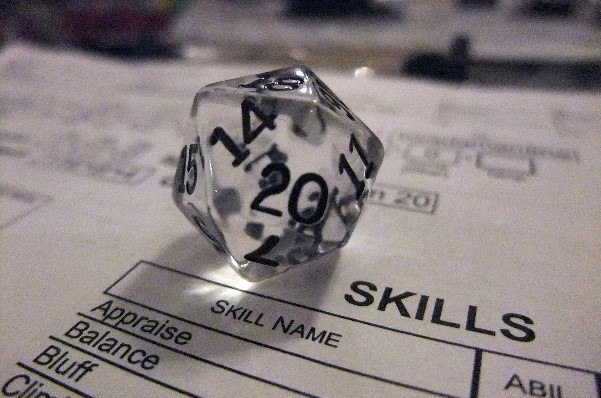

For those readers who are unfamiliar with how table-top role-playing games (RPGs) work, they are simply a structure and set of rules that allow players a space to live in a shared imagination. This shared imaginary world is curated by one player known as the ‘Game Master’ or GM. For beginners, this world usually based on published source material, such as the ever-popular Forgotten Realms of Wizard of the Coast’s Dungeons and Dragons. However, once the basics of gameplay have been grasped the only limit is your imagination, or perhaps a handful of dice that seem determined to kill you!

You play all sat around a table together with the GM at the head. You’ll debate with your fellow adventurers over who needs to do what next to solve the seemingly endless torrent of problems that are being thrown at you, you’ll be running a constant string of probabilities through your head as you try to decide if the chance is glory is worth the risk of another throw of the dice, you’ll socialise with your friends, and above all, you’ll share in the telling of a story that is unique to you and your group.

Playing RPGs develops a player’s imagination, creativity, storytelling, confidence, and the depth of social interactions. These are all skills that as a teacher I long for my students to show in the classroom, regardless of the curriculum I am trying to teach. In Physics particularly being able to think outside the box to solve a tricky exam question is often the difference between an A and A*, so if we can teach just a little of that in an activity that the students voluntarily commit to, then to me that is a ‘critical hit!’

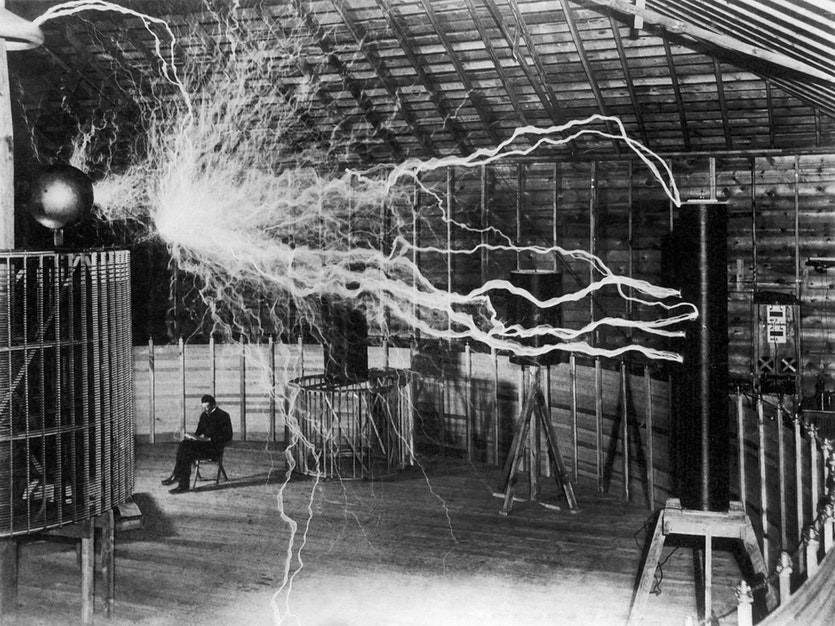

Other topics we teach in Physics can be very abstract and difficult for some students to engage with. Perhaps if we could immerse the students 1880s New York and the electrifying battle between Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison, we might make the often opaque world of transformers a little less mystifying.

I wonder if this might work in other subjects as well. An English department might base a game in the world of the text they are studying, or a history lesson might take the students through the dizzying streets of medieval London. In Politics, students might develop their own systems of government for the world in which they’re playing, while the geographers draw topologically accurate maps that they can use in games that display the different land and rock formations they have studied. In Music, the composer Nobuo Uematsu, who wrote the music for the Final Fantasy game series, is a set composer at A Level, enabling pupils to study the link between music and gaming.

At Wimbledon High School we have a growing extracurricular Dungeon’s and Dragons club with 3 different campaigns in play, some written and run by the students themselves, and one even counting teachers among the party of adventures. We have a great time playing each Friday lunchtime, and as I head to afternoon lessons I can’t help but wonder if a little bit of that style of fun and social learning can find a place in my next lesson.

So I’m calling on teachers everywhere, join me at the table and let’s ‘roll initiative’.

– a text message, a web search and an email all have a carbon footprint;

– a text message, a web search and an email all have a carbon footprint;