Ruby L, Deputy Head Girl, explores the significance of maps within literature, and how they help imaginatively guide both readers and writers.

Many famous literary works started off as a blank piece of paper and an idea for a fictional world. J.R.R. Tolkien produced three maps [1] and six hundred place names for his ‘Lord of the Rings’ trilogy, which became one of the bestselling series in history with over 150 million copies sold worldwide [2]. He is one of many successful authors to utilise the practice of cartography in the establishment of a fantasy land, along with Robert Louis Stevenson, who wrote ‘Treasure Island’ with the inspiration of a hand-drawn map; and C.S. Lewis, who invented Narnia. But why is this technique so popular and why does it make for more developed novels and fruitful book sales?

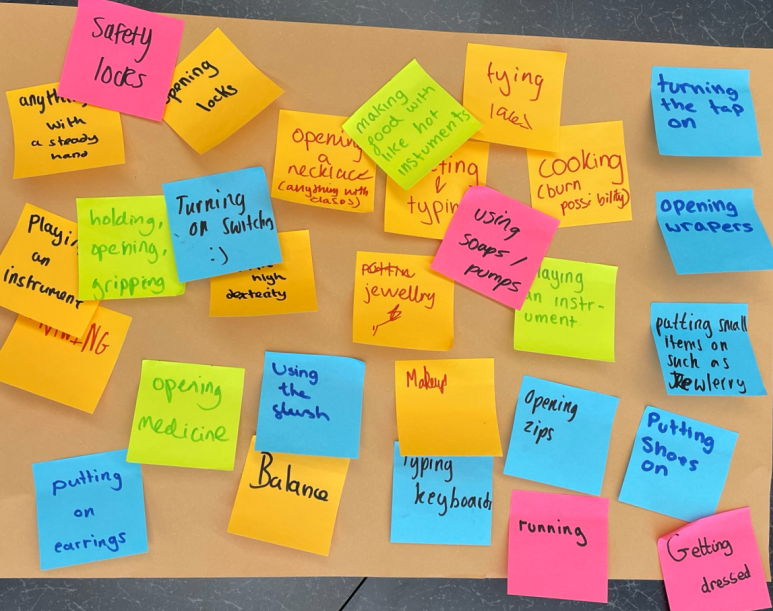

As Holly Lisle reveals, the process of literary map-making is an extensive and varied one. Authors generally depict a country or full land map instead of a city or street to generate a full view of the world they are creating and its geography. Once borders have been established, the addition of features such as mountain ranges, forests and cities fill the world with purpose and start to create a realistic-looking artefact. Mistakes made can also be of benefit to the plot and narrative. For example, if extra lines are drawn accidentally or a town has been placed far from any others, there is space for artistic license to make these into a story. If there is an abandoned trail it could have been deserted after a guerrilla warfare group used it in an ambush, and the isolated town could be used to excommunicate criminals as punishment in the country’s justice system [3].

But why wouldn’t the author simply write and skip this sketching? The answer is simple: this physical expression of the world inside the author’s head is invaluable when delving deeper into the story’s background. The writer can use their map to discover more about the land they have pictured, which is the main luxury of using cartography to compliment literature. Even a simple structure like the borders of the land probes into why that line was laid in that precise place. Was there dispute or war over territory? How are foreign relations between this country and its neighbour, and how does this impact the everyday lives of the citizens? Does a potential lack of security give rise to a totalitarian state in which inhabitants cannot cross the threshold to leave? Questions like these help the author to contextualise the history of the world that they are creating, which makes for a more three-dimensional setting. It helps us to understand their message in relation to their world’s history and landscape (political and social as well as physical) and in this respect, cartography is undoubtably important for the production of a fantasy world from an author’s perspective.

With the market for novels becoming more competitive, readers gravitate towards stories with an easily visualisable world and deeply considered, nuanced characters. Although there are many techniques which can achieve this, mapping is a simple way to produce ‘evidence’ for the fictional land to exist as they imply the realism of the author’s creation [4]. It adds another layer of credibility to the novel as we want to believe in what has been put in front of us. By human nature we are inclined to wish to read for escapism and suspension of disbelief is a huge part of what draws us into the narrative, so producing artefacts becomes very useful. This fact is what makes book sales soar for fantasy novels as they carry us away from the sometimes mundane real world. The illusion of reliability from a seemingly genuine source encourages us to engage with the text more deeply.

J.R.R. Tolkien’s work is a clear example of how mapmaking benefits both the author and reader in a fictional tale. He wrote in a letter to the novelist Naomi Mitchinson in 1954 that: ‘I wisely started with a map and made the story fit (generally with meticulous care for distances). The other way about lands one in confusions and impossibilities, and in any case, it is weary work to compose a map from a story.’ [1] Tolkien decided to come up with detailed maps depicting what would become ‘middle-earth’ and even chose to invent detailed languages and names before creating a plot. Based on his remarks, we can see that having a map before a narrative is not a defect but a delight, as successful exploration of possible characters and storylines can only come from detailed research and prior thought as to the setting. Not only was Tolkien’s cartography useful for him to devise a plot, it was widely appreciated by readers of his books worldwide. Literary critic Shippey writes that his maps are “extraordinarily useful to fantasy, weighing it down as they do with repeated implicit assurances of the existence of the things they label, and of course of their nature and history too” [1].

It is no wonder that fantasy books containing careful cartography are so popular and successful, then. They are sure to thrive as long as humans continue to need exploration and escapism.

Bibliography

[1] Tolkien’s maps. (2020, October 21). Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tolkien’s_maps

[2] The Lord of the Rings. (2020, November 05). Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Lord_of_the_Rings

[3] Maps Workshop – Developing the Fictional World through Mapping. (2019, April 16). Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://hollylisle.com/maps-workshop-developing-the-fictional-world-through-mapping/

[4] Grossman, L. (2019, October 02). Why We Feel So Compelled to Make Maps of Fictional Worlds. Retrieved November 12, 2020, from https://lithub.com/why-we-feel-so-compelled-to-make-maps-of-fictional-worlds/