Mrs Claire Baty, Head of French, looks at the idea of teachers being life-long learners, and the benefits this affords in our classrooms.

It’s widely accepted that learning something new can enhance your quality of life, give you confidence, have a positive impact on your mental health and above all be fun. “Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever” (Ghandi). Yet learning from scratch, purely for the cognitive challenge, is something that most of us rarely do.

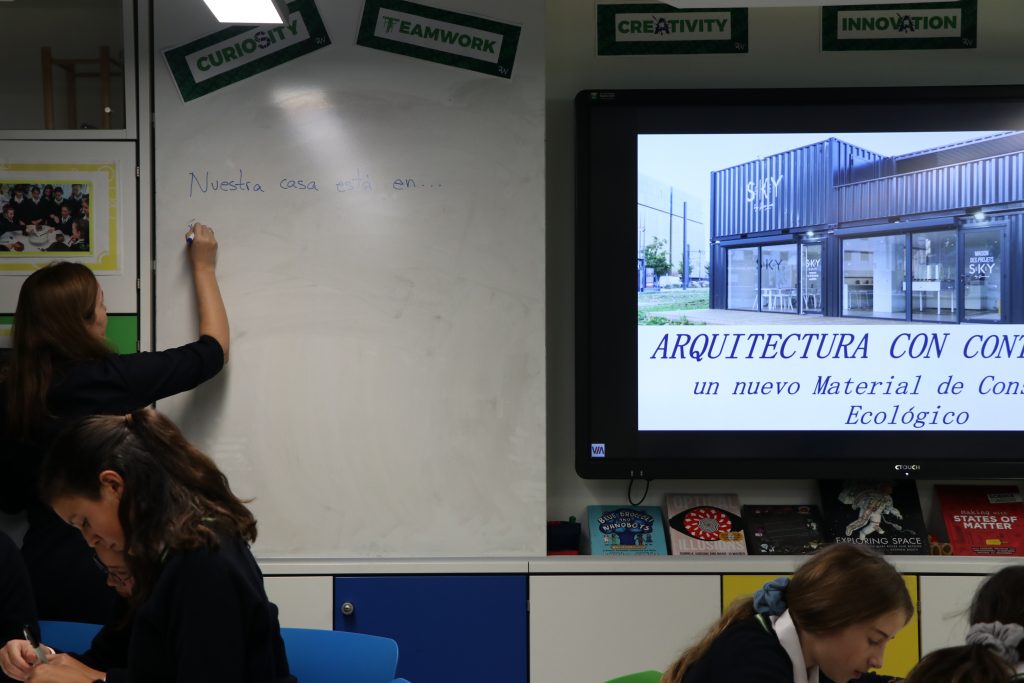

As a French teacher, my focus has always been on imparting knowledge; enthusing and, I hope, inspiring my students to learn this language that I have spent years studying. I encourage my students to be curious beyond the curriculum. I ask Key Stage 3 to look up extra words to extend their topic specific vocabulary beyond the confines of the textbook. I set Key Stage 4 longer, more authentic reading and listening texts to decipher, hoping to instil a desire to build upon their knowledge. I expect Key Stage 5 to indulge in research into cultural, literary and historical topics beyond the course. I hope that they do this with the same sense of pleasure that I feel when doing the exact same thing. Yet, I haven’t taken into consideration that for my students, especially those in Years 7-11, they are not yet fluent in this language. French is still new to them. When I read the news in French or look up a word from a novel I am reading, none of it is new, I am merely building on years of study, whereas my students are starting from scratch.

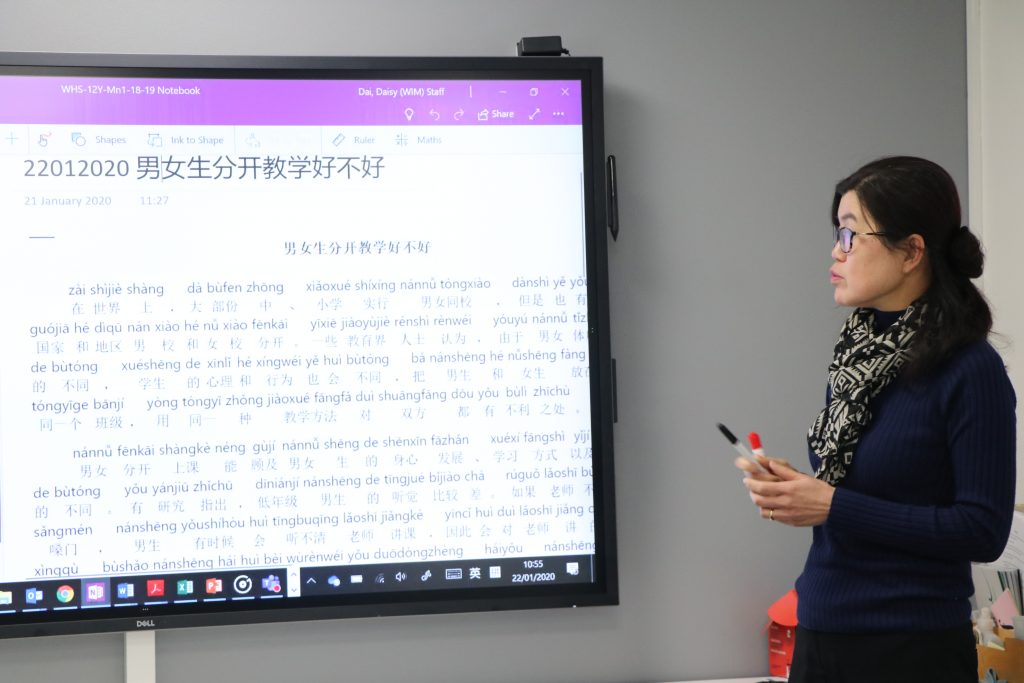

So to become the pupil again and experience language learning from the perspective of the student in the MFL classroom, was an opportunity that couldn’t be missed. Learning Mandarin alongside a class of Year 8 students is enlightening in so many ways. Not only have I learnt how to introduce myself and family in Mandarin, I have found myself reconsidering how we learn language and the effectiveness of our methods for the students that we teach.

The reality of learning a new language

Chinese is a fundamentally different language to the European languages that I am familiar with but, if I am totally honest, I expected to find it easy to make progress quickly, after all I am a linguist, a languages teacher and a motivated student with the advantage of knowing how to learn a language. In reality, it is proving less obvious than I had first thought!

My desire to always get it right has a direct impact on my confidence and self-consciousness when speaking in Mandarin. Even when I know the word I am profoundly aware of the lack of authenticity of my pronunciation. What is more, I was completely unprepared for how difficult it is to multi-task during a classroom based lesson. Copying vocabulary from the board, whilst listening to the sound of the word and trying to remember the meaning all at the same time as being prepared to answer a question from the teacher requires an agility of mind that is hard to achieve. But, perhaps most surprisingly for a linguist, is how hard I find it to recall new vocabulary from one lesson to the next without considerable pre-lesson preparation and sneaky glancing at notes! As a teacher, I often find myself saying to my French classes “but we saw this word last lesson in exercise X, page Y”. I now understand first-hand how difficult instant retrieval of vocabulary is, but also how important it is if you want to progress in a language.

If this is how I am feeling, when the language classroom is my ‘zone’, then how do my students feel? As teachers, do we ask too much of them each day or do they adapt to the demands placed upon them as learners and I am just out of practice?

How is second language taught?

Due to the closure of schools in March, my experience of learning Mandarin has moved from face-to-face classroom learning to independent textbook exercises, remote virtual learning and online platforms such as Duolingo, inadvertently placing me in a good position to consider this question.

In the MFL classroom we learn by rote, repetition, hearing others, practising, being creative with the language, revisiting previous knowledge. Independent access to a textbook is valuable to a point but then you need an expert to answer questions (and I have lots of questions!). Remote learning has become part of the ‘classroom’ experience and unexpectedly for me, the sense of anonymity created by initials in black squares during a TEAMS video conference has actually helped me to feel more confident when speaking in Mandarin and more inclined to take a risk. I wonder if my French students feel the same.

But what about all the online platforms available that claim they are the best way to learn a language? These applications offer a totally different approach to language learning. Often providing minimal explanation of key words or grammar, the focus is clearly on lots of practice, which means you get things wrong – all the time! To some extent this mimics how a child might learn a language; seeing and hearing words in context with lots of repetition. Whilst I must admit that these platforms are addictive because of their gaming style, I find myself wanting greater explanation. I want to read the notes, make my own notes, learn the information before attempting the exercise, whereas Duolingo seems determined to force me to have a go and risk getting it wrong.

What about the role of online translators? I have spent most of my working life warning students of the pitfalls of ‘Google Translate’. Every language teacher can give numerous examples of student’s work containing glaring and often comical errors, yet now that I am a beginner learner of Mandarin who is frustrated that the textbook glossary doesn’t contain the word I want to use, I find myself turning to Google Translate more and more frequently and with a surprising level of success. Perhaps the key here is that I am also a linguist and language teacher and hence know what pitfalls to look out for. But this does support what language teachers have been forced to accept; that A.I has transformed machine-based translation and Google Translate is no longer the enemy it once was. I agree whole heartedly with my colleague, Adèle Venter who, in her article Approaches to using online language tools and AI to aid language learning, says that students need to be taught how to use these tools rather than being told not to use them at all.

How does this affect my teaching?

What have I learnt from this whole experience, apart from being able to introduce myself and family in Chinese? Can learning a new language make me a better French teacher?

- Knowing how to learn helps you learn. I am at an advantage over my fellow Mandarin students, not because I am innately any better than them at Mandarin, but because I know how to take notes, revise vocabulary and practise the language independently. Activities aimed at improving pupil’s metacognitive skills must be a significant part of the classroom experience.

- It is also clear that retrieval practice needs to be a priority in every lesson. Ross Morrison-McGill (TeacherToolkit) makes an interesting link with the ‘knowledge’ test for London black cab drivers. According to his article Why do London cab drivers know so much? “spaced practice and interleaving” are the key to memory. I would also agree with Andy Tharby who comments in his article Memory Platforms that quizzing is a far more powerful tool to retrieval than re-reading notes or listening to teacher explanations. The latter create what he refers to as an ‘illusion of fluency’ – we think we know when in fact the knowledge doesn’t stick. Effective starter activities that encourage the transfer of knowledge from one lesson to another, one topic to another need to be incorporated into every lesson.

- Students need time in lessons to reflect, to consider what they are learning, to form and then ultimately ask questions and to consolidate their learning. Being overwhelmed, tired even anxious can all stem from a feeling of busyness that comes from having a distracted mind. We feel busy because we are in the habit of doing one thing while thinking about the next (mindful.org) Giving students time to process and complete the task I am asking of them during a lesson could lead to much deeper understanding and as a result, greater confidence.

I am not learning Mandarin because I have immediate plans to travel to China, nor do I need to use the language every day to communicate at home or at work (although I can see how it would be beneficial), I am learning purely for the sake of learning something new. It’s exciting to be able to do something that I couldn’t do 10 months ago. The change of perspective that has been afforded to me by becoming the pupil rather than the teacher is invaluable and I am excited to consider what I will change about my own classroom practice as a result.

Further reading and references

http://whs-blogs.co.uk/teaching/tag/mfl/ https://www.teachertoolkit.co.uk/ https://reflectingenglish.wordpress.com/2014/06/12/memory-platforms/ https://teacherhead.com/ https://www.mindful.org/a-mindfulness-practice-for-doing-one-thing-at-a-time/ https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/14/magazine/the-great-ai-awakening.html https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2017-05-01/language