Leah in Year 12 explores why the use of antimicrobials in commercial livestock agricultural medicine is such a contested issue.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has declared Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) as one of the Top 10 public health threats facing humanity[1]. While the use of antimicrobials has proved a huge boost to the livestock industry, in terms of faster growth in animals, the concern is that higher concentration of AMR in the food chain risks diminishing how effective antimicrobials will be in the human population.

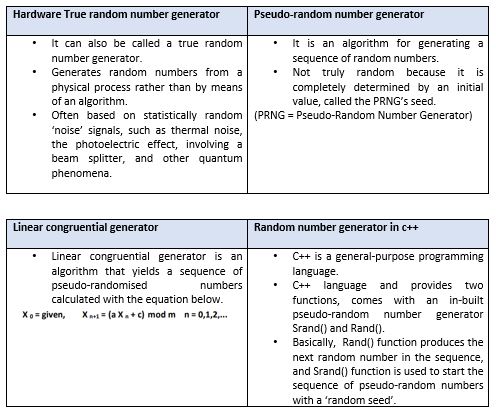

Antimicrobials are agents used to kill unwanted microorganisms by targeting the ones that may pose a threat to humans and animals. These include antibiotics and antibacterial medication for bacterial infections, antifungal medication for fungal infections and antiparasitic medication for parasites.

Resistance, or AMR, develops when antimicrobials are not used for their full course, so the weakest strains of bacteria are killed but the strongest ones survive. This means that the strongest strains then have the chance to adapt to the environment. Over time these variant alleles become more common in the population and the antimicrobials will become ineffective.

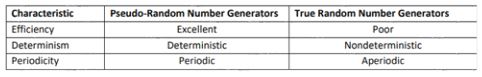

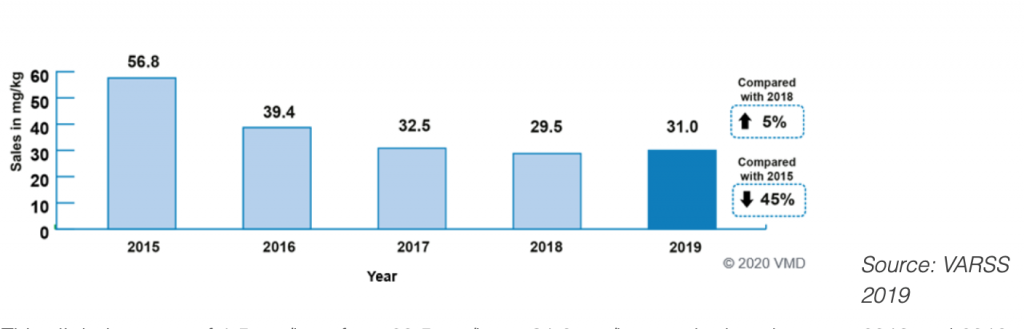

As Shown in the graph below[2]from 2015 to 2019, antimicrobial use in farming has actually decreased by 45% but since then has picked up again despite the issue becoming more widespread.

Antimicrobials are used often in the production of both meat and animal product farming such as dairy cows, with two main objectives: promoting growth and preventing disease.

The prevention of diseases in livestock are less of a contested issue as it is well understood that livestock share living spaces, food, and water. Generally, if one animal contracts a disease then the whole flock is at risk due to the proximity. Antimicrobials can help break this link.

However, the WHO has a strong viewpoint with antimicrobials as a growth agent.[3]As stated in their guidelines to reducing antimicrobial resistance, the organization believes that ‘antimicrobials should not be used in the absence of disease in animals.’[4]This happens by helping convert the feed that the farmers are giving to their livestock into muscle to cause more rapid growth. The quicker the animal meets slaughter weight the quicker they can send them off to an abattoir and get the profit. For example, a 44kg lamb produces 25kg of meat which is the heaviest a lamb can be so farmers want their lambs to reach 44kg so that they can get the most money from each lamb.

Over 400,000 people die each year from foodborne diseases each year. With the rise in antimicrobial resistance, these diseases will start to become untreatable. The most common pathogens transmitted through livestock and food to humans are non-typhoidal Salmonella (NTS), Campylobacter, and toxigenic Escherichia coli. Livestock contain all of these pathogens and so they can spread easily.

The WHO have been addressing AMR since 2001 and are advocating for it to become a more acknowledged issue. In some countries, the use of antimicrobials is already controlled. The US Food and Drugs Association (FDA) has been acting on this matter since 2014 due to the risk on human health.

Antimicrobial Resistance is a contested issue because, as much as AMR is a problem that has a variety of governing bodies backing it, there will always be the point that farmers rely on their livestock for their livelihoods meaning they are often driven by profit to ensure income. Antimicrobial Resistance has always been hard to collect evidence on, so this makes it harder to prove to these farmers that it is a growing issue.

References

[1] World Health Organization, WHO guidelines on use of medically important antimicrobials in food producing animals, 7 November 2017, https://www.who.int/foodsafety/areas_work/antimicrobial-resistance/cia_guidelines/en/

Accessed: 24th April 2021

[2] World Health Organization, Antimicrobial Resistance in in the food chain, November 2017, https://www.who.int/foodsafety/areas_work/antimicrobial-resistance/amrfoodchain/en/

Accessed: 24th April 2021

[3] World Health Organization, Ten threats to global health in 2019, https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019 Accessed: 24th April 2021

[4] Farm Antibiotics – Presenting the Facts, Progress across UK farming, https://www.farmantibiotics.org/progress-updates/progress-across-farming/

Accessed: 24th April 2021