Annabel (Year 13) looks at the impact of the British imperial history on the evolving relationship between the UK and the EU.

There is an argument to suggest that Euroscepticism, which has been a major part of our political narrative since the 1960s, has an imperialist undertone to it; as decolonisation came to a close, Euroscepticism rose up in its place. There is certainly room for this argument in today’s political climate as similarities can be drawn between the two ideas from an ideological point of view. Nevertheless, the ‘Leave’ campaign has a greater level of complexity to it than merely an overwhelming desire to return to days of imperialist superiority in the 19th century.

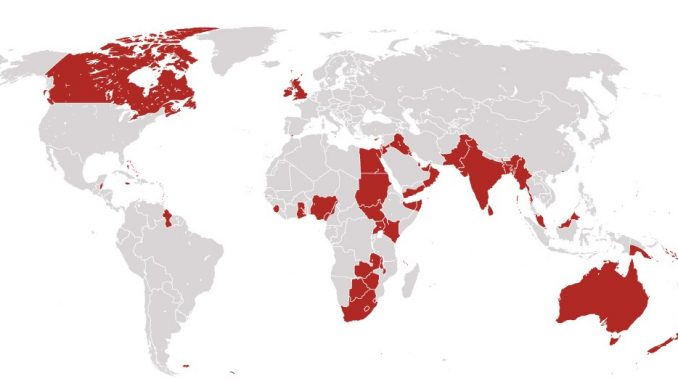

Firstly, British imperialism is an incredibly complex area of interest and reasoning for empire building changed dramatically from initial stages of adventure and exploration to its largest point in 1919, where the empire added 1.8 million square miles and 13 million subjects to its existing territory under the Treaty of Versailles.[1] The notion that British imperialism can be associated with a single motivation throughout the entire existence of the Empire is just too simplistic. How then, can we link imperialism to the motivations behind the ‘Leave’ campaign?

There are some commonalities throughout the British Empire’s existence that can be found and therefore associated (or not as the case may be) with the Eurosceptic narrative. Without question there are consistent undertones of British superiority throughout the time as metropole in one of the largest empires in history. Colonialism was associated initially with a desire to explore, and then claim, foreign lands. Humanitarian justification, through Social Darwinism and then increasingly through a motivation to decolonise, was an important aspect of imperialism. Above all, the competition between European neighbours, also imperialist powers at the time, was a key aspect of the British Empire and this is where the possible connection to Euroscepticism can be found.

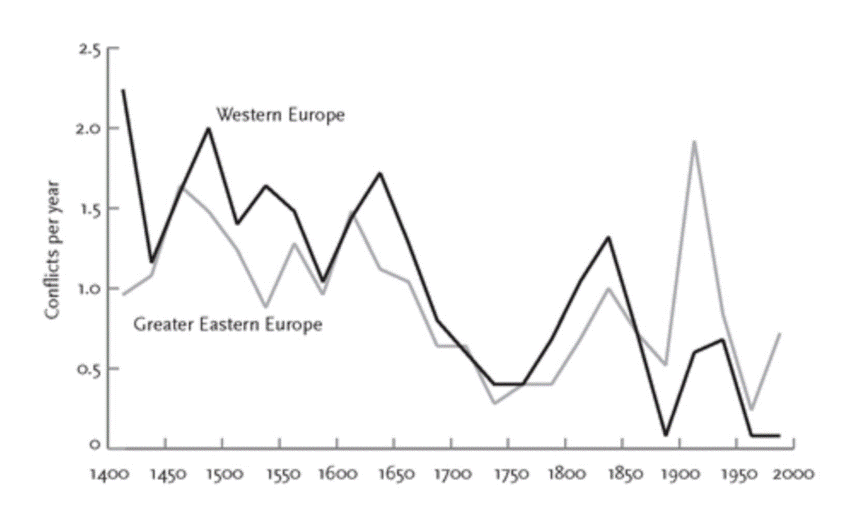

The British relationship with the EU has been complex from the outset and it was heavily debated whether membership should be granted to the UK throughout the 1960s. Britain’s desire to have a special relationship with the EEC due to the Commonwealth trade meant they were rejected by the EEC twice in the 1960s. French president at the time, Charles De Gaulle, determined that the British had a “deep-seated hostility” to any European project.[2] The hostility that De Gaulle mentions could be referencing the peripheral location of Britain and historical competitiveness with European nations that, as previously mentioned, were a key aspect of British, and indeed European, imperialism. There is arguably therefore a compatibility with a reluctance to be a part of the EU and the anti-European narrative of the British Empire.

The “deep-seated hostility” that De Gaulle mentioned could suggest that there is perhaps an unconscious bias of the British population against any collaborative effort amongst European countries. Bernard Porter argues in his work The Absent-Minded Imperialists that the British population was largely unaware of the impact of Empire on British society and held a more subconscious affiliation with its principles as opposed to a direct support of the motivations.[3] There are two possible consequences of his argument in relation to the EU, that the imperialist subconscious merely drifted away from the British cultural narrative, or that there remains a subconscious affiliation with the principles of British isolationism and European competition in the British population. It is undoubtedly difficult to pinpoint which one it is, but it is nonetheless interesting to consider how far the European relationship has been impacted by the British Empire.

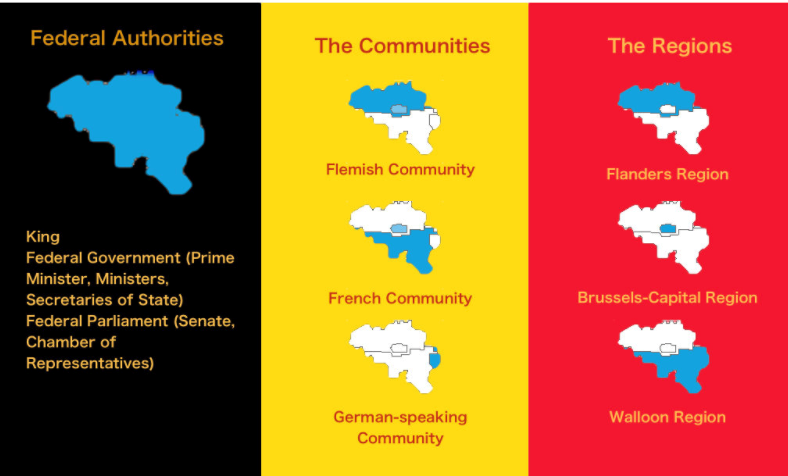

The British relationship with the EU has always been complex; Britain was not one of the 11 countries to join the Eurozone in 1999 and only voted to join the EEC in 1973, long after the ECSC was formed to prevent Franco-German conflict in 1951. The economic narrative of the EU was a key one in the ‘Leave’ campaign, as seen on the bus above, but arguably it was much more about cultural identity than the economic relationship between the UK and the EU. The tones of placing internal British priorities above those of regionalist policies in the EU could be seen to hold an aspect of British isolationism which was a key pillar of British imperialism in competition with other imperial European powers.

Ultimately, while there are certainly correlating elements between the narratives of imperialism and that of the ‘Leave’ campaign, it is incredibly difficult to pin down how far it is a conscious decision. There is, perhaps, an “absent-minded” aspect to the narrative that has retained some of the colonial narratives present in the days where the Empire placed Britain as a leading world power. Therefore, the desire to return to a powerful place, as was the case of Britain as an imperial power, might have provided a sub-conscious motivation for the desire to break away from historically rival European countries.

Bibliography:

Murphy, R. Jefferies, J. Gadsby, J. Global Politics for A Level Phillip Allen Publishing, 2017

Porter, B. The Absent-Minded Imperialists, Oxford University Press, 2006

Porter, B. The Lion’s Share: A History of British Imperialism 1850-2011, Routledge Publishing 2012

[1] Ferguson, Niall (2004b). Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02329-5.

[2] “1967: De Gaulle says ‘non’ to Britain – again”. BBC News. 27 November 1976. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

[3] The Absent-Minded Imperialists, Bernard Porter (2004)