This week’s WimLearn post is an extract from Hannah B’s EPQ about Belgium’s political system.

According to the Belgian constitution, citizens of this European country have the right to freedom of language, since its independence on 4th October 1830, and can, therefore, choose which language to conduct their daily lives in. Article 30 states that ‘only the law can rule on matters involving language, and only for acts of the public authorities, and in legal matters’ (Vermeire Elke, Documentation Centre on the Vlaamse Rand, 2010). The freedom of language for citizens also complicates political matters, in which national polling occurs because votes from both language-speaking sides must be collated and moderated for a fair system.

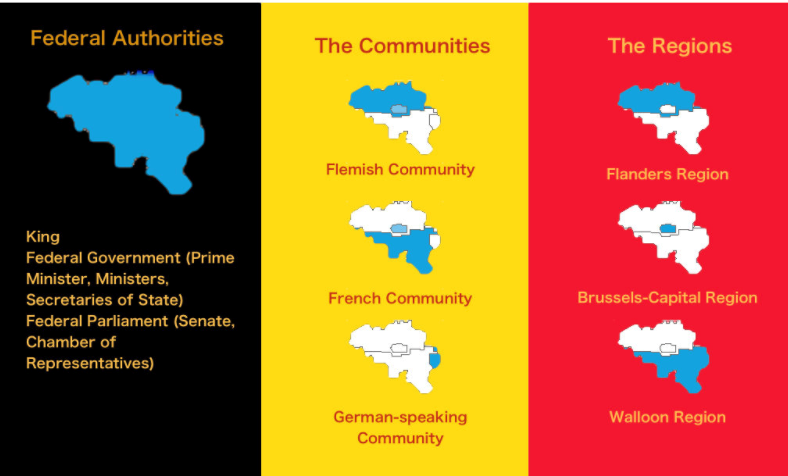

Additionally, article 4 states that “Belgium has four linguistic areas: The French-speaking area, the Dutch-speaking area, the bilingual area of Brussels Capital and the German-speaking area.” Around 55% of the Belgian population belong to the Flemish community, whilst 40% belong to the Walloon community, and just 1% to the German Community. However, 16% have Dutch as their second language, whilst 49% have French as their second language. Overall, this means that for the national government, ratios must be put in place to ensure that one linguistic group does not outweigh the other on the basis of their population.

Over the past 20 years, Belgium has not seen much political stability, largely due to their language divide. Belgium has a multi-party system, which means that political parties are often required to form coalition governments with each other. An issue that immediately arises when a coalition government must form is the parties’ cooperation.

In Belgium, this is made difficult by the languages that the two sides speak. Before political decisions are even made, the efficiency of the decision, that is who should form a coalition, is hindered. Whilst the regions are able to communicate with each other, both sides have preconceptions, and therefore hesitations to working together. These doubts are supported by the fact that, previously, Belgium has been without a government for 541 days, due to disagreements. The affect the language divide has on cooperation is seen here.

The fact that instant interpretation is often required would imply that the reason for Belgium’s political instability is due to their language divide, however this is not the case. There are 43 administrative arrondissements, which are an administrative level between the municipalities and the provinces. Each party must form a list of candidates for each of these arrondissements.

Arrondissements are split so that Flemish-speaking and French-speaking citizens will not fall under the same one. Many rules surrounding the use of language are put in place to minimise disagreement, and regional superiority. During political campaigns, there are restrictions on the use of billboards, and they only last for around one month. In national politics, politicians can choose to speak any of the three official languages, and the parliament will provide simultaneous interpretation. In this case, it would suggest that language is not the issue, but, instead, conflict of interest. All other official correspondence, such as tax returns, or passport requests, must be conducted in the official language of the region. At the age of 18, all citizens are automatically placed on the electoral roll, and are subject to compulsory voting.