In this week’s WimLearn, Lara K in Year 11 explores the ethical dilemma authorities face when regulating the dark web.

What is the Dark Web?

Often, the internet is thought of as one large, online platform. In actuality, the internet more closely resembles an iceberg with 3 layers: the surface web, the deep web, and finally, the dark web. The surface web is what you probably visit every day; accessible through a standard browser, this is where you find public pages like Wikipedia, YouTube and my Grandmother’s food blog. The next layer, the deep web, consists of web pages that are access-controlled (so not fully accessible to the public). For example, emails or bank records require a login, JSTOR has a paywall, even our school firefly website is on the deep web. The third layer, the dark web, exists on dark nets which requires special software to access. These dark websites take many forms: both small friend-to-friend peer-to-peer networks and popular, sprawling networks like Tor and I2P1. Many people, including academics and law enforcement agencies, have struggled to formulate an opinion on the dark web and- crucially- whether or not it should be allowed to continue.

Why Should We Shut Down the Dark Web?

Activity on the dark web is completely anonymous and very difficult to trace2. As a result of the anonymity, it’s becoming a cancerous hub for criminal activity that is near impossible for governments to regulate. In a 2015 study, researchers at King’s College London studied 2723 dark websites over 5 weeks- 57% of these sites hosted illegal content3. Recently, studies have placed this percentage even higher4. Prevalent crimes on the dark web include illicit (particularly child) pornography, publication of private/sensitive information, marketplaces which sell illegal materials: drugs, weapons, slaves, information (e.g. Netflix passwords or social security numbers), and services (e.g. hackers)5.[1]

This use of dark web markets means that terrorists, in particular, can undermine UN and governmental measures which aim to stop weaponry and other such resources from reaching them6. Furthermore, the use of encrypted communication (via the dark web) means that authorities are unable to intercept terrorist plans- potentially putting countless lives at risk. Evidence of this encryption was acquired in 2013 by the US National Security Agency which intercepted communications between the leaders of al-Qaeda6.

Why We Should Not Shut Down the Dark Web?

There are ethical concerns about whether removing the dark net would be justifiable. Contrarily to public perception, the dark web hosts numerous legal activities7– simply giving users access to private, surveillance-free communication without the anxiety of an accumulating digital footprint. For example, many dark web activities resemble the surface web (like Facebook8). As a result, some argue that attempts to terminate the dark web are authoritarian and impede freedom of speech.

Furthermore, dark websites can provide invaluable platforms for advocacy and whistleblowing- allowing people to overcome censorship or taboo. To illustrate, ProPublica is a Tor publication which gives readers access to journalistic content that their governments may have censored9. In fact, Human Rights Watch, in a statement to the UN Human Rights Council, declared:

“we urge all governments to promote the use of strong encryption technologies and to protect the right to seek, receive and impart information anonymously online.”10

So Should We Shut Down the Dark Web?

Despite ethical concerns, many countries have concluded that the criminality of the dark web outweighs any benefits of its existence. For instance, the UN- supposedly representative of the international body- has expressed concerns over the dark web11. Furthermore, the Centre for International Governance Innovation surveyed people across 24 countries: 71% of the respondents believed in dark net termination12.

Can we shut down the Dark Web?

In short, no; it is probably not feasible to shut down the whole dark web. Like the surface web, it consists of thousands of private websites- to shut each of these down, and ensure new websites don’t emerge, is simply impossible with current technology13. As with the internet itself, the dark web is not a centralised operation with one big red button to shut it all down.[2]

Instead, countries/organisations have attempted to shut down specific dark websites one-by-one- somewhat unsuccessfully. Even if a dark website is terminated, there is a sprawling network of pages from which another site will spring up in its place. For example, when the FBI shut down The Silk Road (a notorious dark net drug market) in 2013, dozens of similarly harmful replacement sites emerged4.

Other solutions?

Whilst shutting down the dark web is not feasible, there are several other approaches which may prove more fruitful. For example, many law enforcement agencies have tried rooting illegal activity out of the dark web. This has proved a challenging endeavour. Typically, authorities collect a range of evidence about cyber criminals (like IP) to catch and eventually prosecute them14. However, the dark web encryption means that tracing criminals is a technically complex, often futile process. Additionally, illegal dark web marketplace transactions can’t be tracked as the use of cryptocurrency (typically Bitcoin or Monero) renders both distributors and customers anonymous6.

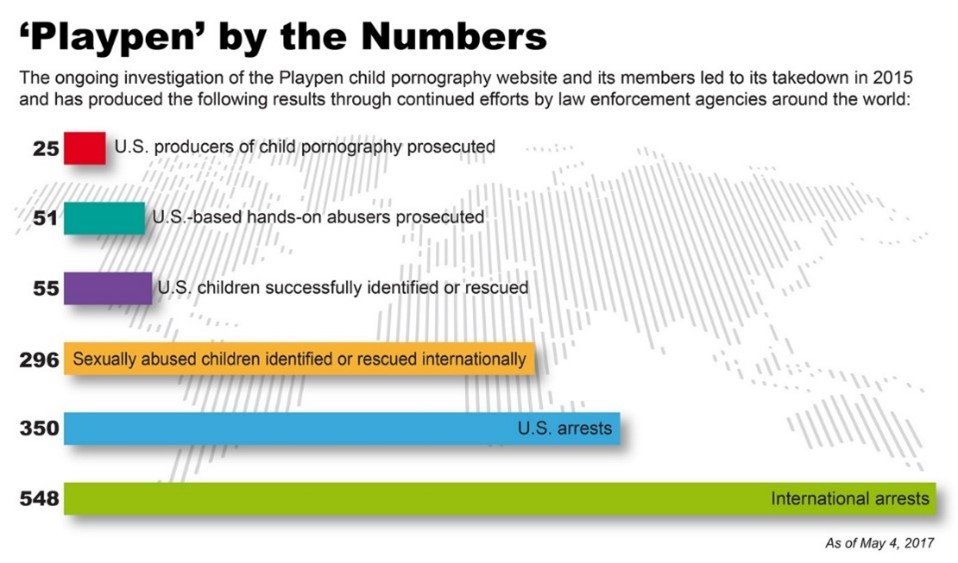

Another method is for law enforcement agencies to go undercover on the dark web. For example, in 2013 the FBI arrested Ross Ulbricht, the leader of the aforementioned Silk Road, after acting as an undercover agent on the site15. Similarly, the “honeypot trap” method has also proved successful, but deeply unethical1. In this method, law enforcement agents also go undercover on the dark web but partake in illicit activity with the aim of catching those who try to access the illicit content. Infamously, in 2014-2015 the FBI obtained a search warrant on “Playpen”- a dark website hosting child pornography. Instead of closing down the site, the FBI operated “Playpen” and received a further warrant to send malware to the devices of those who accessed the content. The malware searched their computers for child pornography and, using IP addresses, the FBI was able to locate criminals16. As a result, by May 2017, 548 related arrests were made17. However, by not terminating “Playpen”, the FBI was actively enabling the further spread of child pornography for nearly two weeks- allowing thousands of people access. Additionally, the malware used invaded the privacy of thousands16. It could be argued that the sweeping warrant issued to the FBI to use the malware breached the fourth amendment:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.18

Indeed, the malware “violated” thousands with surveillance- many of whom did not possess child pornography. In spite of this, the remarkable outcome of “Playpen” (shown below in the bar chart17) proves the effectiveness of undercover operations.[3]

Alternatively, countries have dealt with the dark web offline- drawing on the principle that the dark web is merely a platform to enable and display criminal activity; the actual crime happens in the real world with real people. Hence, organisations- like the UN- are working to improve regulatory measures which prevent crime before it reaches the dark web. To illustrate, the International Tracing Instrument (2005)19 legally requires small arms to be marked with identifying information (like serial number, country of manufacture and more) and record-keeping be kept on all weapons. With refinement and stricter adherence to the policy, this could enable law enforcement agencies to track down where dark web marketplace weapons are produced, supplied, and sold. Therefore, efforts to target relevant offline crime would be more targeted. The principle could be similarly applied to other dark web crimes.

Furthermore, increased social support could avert people from the dark web. This may include education about the risks and consequences of cybercrime. In the UK, cyber security/crime and ethics feature in computer science curricula20 and PSHE. Also, protecting and supporting those vulnerable to various aspects of dark web crime could curb illegal activity. For instance, the UK Prevent Strategy (2011) aims to prevent the radicalisation of people susceptible to terrorist recruitment using various methods21. From 2015-16, 7,631 people were referred to Prevent; 7,631 potential dark web terrorists had there been no intervention. Whilst Prevent was not ideal- facing allegations of institutionalised Islamophobia22– similar policies tackling each of the numerous dark web crimes could prove fruitful. For example, perhaps intervention could be provided to those vulnerable to trafficking, illicit sexual activity, drug abuse, illegal arms possession, and more.

Finally, many organisations have researched specific issues surrounding the dark web- aiming to increase the efficiency of tackling crime. For instance, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) collects data about dark web drug sales, publishing this in their annual world drug[4]report23 Developing knowledge and increasing transparency around the dark web can help guide international efforts against cybercrime and enlighten the public about the all-too-often misunderstood layer of the internet.

Perhaps, although there may never be a ‘lights out’ for the dark

web, there may be a ‘lights on’ for our understanding and our capability to

fight back.

References:

[1] 1D. Clayton. Addressing the Challenges of Enforcing the law on the Dark Web. Global Justice Blog. 11-11-2007. https://law.utah.edu/addressing-the-challenges-of-enforcing-the-law-on-the-dark-web/ (Accessed 2022-18-08)

2What is the Dark Web? Microsoft 365. 15-07-22. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365-life-hacks/privacy-and-safety/what-is-the-dark-web (Accessed 2022-18-08)

3D. Moore, T. Rid. Cryptopolitik and the Darknet. Survival, vol. 58, no. 1, 2016: pp. 7-384

4M. McGuire. Into Web of Profit Study Behind Dark Net Black Mirror. HP Threat Research Blog. 06-06-2019 https://threatresearch.ext.hp.com/study-explores-dark-net-enterprise-risk/ (Accessed 2022-03-09)

5E. Fisher. Dark Web Crimes. Find Law. 21-12-2021. https://www.findlaw.com/criminal/criminal-charges/dark-web-crimes.html (Accessed 2022-30-08)

6 G. Weimann. Going Darker? Center. 31-05-2018. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/going-darker-the-challenge-dark-net-terrorism (Accessed 2022-20-08)

7 M. Mirea, V. Wang, J. Jung. The not so dark side of the darknet: a qualitative study. Security Journal, vol. 32, 2019: pp. 102-118.

8 Wikipedia. 30-06-2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Facebook_onion_address (Accessed 2022-22-08)

9 C. Giwa. Why ProPublica Joined the Dark Web. Propublica. 19-01-2016. https://www.propublica.org/podcast/why-propublica-joined-the-dark-web (Accessed 2022-20-08)

10 Promote Strong Encryption and Anonymity in the Digital Age. Human Rights Watch. 17-06-2015. https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/06/17/promote-strong-encryption-and-anonymity-digital-age-0 (Accessed 2022-22-08)

11 Secretary-General Calls Cyberterrorism Using Social Media, Dark Web, ‘New Frontier’ in Security Council Ministerial Debate. UN Press. 25-09-2015. https://press.un.org/en/2019/sgsm19768.doc.htm (Accessed 2022-22-08)

12 S. Zohar. The “Dark Net” should be shut down: CIGI-Ipsos global survey: But what about its benefits? Centre for International Governance Innovation. 24-03-2016. https://www.cigionline.org/articles/dark-net-should-be-shut-down-cigi-ipsos-global-survey-what-about-its-benefits/ (Accessed 2022-22-08)

13 T. Leetim. The Dark Web: what it is, how it works, and why it’s not going away. Vox. 31-12-2014. https://www.vox.com/2014/12/31/7470965/dark-web-explained (Accessed 2022-02-09)

[3] 14 How Do Cybercriminals Get Caught? Norton. 18-01-2018. https://us.norton.com/internetsecurity-emerging-threats-how-do-cybercriminals-get-caught.html (Accessed 2022-25-08)

15 T. Hume. How FBI caught Ross Ulbricht, alleged creator of criminal marketplace Silk Road. CNN. 05-10-2013. https://edition.cnn.com/2013/10/04/world/americas/silk-road-ross-ulbricht/index.html (Accessed 2022-25-08)

16 M. Rumold. Playpen: The Story of the FBI’s Unprecedented and Illegal Hacking Operation. Electronic Frontier Foundation. 15-09-2016. https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2016/09/playpen-story-fbis-unprecedented-and-illegal-hacking-operation (Accessed 2022-25-08)

17 ‘Playpen’ Creator Sentenced to 30 Years. FBI. 05-05-2017. https://www.fbi.gov/news/stories/playpen-creator-sentenced-to-30-years (Accessed 2022-25-08)

18 J. Madison. US Constitution. Pennsylvania, 1787, amendment 4.

[4] 19 International Instrument to Enable States to Identify and Trace, in a Timely and Reliable Manner, Illicit Small Arms and Light Weapons, New York: United Nations, 2005

20 GCSE Computer Science (9-1)- J277. OCR https://www.ocr.org.uk/qualifications/gcse/computer-science-j277-from-2020/ (Accessed 2022-25-08)

21 HM Government. Prevent Strategy 2011. GOV.UK. 07-06-2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/prevent-strategy-2011 (Accessed 2022-25-08)

22 M. Versi. The latest Prevent figures show why the strategy needs an independent review. The Guardian. 10-11-2022 https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/nov/10/prevent-strategy-statistics-independent-review-home-office-muslims (Accessed 30-08-2022)

23 World Drug Report 2022. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. 2022. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2022.html (Accessed 2022-30-08)