Rebecca Owens, Head of Art at Wimbledon High School

Printmaking has always been one of the things I enjoyed the most when I studied at Camberwell School of Art. So, when I started at Wimbledon High School I decided to introduce as many of the techniques as possible. There is something magical about the processes as the results are always a bit unexpected. Rather like a good gardener will learn some strategies to help achieve the results she wants, and tame nature in the garden, she will inevitably have moments of surprise. The same is true of printmaking. Whilst you can learn the techniques and become more familiar with the results, there is often a WOW moment, and an unexpected outcome. As the German Expressionist Ernst Ludwig-Kirchner said:

‘The technical procedures doubtless release energies in the artist that remain unused in the much more lightweight processes of drawing or painting’ (remark on printmaking).

In this article I have outlined why I think printmaking is important, what the different types of printmaking are and how we use printmaking at Wimbledon High School.

Printmaking

Printmaking revolutionised how images were disseminated, with the first publication of books and the subsequent development of printed images in the mid fourteenth century enabling more people to own images, and for these images to be moved around. The letter press or moveable type, first mentioned in 1439, was designed by Johannes Gutenberg. The increased production of books over the next few decades meant that the price of paper dropped, and as a result, that artists had cheaper access to the media. Artists started to work in different ways, with woodcuts, wood engravings or engravings on metal often used to create the printed images found in books. In this respect, printmaking allowed the artist to be more egalitarian, and reach a much wider audience, as each print could be sold for less money than the original.

Why use printmaking in school

The process of printmaking allows students to work and think in a completely different way, as printed outcomes often have unexpected results. This characteristic of the process allows students to experiment liberally with the further development of their images. Indeed, the disconnection between a student’s expected outcome, and the physical reality of their print is part of the pleasure of printing, it liberates the artist and helps them to investigate unexpected and exciting ways of working. Once the screen or block has been created, the student can explore overprinting onto different surfaces, try differing colours schemes or experiment with making the two-dimensional print into a three-dimensional piece. Some students thrive and gain in confidence when they are constrained by some conventions to react against, or rules to break, as David Hockney states “limitations in art have never been a hindrance. I think they are a stimulant”.

There are many advantages to introducing the different skill set required for Printmaking, but one important reason to me is that it allows Art to be rewarding to a greater range of people. The boundaries in the technique encourage creativity.

“Learn the rules like a pro, so you can break them like an artist.”

― Pablo Picasso

Types of printmaking

Drypoint

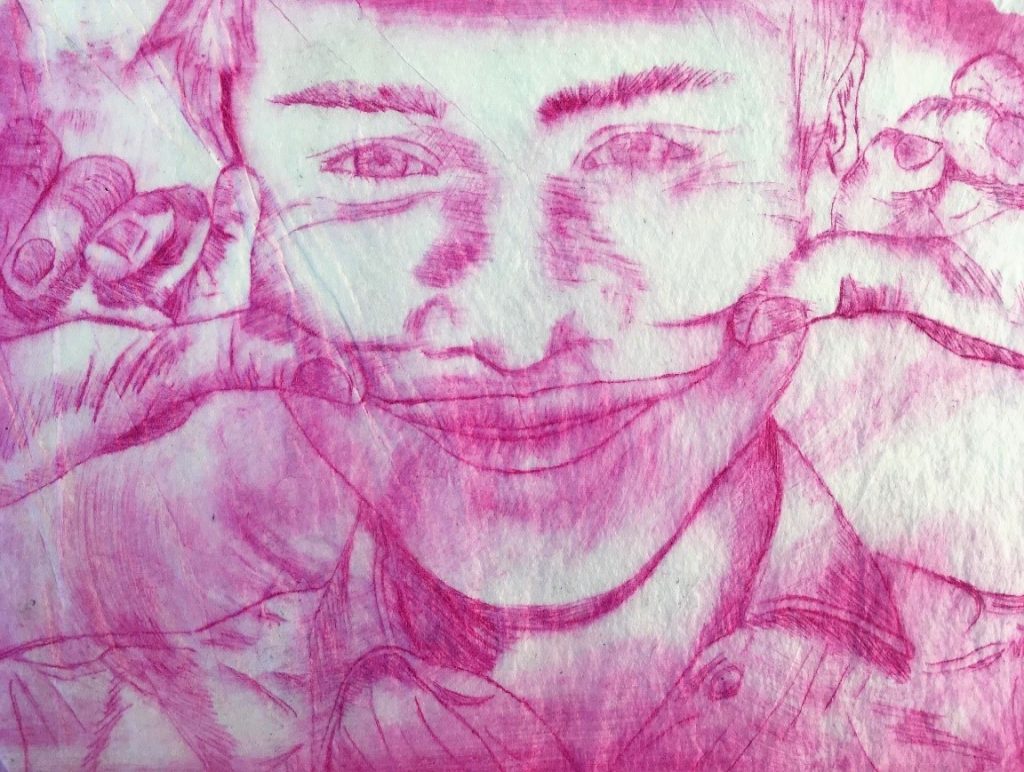

A drypoint needle is used to scratch into the plate, which may be metal or plastic. Ink is then rubbed into the plate. The paper is dampened before printing, so that as it passes between the two rollers, the ink is lifted out from the scratches.

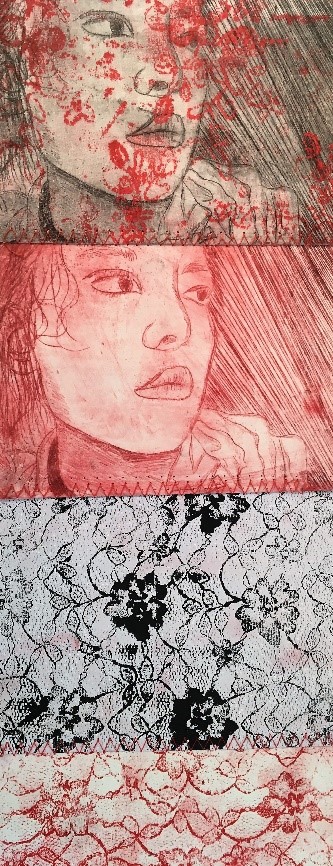

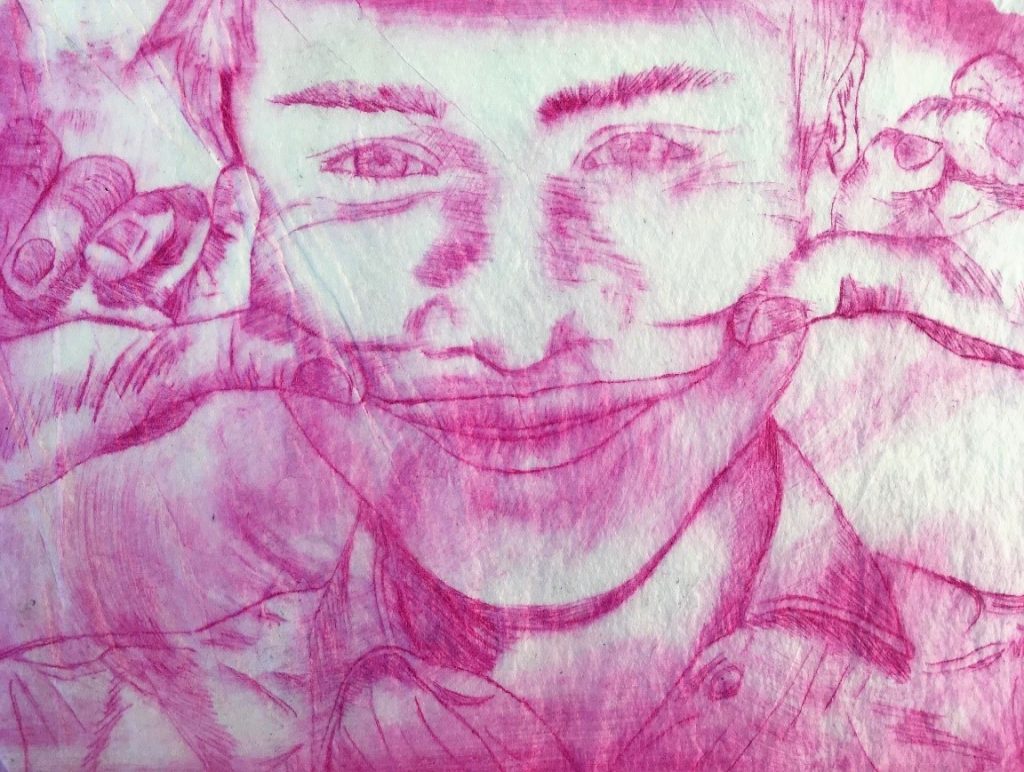

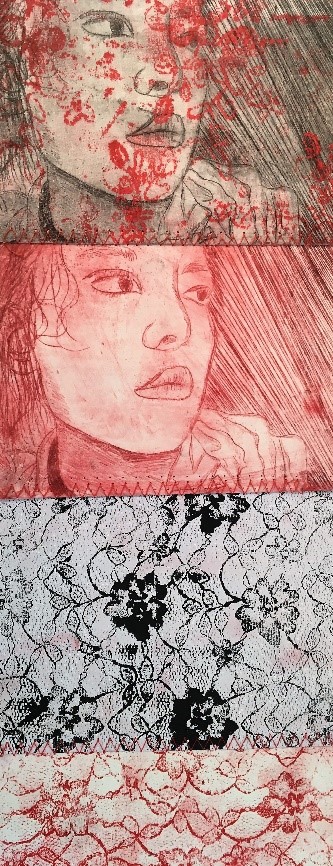

These prints are based on portrait images that the students took of themselves, their friends and family. The theme was reflections and distortions, where the students explored different reflective surfaces and other ways of distorting their images. The prints were created using an etching needle and a plastic plate. Professionals would use metal plates as they are more durable and so a bigger edition can be created.

Ruby (Year 10)

Ruby (Year 10)

Zara (Year 10)

Zara (Year 10)

Issie (Year 13)

Issie (Year 13)

Using a combination of etchings, rubbings of textured surfaces Issie created the laminates from which this installation was created. The images explored the contrasting shapes found in Kew gardens.

Etching

Plates are coated with different grounds, and the ground is then removed using the etching needles. The plates are placed in acid, where the acid etches into the metal, creating areas which will hold the ink during the printing process. This process is often combined with aquatint which achieves the graduated tones, as evident in the work of Norman Ackroyd. The artists’ beguiling, monochromatic works of the British Isles achieve a soft, seemingly watercolour-like effect through a combination of etching and aquatint processes. Explore his work here.

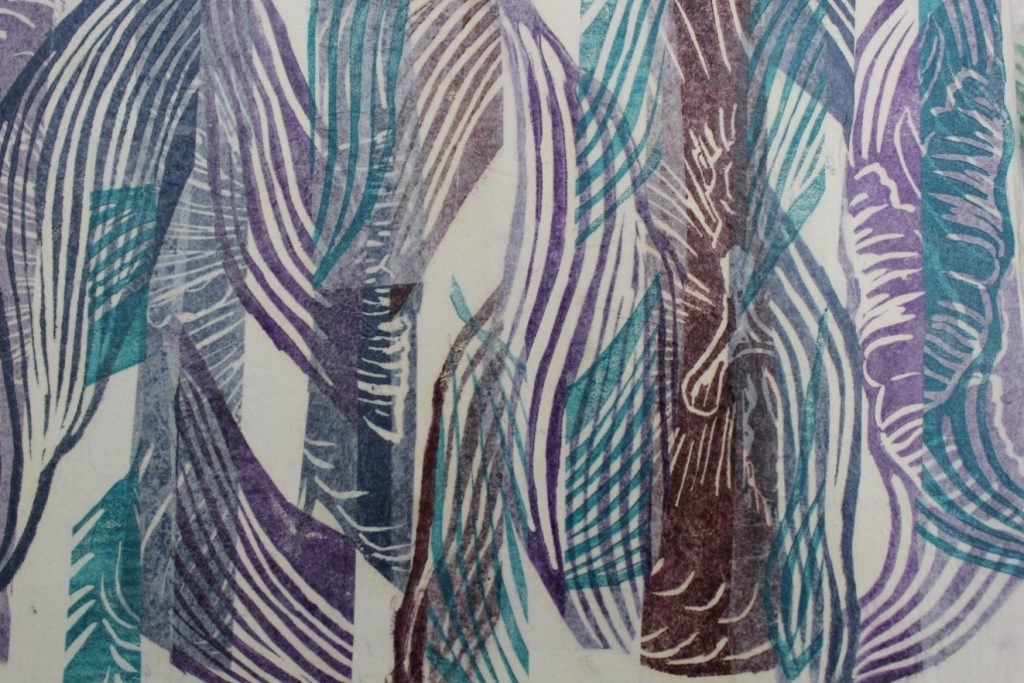

Woodcut printing

This technique uses blocks of wood where the grain is parallel to the printing surface. This allows for working on a bigger scale than wood engraving, and as the cuts follow the grain there can be some slipping as the design is cut. The grain of the wood is also evident in the print, with artists like Nash Gill using this characteristic of the process to add texture and interest to their compositions. Ink is applied using rollers and the lines cut remain the colour of the paper. The work of Kathe Kollwitz shows how the simplicity of a print can be used to create images which elicit an emotional response. She used her work to comment on society at the time focussing on poverty and loneliness. See her work here.

Wood engraving

This uses the end grain of wood, often box or lemon wood, as the grain is fine and consistent. As these woods are slow growing, the blocks available are smaller. The cutting process is very hard, requiring sharp tools, but there is less slipping as the tools are cutting across even grain. Ink is applied using rollers and the lines cut remain the colour of the paper. John Lawrence delicate and fine wood engravings have been used as illustrations in numerous fine art publications and books. See his work here.

Lino printing

Using linoleum to create the block. Lino is hessian backed and made from cork. It is easier to cut than wood prints, but has a similar bold effect. The lines cut do not hold the ink as the ink is applied using rollers to the surface of the block. Grayson Perry uses large scale lino prints to create his exciting images which present his critique and commentary on contemporary life. View his work here.

Year 7 Lino prints

Lino prints, akin to wood engravings, require the artist to work in reverse as the areas which are cut away do not hold the ink. Whereas lines are normally drawn in a dark colour on a light background, when working on a lino design it is necessary to reverse that process. For that reason, it is helpful when designing a lino print to make a plan using white chalk on black paper. As an introduction to lino printing Year 7 are shown how to work in this way. It has the additional benefit that white chalk is relatively tricky to create very fine marks with, so it encourages everyone to be bolder. Indeed this is also beneficial as it is difficult to cut out shapes which are too intricate.

Shanalia (Year 7)

Shanalia (Year 7)

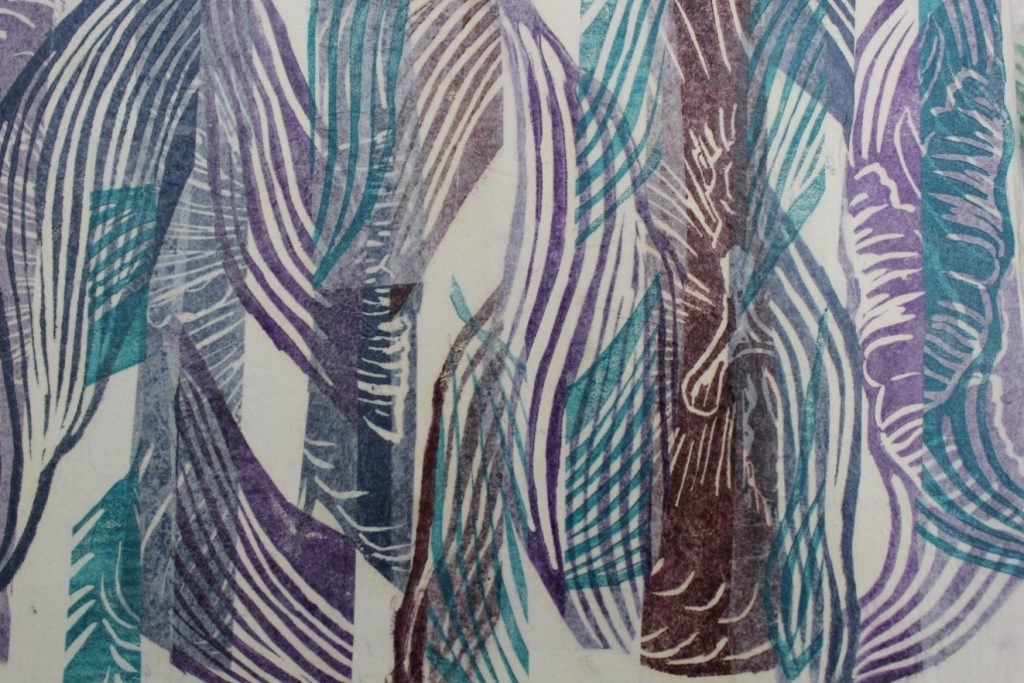

Tulip 1 by Rebecca Owens

I made this piece using Linocut prints on white tissue paper, collaged together. The rhythmic patterns in organic forms have always inspired my work. ‘Tulips 2’ aims to contrast the fluid shapes found in tulip flowers and leaves, with the geometric composition of the collage. I am fascinated by the delicacy and semi-transparent nature of the thin paper. The way the overlaying of the bold Lino prints creates unexpected focal points and a subtle range of colours, is also intriguing.

Monotype printing

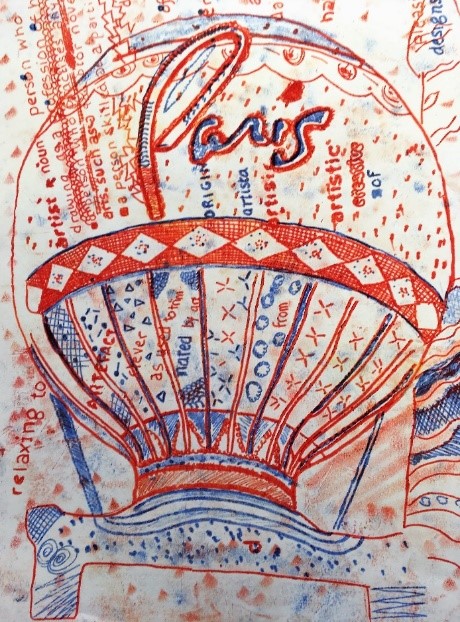

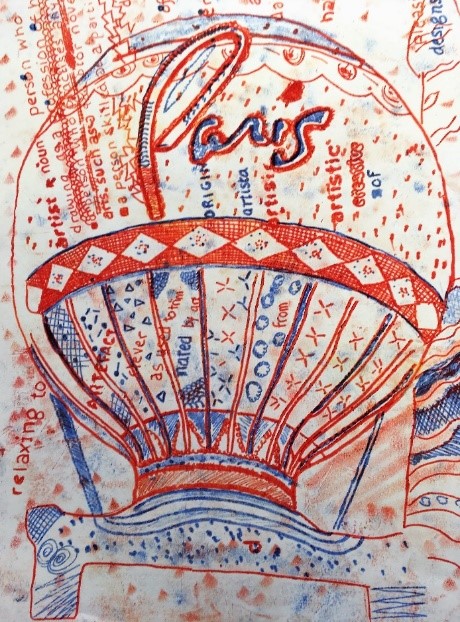

Kate (Year 9)

On the theme of Text in the Environment students in Year 9 took some amazing reference photographs from which to develop their ideas. They used these to create their monotype prints. As the name would suggest, these are one off prints, where the ink is rolled out or laid onto a board, paper or other flat surface and a second sheet of paper is laid onto the inked area. By drawing on the back of the paper the ink is transferred. It has the same wonderful sense of excitement and often gives an exciting moment in lessons, when students reveal their prints.

Eryngium – Monotype print by Rebecca Owens

Silk screen printing

Using a silk or synthetic mesh stretched over a screen. The ink is then pressed through the screen using squeegees. Stencils can by created for the screen using papercuts, by photographically transferring images onto the screen using light sensitive materials or by blocking the screen using stoppers. This media was used by artists such as Rauschenberg and Warhol in contrasting ways. Recently Ciara Phillips immersive installations created with prints engaged and intrigued the viewers, through her exploration of the process of printmaking. See her discuss her work here.

Year 11 and 13 mixed media work including prints.

These images demonstrate the exciting ways in which the students have experimented with these techniques.

Ava (created when she was in year 11)

Her screen prints on the theme of natural forms were folded to create this sculpture.

Lucy (Year 11)

In this piece she has combined pen drawing with screen printing.

Imogen (Year 13)

This large scale mixed- media piece contains etchings and screen prints which she used to create this sculptural piece.

Lithography

Using a stone or metal plate which has been sensitised to any greasy material, drawing is added using wax or chinagraph pencils. The plate is then brushed with liquid etch and coated with gum Arabic. The second stage of the process sees the black disappearing and leaving a waxy shadow. These will be the areas that hold the ink when printing. With lithography the plate has to be wet before ink is applied and kept damp.

Conclusion

Printmaking allows students flexibility and freedom to experiment. The contemporary artists included earlier in this article use printmaking to tackle important and universal themes through their printmaking. They are evidence that printmaking today is used by artists in increasingly diverse ways, to create artworks relevant to contemporary society.

Creativity allows students to develop different ways of thinking and as Art never has a right or wrong answer, there is a different thought process involved in solving a visual conundrum. Printmaking feeds into student’s visual vocabulary, allowing them the ability to express their ideas in a range of sophisticated ways, and helping them to express their thoughts and ideas..

“Art washes away from the soul the dust of everyday life.”

Pablo Picasso

Bibliography

A History of pictures by David Hockney and Martin Gayford – Thames and Hudson

Art The definitive visual guide by Andrew Graham-Dixon – Dorling Kindersley

The Encyclopaedia of Printmaking Techniques by Judy Martin – Quarto publishing

However, some people think that cities face a choice of building up or building out. Asserting that there’s nothing wrong with a tall building if it gives back more than it receives from the city. An example of a building succeeding to achieve this is the £435 million Shard, which massively attracted redevelopment to the London Bridge area. So, is this a way for London to meet rising demand to accommodate growing numbers of residents and workers?

However, some people think that cities face a choice of building up or building out. Asserting that there’s nothing wrong with a tall building if it gives back more than it receives from the city. An example of a building succeeding to achieve this is the £435 million Shard, which massively attracted redevelopment to the London Bridge area. So, is this a way for London to meet rising demand to accommodate growing numbers of residents and workers?

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.

Ruby (Year 10)

Ruby (Year 10) Zara (Year 10)

Zara (Year 10) Issie (Year 13)

Issie (Year 13)  Shanalia (Year 7)

Shanalia (Year 7)