Malin in Year 13 looks at the internationalisation of the English language, and the impacts this has had on the global community.

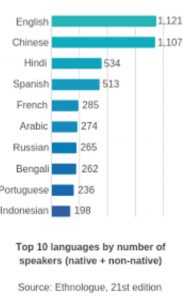

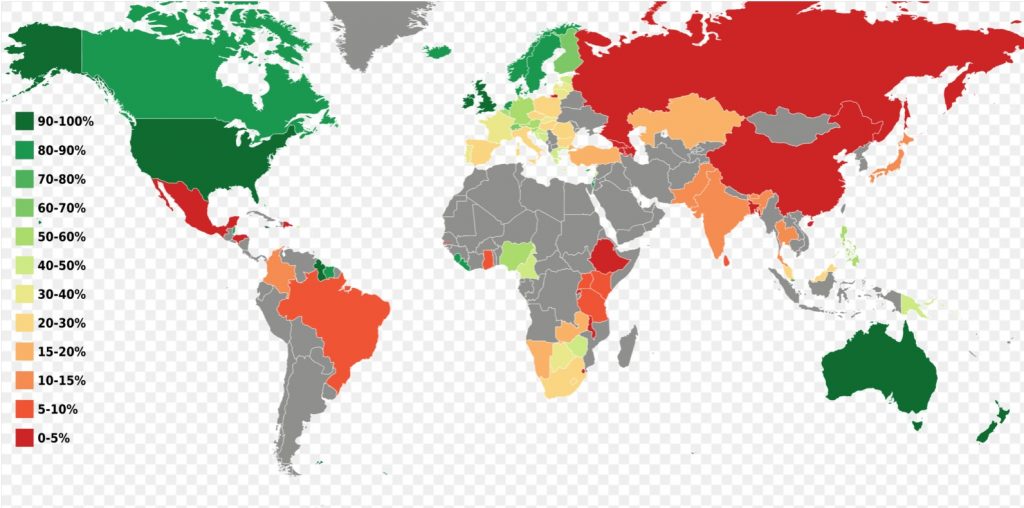

1.5 billion of the world’s population of 7.5 billion are able to speak English, albeit that only 380 million of these people speak it as their first language. The remaining 1.12 billion have learnt English as a second or third language, and this number is growing all the time given that English is the most commonly studied foreign language in the world. In my talk today, I will be exploring the extent to which the global expansion of the English language is a positive development for the world.

I will touch upon the pros and cons of the development of a dominant global language but also focus on some of the opportunities a greater ease of global communication can provide.

One of the most obvious pros of the increasing influence (and dominance) of English is that it provides a common language to make communication in a globalised age less difficult. This facilitates the transmission of world knowledge and increases understanding and interconnectedness, helping to draw unity from diversity. People from different countries and cultures around the world; Bermuda, Fiji, Ireland, Singapore, Guyana, America, can all come together and communicate with a shared language despite their apparent differences. A common language also extremely beneficial in the world of business as effective communication is key within many fields, such as international trade, banking and finance, as well as diplomacy, research and media. Through having people from different backgrounds work as a collective, numerous new opportunities for collaboration can arise.

Furthermore, in comparison to other widely spoken, international languages such as Spanish and Chinese, the English language is seen as a less redundant language due to its simple alphabet and the lack of a need to assign genders to nouns. This can make it easier for non-native speakers to learn, especially at a conversational level which in turn can explain the positive spread of the language due to its ‘face-surface simplicity’.

On the other hand, there is an acknowledged risk that the predominance of English as a common global language may result in the marginalisation of other less popular languages, whilst also encouraging a degree of cultural ignorance. With the success of English, particularly in international business, minority languages can be perceived as ‘unnecessary’ as they do not appear as useful in a number of scenarios – whether that is in an economic sense or in popular media. This creates a potentially hazardous situation where languages may die out, often resulting in the loss of valuable traditions, knowledge of certain cultural heritage, and life perspectives. For example, in Indonesia, where the national language is Bahasa Indonesia, due to the increasing global use of English, a mastery of Indonesian has become increasingly proportional to the social hierarchy, with the result that people who are fluent in English are considered to be of a higher class and more intellectually capable. As a result, Bahasa Indonesia has been demoted to a second-class status, where in some more extreme cases, Indonesians may take pride in speaking it poorly. There is a risk that this loss in popularity of minority languages could result in even greater ‘Westernisation’ of the world and a lack of interest in learning the culture of less dominant societies.

Furthermore, whilst communication barriers are being broken down between people from different countries, new generational barriers are developing between people living in the same country. Younger generations more comfortable in English will struggle to communicate with older generations who are less well equipped to learn English and newer ways of communicating (a multi-faceted problem not just of language), which again may inhibit the generational transmission of cultures and heritage.

Nevertheless, while it is likely that the use of less popular languages will decrease as the growth in the use of English spreads, it is always possible for people to learn English whilst still retaining their ability to speak their local language, hopefully ensuring that their heritage and culture is not completely lost.

Despite the global spread of English having potentially negative consequences for less popular languages and less dominant cultures, overall, it can be argued that the positives outweigh the negatives and the spread of English offers potentially significant opportunities through greater global communication, increased international understanding and economic well-being.

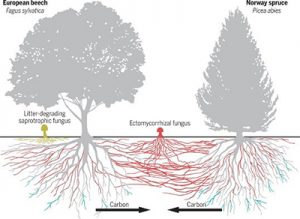

The driving researcher behind this work, Suzanne Simard, found that trees will help each other out when they’re in a bit of shade. She used carbon -14 trackers to monitor the movement of carbon from one tree to another. She found that the trees that grew in more light would send more carbon to the trees in shade, allowing them to photosynthesise more and so helping them provide food for themselves. At times when one tree had lost its leaves and so couldn’t photosynthesise as much, more carbon was sent to it from evergreen trees.

The driving researcher behind this work, Suzanne Simard, found that trees will help each other out when they’re in a bit of shade. She used carbon -14 trackers to monitor the movement of carbon from one tree to another. She found that the trees that grew in more light would send more carbon to the trees in shade, allowing them to photosynthesise more and so helping them provide food for themselves. At times when one tree had lost its leaves and so couldn’t photosynthesise as much, more carbon was sent to it from evergreen trees.