Gemma Norford, Head of Junior Music, looks at the impact instrumental music teaching can have on developing skills and a positive musical identity across WHS.

Introduction

As a PGCE student, you are taught that peer-to-peer teaching is an effective way of deepening the understanding of the learner taking the role of teacher, whilst also helping the pupil who is still grappling with the concept. This year, Junior and Senior pupils have come together in a musical programme called the ‘Rare Instrument Scheme’ where Senior pupils have been spending time teaching instrumental skills to Year 5 girls.

Why Music?

Music, on top of being a highly academic subject in its own right, is creative, practical and has the ability to shape lives inside and outside school. Amateur music, whether singing, playing or composing can also open up many opportunities for those of a post-school age. At primary level, music is integral to how the girls learn; how much quicker can you memorise a song than a piece of prose? The process of ‘trial and error’ seen as important skills in numeracy and literacy are echoed in the music room as girls persevere to rehearse and perfect their part for a concert performance.

Working in such ensembles promotes teamwork, a skill also paramount on the sports field. Reading and understanding musical notation is like deciphering complex equations in maths or algorithms in ICT. Norlund (2006), in a paper entitled Finding a systemized approach to Music Inclusion, states that when it comes to ‘standard’ classroom inclusion methods, ‘music classes are inherently different in that few general education classrooms demand as much group cooperation and interaction, and they require rapid acquisition of many academic skills…[while] performing complex psychomotor tasks.[1]

Why a Rare Instrument Scheme?

The Rare Instrument Scheme was designed with the aim of introducing ‘rarer’ orchestral instruments to Junior pupils through a year of small group tuition. As these instruments are often harder to come by both in schools and within the wider musical community, ensemble opportunities earlier on in their musical career would increase. This would, by default, promote a more positive musical identity within a larger amount of girls and encourage them to continue their instrumental studies.

Musical Identity

Music psychologists such as Meill (2002) suggest that a child’s development of musical identity is a mixture of ‘biological predispositions towards musicality’, and significant social influences encountered in daily life. These influences form an ‘integral part of those identities rather than merely providing the framework or context within which they develop’[2].

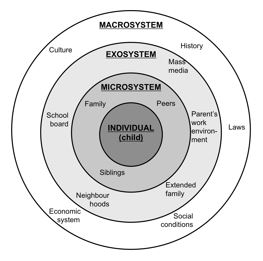

The idea of musical identity, though still a comparatively modern concept and one too big to unravel in this article, is a thoroughly fascinating arm of psychology. The term identity, in the psychological sense, is tightly caught up within the idea of the ‘self’ as well as within a wider ‘cultural’ sphere, which can be commonly linked to inclusion. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological model (figure 1) supports Meill’s idea that teachers have a strong part to play in the development of a child’s musical identity. What is even more important is that Bronfenbrenner (1979) and theorists such as McLaren & Hawe, 2005; Richard et al., 2011, ‘describe these levels as interactional rather than hierarchical’.[3] Thus the impact the senior girls as ‘teachers’, have within the Rare Instrument Scheme is playing a pivotal part on the development of the junior girls’ musical identity.

[1] Gfeller, 1989 in M. Norland, ‘Finding a systemized approach to Music Inclusion’, General Music Today, 19(3), p14

[2] D. Meill in (ed.), R. A. R. MacDonald, D. J. Hargreaves, and D. Meil Musical Identities, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002 p7.

[3] Crooke, A H D, (2015) https://voices.no/index.php/voices/article/view/829/685 (accessed January 2017).

Musical identity at a crucial age

Lamont (2002) argues that, when discussing identity, ‘two important topics need to be considered…first, self-understanding, or how we understand and define ourselves as individuals; and secondly, self-other understanding, or how we understand, define and relate to others.’[1] Lamont highlights this ability to differentiate between the two occurs around the age of 7; it is only once this idea of ‘differentiated identity’[2] is reached, that a child can truly begin to develop their own musical identity. The idea of children progressing through different psychological ‘levels’ is also one referred to in the work of Piaget.[3]

More worryingly, a study undertaken by O’Neill, which included 172 children (ages 6-11 years), concluded that children were much more likely “…to endorse an incremental (flexible) view about athletic ability than about musical and intellectual abilities. Also, children who had never played an instrument before were far more likely to endorse an entity (fixed) view of musical ability than children who were already involved in, or about to begin, instrumental training. These self–theories have important implications for the ways in which individuals make self-evaluations about their own and others’ ability.”[4]

Although O’Neill’s research fails to differentiate specific opinions of the participants based on their exact age, this is a salient point as children are applying their self-other understanding quickly which puts some at risk of identifying as a ‘non-musician’ as they are not a ‘trained musician’[5]. This can also link to concerns around the question of inclusion and social mobility.

WHS’s Rare Instrument Scheme, however, is happening towards the beginning of this crucial time. By ensuring each girl gets the opportunity to play an instrument, any pre-constructed ‘fixed’ views linking musical identity to instrumental playing can begin to be broken down as this is something entirely inclusive. Indeed, if the child walks away from this scheme identifying as either a ‘playing musician’ or ‘trained musician’ over a ‘non-musician’, the scheme has been a success.

Some of the most accomplished musicians have had successful careers as ‘playing musicians’ who are not necessarily classically trained. The positive outcomes of the Rare Instrument Scheme are already evident from both Juniors and Seniors. The Senior pupils have built incredible relationships with the Junior girls who show great respect to them. The comment from a number of Junior pupils that they would have much rather had another viola lesson than go to the House Christmas party really said it all: this scheme is promoting great enjoyment as well as musical skills and positive musical identities.

Learning for all

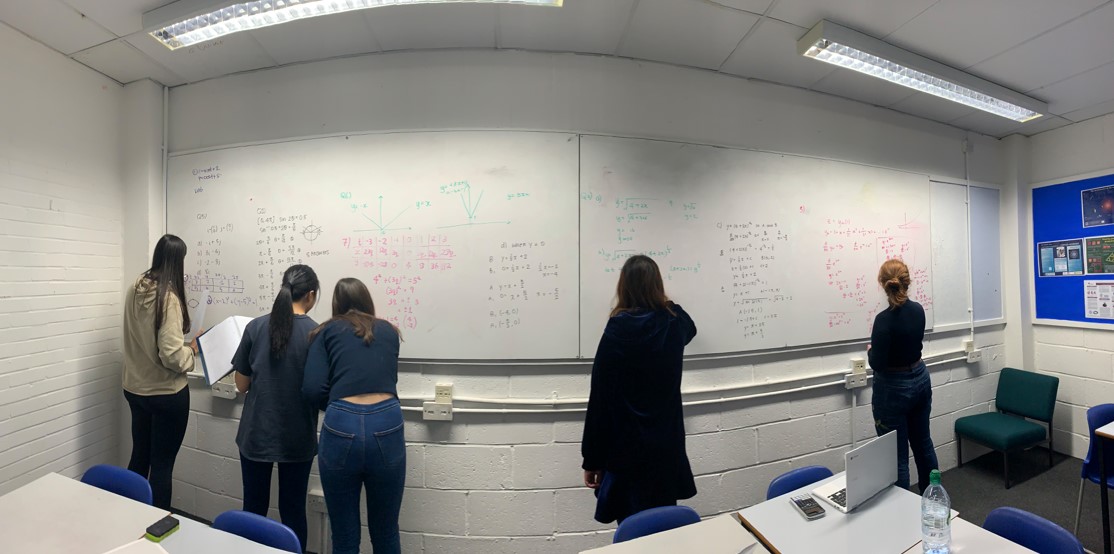

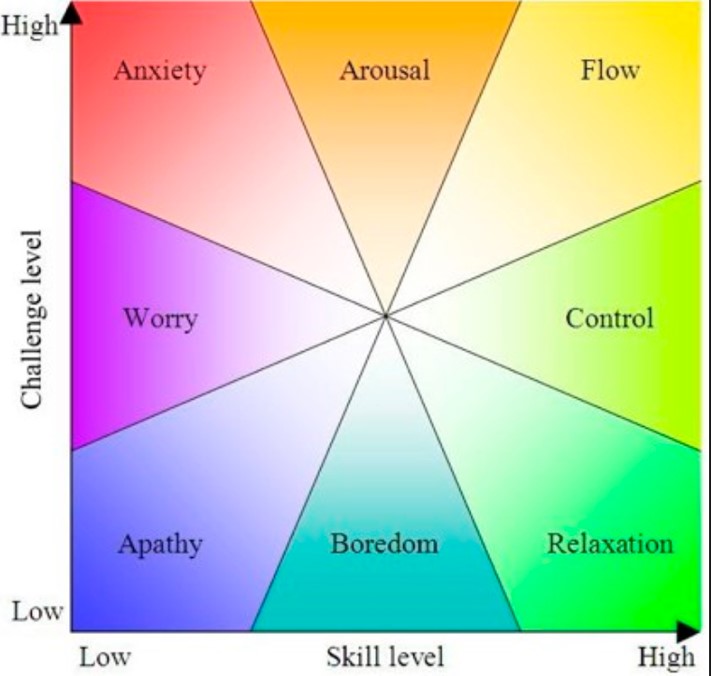

The involvement of the five Senior pupils has been a joy to see this year. They have been spending their two hours of enrichment a week with the Year 5 pupils and have put in an inordinate amount of effort to be the best they can be. The progress that I have seen in both groups over the course of just over a term has been truly enriching. One Senior pupil commented that it is great being able to learn to teach as she is thinking of going into it professionally following her degree. The skills the Senior pupils are developing are numerous. They are learning how to plan for a lesson; how to adapt their plan as they go depending on their audience; how to break down musical concepts in a way younger children can access thus deepening their own knowledge; how to both extend and support those who need it and how to deal with groups of young children. In a sense, they have also rediscovered their own passion for music through the excitement and enthusiasm of the Juniors as the younger girls explore their instruments for the first time. The Seniors are learning all this in a completely safe environment that allows them to take risks as they experiment with different approaches and tasks in order to develop these skills – something not always available to PGCE students at 21 or above.

The Seniors take a practical approach to leading viola lessons. They allow the younger girls lots of time to practise small chunks of music thus promoting the idea of being a ‘playing musician’ and allow the girls ownership of their learning. Junior pupils have relished this ‘freedom’ and are always keen to try the next bit! Having up to five Seniors and myself in the room may be a squeeze at times, but it ensures each Junior girl receives a large amount of one-to-one support. In about five weeks the Juniors were all able to play Twinkle Twinkle on their viola, including harmony lines for some as an extension, and the finger pattern for three major scales. Having been introduced to teaching through large group instrumental teaching (then call the ‘Wider Opportunities’ scheme) myself, I have been very impressed with the progress the Junior pupils have made. Yes, our classes are, purposefully, 12 and under rather than 30, but Twinkle Twinkle was not attempted for at least two terms in the scheme I was ‘brought up’ in – this is credit to both Junior and Senior girls at WHS. Response from the Senior girls’ parents has also been very supportive. One parent mentioned that her daughter came back into school one day following an appointment especially to do the Rare Instrument Scheme as she didn’t want to miss it.

Final thoughts

The positive effects of this enrichment scheme are numerous. For Seniors, it is the opportunity to teach, deepen their own knowledge, build skills sought after by universities and refine and affirm their own musical identity. For Juniors it is helping them construct a more positive musical identity, having contact with older girls who hold a positive musical identity and being given access to an instrument, which may open the door to musical opportunities sooner than they think as a ‘playing musician’ or ‘trained musician’. Although the academic research behind such concepts as musical identity and teaching as a way of deepening one’s own learning is necessary to support a scheme like this, I would argue they are not, in themselves, sufficient to justify the benefits of this project. It is the comments, enthusiasm and the music from the girls, both Senior and Junior, which really yield the true power of this enrichment scheme.

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

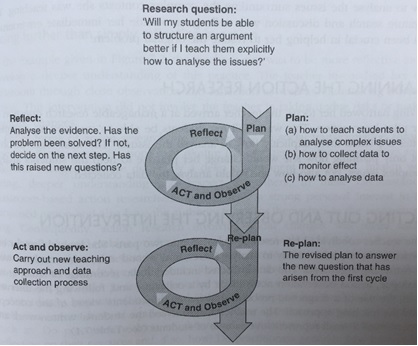

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing. Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.

Teacher support during the lesson is formative and needs to turn a spotlight on successes, hitches, failures, resilience, problems and solutions. For example, the teacher might interrupt learning briefly to point out that some groups have had a problem but after some frustrations, one pupil’s bright idea changed their fortunes. The other groups are then encouraged to refocus and to try to also find a good way to solve a specific problem. There might be a reason why problems are happening. Some groups may need some scaffolding or targeted questioning to help them think their way through hitches.