Ms Lucinda Gilchrist, Head of English, considers the roles of writing and grammar across subjects.

For English teachers, addressing writing and grammar skills is our bread-and-butter. However, in 2012, Ofqual introduced directive that in History, Geography, and Religious Studies, 5% of marks must be allocated to what is traditionally known as ‘SPaG’, or spelling, punctuation and grammar. Meanwhile, all other subjects with a significant written component must ‘make similar requirements for appropriate grammar, spelling, punctuation and legibility’ (Ofqual, 2015: 4). And of course, even more importantly, we need to ensure that pupils understand what is going on around them and communicate clearly in the world outside school. Not only that, but literacy is a form of social and academic empowerment, ensuring that all of us are able to access and interact with texts in a range of academic fields and social situations.

In a recent survey of WHS teachers, 68% of respondents agreed that ‘writing is important in my subject’, and 64% agreed that ‘the crafting of writing has a place in my subject area’. But what is really interesting about this is that, despite clear agreement that writing and grammar skills are important, there isn’t really much consensus of what grammar actually is, how much time and energy teachers across subjects should dedicate to it, and why it is important. If writing and grammar are so universally agreed to be important, it’s even more crucial to unpack what we mean by these terms, and how therefore we should approach them in our teaching.

Defining grammar

So, what do we even mean by grammar? Even this is hotly contested. In the survey, what was particularly interesting was that there wasn’t much agreement of what grammar is, and therefore what role it should play, even within subjects, with even Maths teachers having different views on the importance of writing in their subject. Much of the literature suggests that this is also down to our own perceptions of our competence in writing and grammar (for more on this, see Wilson and Myhill, 2012). Of course, on the broadest level, there is the macro-level view of grammar as the ‘structure’ of a language, an idea which came up in 32% of responses to the survey. However, when it comes to teaching grammar for writing in academic contexts, there are essentially two main approaches to grammar, although, as there is with any debate in education, polarisation of these views is unhelpful.

Most common is the correction/accuracy model, which perceives language as a set of pre-determined rules of spelling, punctuation and grammar (or ‘SPaG’) to which writers must adhere for the sake of clarity and erudition. In a recent survey of WHS teachers, words and phrases associated with this model came up frequently, with 64% of responses referring to ‘accurate’, ‘correct’, ‘proper’ or ‘clear’ English as the aim of teaching grammar. Traditionally, this approach would result in grammar taught primarily through decontextualized practice questions, unflatteringly called the ‘drill and kill’ approach by Laura Micciche of the University of Cincinnati (Micciche, 2004). This has also led this approach to be characterised as a ‘traditional’ (Hudson, 2004) approach to teaching grammar, and although we have moved beyond yawn-inducing practice exercises in teaching English grammar, it is worth interrogating what this model assumes about language and how this informs the way we teach it.

The main assumption is that there is a single version of English which is universally agreed upon to be the ‘correct’ version of English. When we mark pupils’ work, of course we have to contend with the bug-bears of misused apostrophes, comma splices and ‘would ofs’ instead of ‘would haves’, but this could end up being a very reductive view of what language actually is. Linguistically speaking, what we are judging pupils’ work against is Standard English, which is essentially just another dialect of English, in the same way Scouse, Mancunian and Estuary English are all dialects – dialect here referring to the grammar and vocabulary as opposed to the pronunciation. However, unlike other dialects, Standard English has less to do with geography and more to do with class and social groupings; it is a prestigious form of language descended from 1950s BBC English, into which we have to induct pupils so that the writing they produce means they can be taken seriously as scholars.

However, Standard English is more complex than that. Compare the sentences below:

- Father was exceedingly fatigued after his lengthy peregrination.

- Dad was exhausted after his long journey.

- Dad was well tired after his journey.

- Father were very tired after his lengthy journey

- My old man was knackered after his trip.

Evidently, the first is not Standard English; the register is absurd for most everyday language contexts, and many of us I’m sure would caution pupils who were writing like this against ‘over-writing’. And it would certainly not be fair, or even politically correct, to tell a Cornish or Welsh dialect speaker that the way they were speaking was ‘wrong’. The only one of those examples which most would agree is Standard English is the second, but it’s hardly eloquent prose.

More than just correcting errors

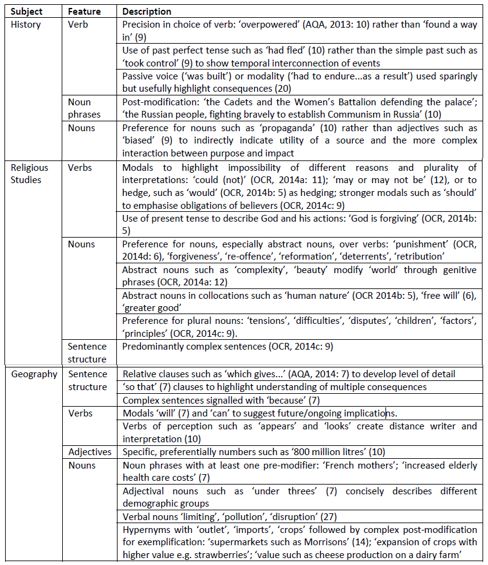

An added layer of complexity here in that we are asking pupils to actually develop a good understanding of different types of English within the dialect of Standard English; using phrases such as ‘CO2’ and ‘ox-bow lakes’ would sound very weird in a Philosophy essay. And this isn’t just at the level of vocabulary: in different subjects, there are different syntactical structures which are held to be more prestigious than others. For my MA research, I undertook some analysis of the indicative content in GCSE mark schemes in History, Geography and Religious Studies. You can see some of the key features in the table below, where you’ll notice that there are quite clear differences in the expectations of language usage for each subject area.

Evidently, it’s not as simple as being right and wrong when it comes to grammar – but that doesn’t mean that the other main model of grammar teaching is a case of throwing the rule-book out of the window in abandon, even if what is traditionally known as ‘SPaG’ isn’t explicitly part of the mark scheme in the English Literature iGCSE; the only reference to the quality of writing in the mark scheme is for AO4, worth 25%, which refers to a need to ‘communicate a sensitive and informed response’.

Before we throw our hands up in horror, let’s unpack the genre-based model of grammar first. This model essentially posits that different academic subjects have their own very specific rules and conventions, which pupils will need to confidently use to write convincingly within their subject areas. Thankfully, 92% of responses to the survey disagreed that grammar should only be taught in English; with the genre-based model, part of the requirement of all teachers, regardless of subject area, is to teach pupils how to successfully craft their language for the academic genre they are using, and many subjects have several academic genres: consider the difference between a case study and a discursive essay, for instance. We can see this from our everyday language too: examples of non-Standard English which would be acceptable in a text message or shopping list would not be acceptable in an email or formal school communication, but that doesn’t make them ‘wrong’ in the appropriate context. In this approach to teaching grammar and writing, teaching grammar is a case of making explicit the different ways of writing in different subjects and the appropriate generic conventions.

What next?

So, how do we do this? Unfortunately, there isn’t an easy answer here, and with increasingly challenging examination specifications and curricula, nearly 50% of us cited ‘curriculum pressure’ and ‘time’ being the main hindrances preventing us from tackling grammar as much as we would like. Other major hindrances are our own confidence and knowledge of grammar; given that in the 1980s grammar teaching had all but disappeared from the curriculum, many teachers were either not explicitly taught any grammar, or taught by teachers who themselves were not explicitly taught any grammar, hardly an auspicious start for teaching an area which we so overwhelmingly agree to be important.

However, I think there is also scope to be excited about this challenge, to help pupils see their writing within subjects less as ‘Is this right?’, and more as ‘How much do I sound like a trustworthy and intelligent scholar within this academic genre?’ In English, we regularly consider this through the lens of literature: how do modal verbs e.g. ‘shall’ convey the forcefulness of Old Major’s political speeches in Animal Farm, or how do reflexive verbs highlight Ralph’s self-control in Lord of the Flies? It’s a process which can work just as well applied to subject-specific writing, and to do that, we need to open up the dialogue about grammar, seeing it not as a closed and monolithic body of knowledge possessed by a prestigious few, but as something that within our own subject areas, we absolutely are experts in.

References

- AQA (2013) GCSE History B 91452 Twentieth Century Depth Studies Specimen Mark Scheme for June 2015 examinations. 6. [online] Available http://filestore.aqa.org.uk/subjects/AQA‐91452‐WSMS‐JUN15.PDF [Accessed 16/05/19].

- AQA (2014) GCSE Geography Paper 2 90302H Mark scheme. [online] Available at http://filestore.aqa.org.uk/subjects/AQA‐90302H‐W‐MS‐JUN14.PDF [accessed 16/05/19].

- Hudson, R. (2004). Why education needs linguistics. Journal of Linguistics. 40(1): 105‐30.

- Micchiche, L. (2004) Making a case for rhetorical grammar. College Composition and Communication. 55(4): 716‐737. http://www.csun.edu/~bashforth/305_PDF/305_PDF_Grammar/MakingACaseForRhetoricalGrammar_Micciche.pdf

- OCR (2014a) GCSE Religious Studies B (Philosophy and Applied Ethics) Unit B601: Philosophy of Religion 1 General Certificate of Secondary Education Mark Scheme for June 2014. [online] Available at http://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/240140‐mark‐scheme‐unit‐b601‐philosophy‐1‐deity‐religious‐andspiritual‐experience‐end‐of‐life‐june.pdf [accessed 16/05/19].

- OCR (2014b) GCSE Religious Studies B (Philosophy and Applied Ethics) Unit B602: Philosophy of Religion 2 General Certificate of Secondary Education Mark Scheme for June 2014. [online] Available at http://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/240141‐mark‐scheme‐unit‐b602‐philosophy‐2‐good‐and‐evilrevelation‐science‐june.pdf [accessed 16/05/19].

- OCR (2014c) GCSE Religious Studies A and B (Philosophy and Applied Ethics) Unit B603: Ethics 1: (Relationships, Medical Ethics, Poverty and Wealth) General Certificate of Secondary Education Mark Scheme for June 2014. [online] Available at http://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/240083‐mark‐schemeunit‐b603‐ethics‐1‐relationships‐medical‐ethics‐poverty‐and‐wealth‐june.pdf [accessed 16/05/19].

- OCR (2014d) GCSE Religious Studies A and B (Philosophy and Applied Ethics) Unit B603: Ethics 1: (Relationships, Medical Ethics, Poverty and Wealth) General Certificate of Secondary Education Mark Scheme for June 2014. [online] Available at http://www.ocr.org.uk/Images/240142‐mark‐schemeunit‐b604‐ethics‐2‐peace‐and‐justice‐equality‐media‐june.pdf [accessed 16/05/19].

- Ofqual (2013) GCSE Reform Consultation ‐ June 2013: Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar. [online] Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/529371/2013-06-11-gcse-reform-consultation-june-2013.pdf/ [accessed 15/05/19].

- Ofqual (2015) Regulations for the Assessment of the Quality of Written Communication. [online] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/446030/regulations-for-the-assessment-of-the-quality-of-written-communication.pdf [accessed 15/05/19].

- Wilson, A. C. and Myhill, D. A. (2012) Ways with words: Teachers’ personal epistemologies of the role of metalanguage in the teaching of poetry writing. Language and Education 26: 553‐68.

The biggest impact of Gatsby has been to act as a framework on which we have built our brand new Striding Out programme, which embraces the concept of a truly holistic approach to career and higher education preparation.

The biggest impact of Gatsby has been to act as a framework on which we have built our brand new Striding Out programme, which embraces the concept of a truly holistic approach to career and higher education preparation.

Alongside high-quality provision in lessons, the academic stretch programme challenges our learners throughout the school.

Alongside high-quality provision in lessons, the academic stretch programme challenges our learners throughout the school. Our robust Explore and Rosewell lecture series welcomes external speakers to challenge and provoke those girls in Years 9 to 13 to think more deeply both within and without their subject specialism. Parents, teachers and partner schools are welcome at these lectures. Our external speakers have included: Janet Henry, Chief Global Economist for HSBC, “Diverging fortunes”; “In conversation with” Gillian Clark, poet, playwright,

Our robust Explore and Rosewell lecture series welcomes external speakers to challenge and provoke those girls in Years 9 to 13 to think more deeply both within and without their subject specialism. Parents, teachers and partner schools are welcome at these lectures. Our external speakers have included: Janet Henry, Chief Global Economist for HSBC, “Diverging fortunes”; “In conversation with” Gillian Clark, poet, playwright,  editor, broadcaster; Prof Vicky Neale, Whitehead lecturer at the Mathematical Institute, “Closing the Gap, the quest to understand prime numbers”; Dr Guy Sutton, “Mind and brain in the 21st Century”.

editor, broadcaster; Prof Vicky Neale, Whitehead lecturer at the Mathematical Institute, “Closing the Gap, the quest to understand prime numbers”; Dr Guy Sutton, “Mind and brain in the 21st Century”.

A discussion of “The Lazy Teacher’s Handbook” by Jim Smith drew the following comments:

A discussion of “The Lazy Teacher’s Handbook” by Jim Smith drew the following comments: “Independent Thinking” by Ian Gilbert elicited the following:

“Independent Thinking” by Ian Gilbert elicited the following: