Charlotte Moon, who teaches English here at WHS, looks to investigate issues around how we can encourage children to continue reading, increasing their independence.

When do we stop reading with our children?

As babies and toddlers, we read to our children to stimulate and satisfy their curiosity, to promote language acquisition, and as a way of bonding. Of course, they can’t even recognise the alphabet at this stage, so the actual reading bit naturally devolves on us. By kindergarten and reception, children begin learning to read for themselves, most likely with the structured support of a reading scheme followed by their school. At this stage, there is an understanding between parent and school that developing your child’s reading ability is a shared responsibility; your child will read with support at school, learning phonics and so forth, and will have books and reading logs sent home with the expectation that parents will initiate and supervise ‘reading homework’ most days of the week.

So what changes as our children progress through primary education?

By the time they’ve moved up to Year 7, what proportion of parents are still actually reading with or to their kids on a regular basis? As an English teacher, the impression I get is that there is a definite shift which correlates with children being able to read independently. Why read to or with your child when they can read to themselves, right? There don’t seem to be enough hours in the day for parents to satisfy the demands placed upon us, so no longer having to supervise reading homework may come as a welcome relief.

The problem is, without supervision, encouragement and the bonding that comes through shared reading, children face the danger of entering a reading wasteland at this age (and I don’t mean that their new found reading independence miraculously enables them to read T.S. Eliot). Do we really know how often or how much they are reading? Do we even know what they’re reading? At Key Stage 3 (Years 7-9), students at WHS read a book they have chosen independently for 10 minutes at the beginning of each double lesson, but in some cases the level of challenge in these books varies greatly: in the same class, one student might be reading Pride and Prejudice while another reads Jacqueline Wilson. It is here, too, that the shared responsibility between school and parent can seem less distinct. While schools offer reading lists and take an interest in which books their students bring to lessons, we no longer have the time to sit and read with students individually, or to take remedial groups out of lessons for extra reading support. And when it comes to the co-curricular provision on offer for English, it tends to be the way that the keenest readers and writers are the ones who attend, and the students who shy away from reading keep their distance.

Jacqueline Wilson and Jane Austen: The variation in level of challenge in reading can be very apparent in KS3 lessons.

How do I get her to read?

As students approach the age of having to sit public exams, the common question at parents’ evening is ‘how do I get her to read?’. Parents can seem at a loss as to how to influence or encourage their daughter’s reading once she has entered adolescence. My guess is that very few parents are reading with their daughters by this stage, but are also, understandably, keen for their daughters to be making good progress and keeping up with their cohort in terms of attainment. So why not read with your child? It could improve her confidence, develop her understanding of texts and aid her continuing language acquisition. Not to mention, at any age, reading is still a fantastic way to bond with your child. So, what’s stopping us? Is it still the restraints on our time, or is it the fear of incurring a teenage meltdown that would impress even Harry Enfield’s ‘Kevin’? Can we build a meaningful relationship based on reading once our children enter their teens? Can we bridge the gap that has been created by years of leaving them to read independently?

Every parent-child dynamic is different. But why not try reading with your teenager? It really will help develop their skills and understanding as readers and writers, and it will enable you to connect, or even reconnect with them, on a level other pastimes cannot necessarily replicate. Model the reading you want to see in your child and you will both reap the benefits.

What is it that renders Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights simply better novels than Twilight?

What is it that renders Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights simply better novels than Twilight? We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years.

We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years. The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’

The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’

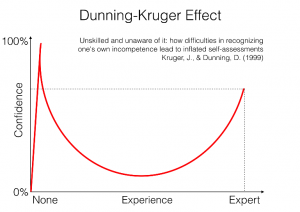

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience:

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience: