Head of Year 7 Jenny Lingenfelder reflects on encouraging emotional agility during the ‘transition’ phase from Year 6 into Year 7.

We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years.

Even for the majority who are eagerly awaiting the increased independence and exciting changes ahead, transition from primary to secondary school is well known to come with its challenges – both academically and emotionally. One aspect we have been focusing on in the Year 7 pastoral team is that of emotional agility and how to resolve conflict when the ‘friendship issues’ emerge once they have settled in. These are a common and developmentally crucial feature of adolescent life and so our focus is primarily how to navigate them effectively.

Brene Brown’s research into shame and vulnerability over the past twenty years is insightful and brings a wealth of authentic guideposts which can be easily adapted for pastoral care. The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’[1] focuses on how we build shields up to protect ourselves from feeling vulnerable such as perfectionism, foreboding joy, playing the victim or the Viking to name but a few. Traits we as adults can all recognise but which start to emerge when we are in the playground. Her strategies to break down these shields include practising gratitude, appreciating the beauty in the cracks, setting boundaries, cultivating connection, being present and moving forward all of which resonate deeply with our pastoral vision at WHS for our young girls in today’s society.

All well and good but how does this work in practice?

Nicola Lambros’ contribution to the GL Assessment Children’s Wellbeing report[2] this year clearly lays out the correlation between wellbeing and impact on learning. Whilst genuinely complimenting schools on their support for the mental health of their students, she compares some of this help to that of taking paracetamol for a headache – whilst alleviating the pain, it doesn’t help uncover the underlying causes. She has a point. So how do we avoid putting a plaster over these issues? How do we bring about a deep, raw and authentic cultural shift in how we manage teenage behaviour in an ever increasingly sexualised, intrusive and pressurised society where comparison is the killjoy of creativity? How do we go about ensuring the girls develop emotional agility from a young age? And develop self-efficacy which is authentic and whole-hearted, a firm foundation for the teenage years and life in general?

Big questions, but ones we relish in the Year 7 team, especially with the knowledge that scientific research has now proven that the teenage brain has a further burst of growth at this time allowing for the reprogramming of those learnt behaviours which were previously thought of as hardwired and unchangeable. With this understanding, it is an exciting prospect to know we can equip our girls from an early stage with the tools on how to be emotionally agile throughout their teenage years and beyond.

Here are some reflections outlining where we are seeing some fruit:

- Practising proactive intervention. When a friendship issue arises, at times getting those involved around the table for a mediation is the best option. It’s uncomfortable (initially) but that vulnerability enables authentic conversation, breaks down walls and provides a way of moving away from blame and forging a pathway forward. Another strategy we have used is the ‘Support Group Method’ which encourages collective responsibility: with the individual’s permission, spilt the form into small groups, share what the problem is and ask for ideas on how to move forward. Getting students to write down their ideas and pop in a box enables more freedom of thought.[3]

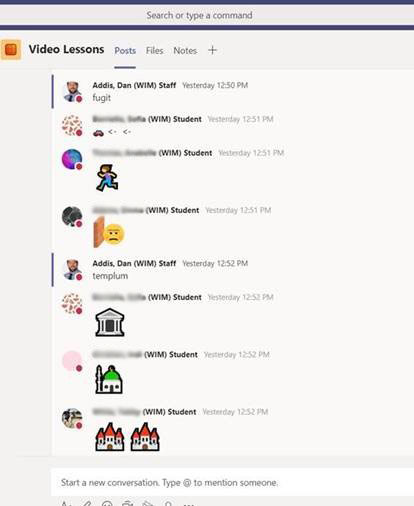

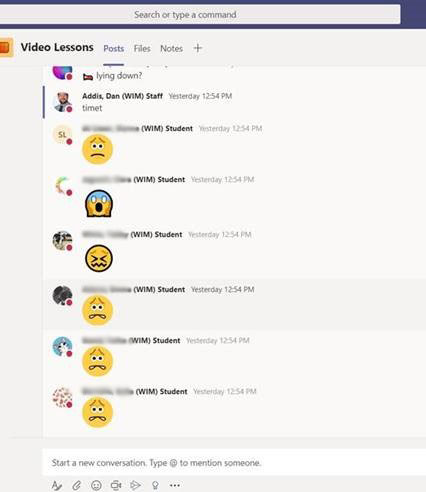

- The not so nice emotions and how we describe them. Psychologist Susan David in her TED talk ‘the gift and power of emotional courage’[4] maintains ‘tough emotions are part of our contract with life’ and more poignantly ‘discomfort is the price of admission to a meaningful life’. Enabling girls to experience this on their level with a friendship fallout is crucial in helping them develop emotional intelligence. She also stresses that we own our emotions, they don’t own us. So, rather than ‘I am stressed’ using the phrases ‘I’m noticing’ and ‘I’m feeling’ can help embed emotional agility in the long term.

- Use of coaching methods. Whether in PSHE lessons or pupil meetings these can equip girls with tools to reach their full potential and prevent bad habits from setting in early. Top performance coach Sara Milne Rowe’s new book ‘The Shed Method- Making Better Choices When It Matters’[5] is illuminating on this topic. She maintains ‘mind energy is the fuel that fires our brilliant human brain and is at the heart of building any new habit- be it a body habit, mood habit or mind habit’ and provides practical examples of how to set goals and achieve them; strategies which can be translated easily into the school setting.

- Listen to pupil voice. Whether it is touching base after the first couple of weeks, canvassing opinions on the Year 7 PHSE programme or at the end of a term, we ask our Year 7 girls for feedback regularly which helps enormously to know what is really going on during this phase. One notable occasion is asking the girls to nominate who and why they want to give the Speech Day ‘Grit’ Awards to in the year group. Reading the nominations has each year brought me both to tears and chuckles and reminds me that we wouldn’t have known about the small acts of kindness or bravery that happen on a daily basis unless we asked our girls to tell us.

- Thinking creatively. We took Year 7 to see Wicked this year and have incorporated the story into how to approach friendship issues and ideas around acceptance in the wider world. The staff enjoy this just as much as the girls!

It’s an organic and evolving process and one that excites me greatly. Sometimes ensuring a smooth transition process does require a paracetamol or a plaster. However, building emotional agility takes time and effort to adopt as a habit. It is not (as is often perceived) the case of putting on resilient armour reading for battle. Vulnerability is at the core of this approach and that takes real courage. But it is worth it and I feel privileged to work in a place where girls and staff are willing to give it a go.

Jenny Lingenfelder, Head of Year 7

[1] Brene Brown ‘Daring Greatly. How the Courage to be Vulnerable Transforms the Way we Live, Love and Parent and Lead’, 2012

[2] GL Assessment Children’s Wellbeing: Pupil Attitudes to Self and School Report 2018

[3] See Ken Rigby University of South Australia for more detailed information on different intervention approaches, March 2010

[4] Susan David TED talk ‘The Gift and Power of Emotional Courage’, Nov 2017 https://www.ted.com/talks/susan_david_the_gift_and_power_of_emotional_courage

[5] Sara Milne Rowe ‘The SHED METHOD Making Better Choices When it Matters, 2018