Our sport stars of the week are the WHS basketball team. After successfully competing in the Merton Borough tournament they became Borough Champions!

A huge congratulations for this achievement.

Our sport stars of the week are the WHS basketball team. After successfully competing in the Merton Borough tournament they became Borough Champions!

A huge congratulations for this achievement.

Morning everyone, I hope you had a lovely weekend, just a few sports notices from me.

Our rowers performed very well on Sunday at Weybridge. There was gold in the women junior U17 doubles, gold in the U16 and silver in the U15 among other encouraging results too.

On Saturday 16 WHS netball teams played against Latymer school and won the majority of matches with a 10:6 ratio.

Our U13 gym squad came 5th out of 15 at the Surrey floor and vault competition. Congratulations to all girls who participated.

Our sports team of the week is our Basketball team as they won the Merton Borough tournament and are now Borough Champions!

I hope you all have a lovely week.

Inspirational sports person: Serena Williams

This week’s inspirational sports person is Serena Williams. I have chosen her because of her journey to become one of the world’s greatest tennis players. She is widely known and has worked immensely hard in order to get where she is today. She has 4 Olympic gold medals and 4 Grand Slams to her name, and won sports-person of the year by the magazine ‘Sports Illustrated’. The reason she is such an inspiration to me is because throughout her journey despite having received racism and sexism from fans and tennis administrators, she is still so strong and it takes a lot of mental strength to overcome these challenges and use them positively in order to make you, and your game stronger.

Additionally, in the recent US Open in September 2018 she called out a double-standard and challenged the way society thinks women should behave when playing sport in comparison to men. During the finals match against Osaka, Williams received a code violation for racquet abuse (hitting her racquet on the floor), but as later summarised in an interview “when a woman is emotional, she’s ‘hysterical’ and she’s penalised for it. When a man does the same, he’s ‘outspoken’ and there are no repercussions”. I think that she is an inspiration, not only to sport players but to all people out there.

Emily Ng,

Swimming rep

Hi everyone,

I hope you all had a lovely holiday and are enjoying the first few weeks of January. In the spring term, we welcome the netball season and with multiple teams across year groups it promises to be a busy and successful season.

Congratulations to all girls who participated in hockey teams last season. Every player showed determination and development in their skills which was represented in the strong results we had. I hope you had some well-deserved rest over the holidays and continue playing hockey with your clubs and county ahead of next year.

Our rowing teams had their first training session of 2019, with excellent coaching and great teamwork they are a force to be reckoned with! We wish you lots of luck for this year and we are sure it will be an even stronger season!

Good luck to our basketball team who are currently competing in the Merton borough tournament.

Enjoy your week and well done to all the girls who took mocks after Christmas!

Annie Drummond,

Sports Captain

Jenny Cox, Director of Co-curricular and Partnerships at Wimbledon High, looks at the links between co-curricular activities and the impact these can have on academic outcomes in the classroom.

There has been much research over the years investigating the link between Sport and its benefits – not only to a healthy lifestyle – but to the academic progress of students in schools and universities. Research has shown that regular physical activity leads to improvements in a range of cognitive functions, including information processing, attention and executive function (Chaddock et al. 2011). However, does involvement in any co-curricular club facilitate academic outcomes?

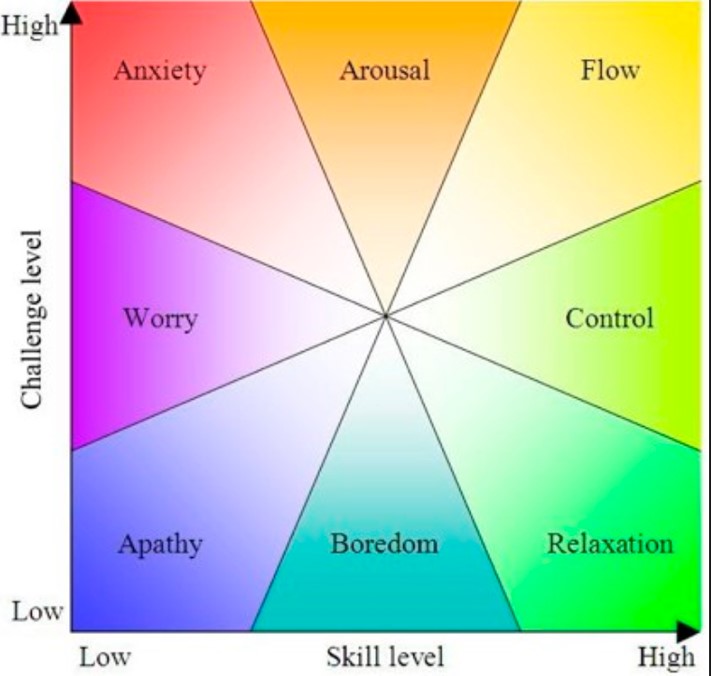

Can you think of a time when you have ever been so absorbed in an activity that you have completely lost track of time? That whatever you were doing was challenging, totally captivating, was extending your skills and you were virtually operating in the subconscious? If you can, it’s likely that you were experiencing a phenomenon known as ‘flow’. Psychologist Csikszentmihalyi writing in the 1960s researched this initially with it really coming to the forefront of sports psychology in the 1990s.

He described it as:

“A deeply rewarding and optimal experience characterised

by intense focus on a specific activity

to the point of becoming totally absorbed in it”

Csikszentmihalyi suggested that experiencing ‘flow’ makes us happier and more successful, which in turn leads to increased performance. To get to this point, he pointed out that tasks have to be constantly challenging which in turn results in personal growth and development. This doesn’t mean that we always have to be in a state of optimal performance, but more that we are fully immersed in the process of the task in hand, as shown in the diagram below:

‘Flow’ experiences can happen as part of everyday life, and Csikszentmihalyi suggested overlearning a concept or a skill can help people experience flow. Within a sporting context, it is sometimes referred to a “being in the zone”, experiencing a loss of self-consciousness and feeling a sense of complete mastery.

In addition to overlearning, another key component of finding ‘flow’ is doing activities that we are intrinsically motivated to take part in. This means work and activities that we feel real meaning behind and enjoy doing for the sake of doing. Financial gain, awards and praise can be by-products of the ‘flow’ activities you do, but they cannot be the core motivation behind what you’re doing. Csikszentmihalyi even goes further, saying the feeling should be “such that often the end goal is just an excuse for the process.”

So why is this relevant to our school co-curricular programme and can it be linked to academic success? The links here are two-fold.

Firstly, the co-curricular programme is designed to inspire and enhance the general learning of new skills and concepts. It gives us more time to focus on over-learning a skill or concept because there is no pressure of being examined, therefore no exact specification or course content to get through. We have the luxury of taking our time, over-rehearsing, over practising to a point of taking part in an activity with a loss of sub-consciousness. We may repeat skills so frequently because we revisit them two, three, four, seven, eight times a week, (think of rowing, drama, and music to name just three activities that have repeat weekly sessions), that the feeling of knowing a skill, a sequence, a technique really well and performing is sub-consciously really does happen.

Secondly, with this feeling of ‘flow’ comes those ‘magic moments’ we can all benefit from at any point during the day. The mere fact we are immersed in activity we enjoy could result in us being ‘in the zone’. We are busy immersed in something which is likely to mean we are automatically not thinking about an essay, a grade, a piece of coursework, a friendship or relationship issue at that time and so as a consequence that time contributes enormously to our state of well-being and happiness. This, in turn, is highly likely to lead to a more productive ‘head space’ for work when we return to it, less procrastinating, greater focus and possibly better outcomes.

So can we draw a link between participation in co-curricular activities and academic outcomes? There is research to indicate we can….. happy reading!

–

Matilda, Year 13, investigates the links between romance languages and music to discover whether the learning of one can help in the understanding of the other.

It is often said that music is the ‘universal language of mankind’, due to its great expressive powers which have the ability to convey sentiments and emotions.

But what are the connections between music and languages?

A romance language is a language derived from Latin and this group of languages has many similarities in both grammar and vocabulary. The 5 most widely spoken romance languages are Spanish (with 470 million speakers), Portuguese, French, Italian and Romanian.

There are 3 main connections between languages and music:

There is a link between languages and music in remembering words. This is shown in a study where words were better recalled when learned as a song rather than a speech. This is because melody and rhythm give the memory cues to help recall information.[1]

The British anthropologist and evolutionary psychologist who specialises in primate behaviour, Robin Dunbar, says that music and language help to knit people together in social groups. This is because musicians process music as a language in their heads. Studies have shown the planum temporal in the brain is active in all people whilst listening to music.

However, in non-musicians, the right-hand side was the most active, meanwhile, in musicians, the left side dominated, this is the side believed to control language processing. This shows that musicians understand music as a language in their brain.

In another study, scientists analysed the Broca’s area, which is crucial in language and music comprehension. It is also responsible for our ability to use syntax. Research has shown the in the Broca’s area of the brain, musicians have a greater volume of grey matter, suggesting that it is responsible for both speech and music comprehension.

Both music and languages share the same building blocks as they are compositional. By this, I mean that they are both made of small parts that are meaningless alone but when combined can create something larger and meaningful.

Both music and languages share the same building blocks as they are compositional. By this, I mean that they are both made of small parts that are meaningless alone but when combined can create something larger and meaningful.

For example, the words ‘I’, ‘love’ and ‘you,’ do not mean much individually, however, when they are constructed in a sentence, carry a deep sentimental value. This goes the same for music notes, which when combined can create a beautiful, purposeful meaning.

Musical training has been shown to improve language skills.[2] In a study carried out in 2011, developmental psychologists in Germany conducted a study to examine the relationship between development of music and language skills. In the experiment, they separated children aged 4 into 2 groups, 1 of these groups receiving musical training, and one did not.

Later on, they measured their phonological ability (the ability to use and manipulate language) and they discovered the children who had received music lessons were better at this. Therefore, this shows that learning and understanding language can go hand in hand with musical learning and ability.

–

References:

[1] See https://www.theguardian.com/teacher-network/2018/mar/14/sound-how-listening-music-hinders-learning-lessons-research

[2] See https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/the-athletes-way/201806/how-does-musical-training-improve-language-skills

Holly Beckwith, Teacher of History and Politics at WHS, explains how the History and English departments are using a small-scale action research project to try and rethink the way in which analytical writing is taught at Key Stage 3.

The age-old question for history teachers: how do we get our pupils to produce effective written analysis? It is a question we regularly grapple with as a department. Constructing and sustaining arguments is at the centre of what we do as Historians and analytical writing is thus at the core of our teaching of the discipline. But it has not always been an easy task for history practitioners to get pupils to achieve this, even over a whole key stage.

Through published discourse, history teachers have explored the ways in which we can teach pupils to produce argued causal explanations in writing (Laffin, 2000; Hammond, 2002; Chapman, 2003; Counsell, 2004; Pate and Evans, 2007; Fordham, 2007). Extended writing has been seen as an important pedagogical tool in developing pupils’ causal reasoning as it necessitates thinking about the organisation, arrangement and relative importance of causes.

In 2003, History teacher Mary Bakalis theorised pupils’ difficulty with writing as a difficulty with history. She posited that writing is both a form of thinking and a tool for thinking and, therefore, that historical understanding is shaped and expressed by writing. Rather than viewing writing as a skill that one acquires through history, Bakalis saw writing as part of the process of historical reasoning and thinking. Through an analysis of her own Year 7 pupils’ essays, she noticed that pupils had often failed to see the relevance of a fact in relation to a question. She realised that pupils thought that history was merely an activity of stating facts rather than using facts to construct an argument.

As a solution to similar observations in pupils’ writing, history teachers have used various forms of scaffolding to help pupils construct arguments. This includes the well-known PEE tool, which was advocated by genre theorists and cross-curricular literary initiatives as put forward by, for example, Wray and Lewis (1994), and has since been used widely in History and English departments nationwide, including ours at Wimbledon High. The concept of PEE (point, evidence, explanation) is simple and therefore a helpful tool for teaching paragraph structure. It gives pupils security in knowing how to organise their knowledge on a page.

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

But while PEE in theory offers a sound approach to structuring extended writing in history, it has been criticised for unintentionally removing important steps in historical thinking. Fordham, for example, noticed that the use of such devices in his practice meant that there was too much ‘emphasis on structured exposition [which] had rendered the deeper historical thinking inaccessible’ (Fordham, 2007.) Pate and Evans similarly argued that ‘historical writing is about more than structure and style; the construction of history is about the individual’s reaction to the past’ (Pate and Evans, 2007). Therefore, too much emphasis on the construction of the essay rather than the nuances of an argument or an engagement with other arguments, as Fordham argues, can create superficial success. Further problems were identified by Foster and Gadd (2013), who theorised that generic writing frame approaches such as the PEE tool was having a detrimental effect on pupils’ understanding and deployment of historical evidence in their history writing.

After reflecting on this research conducted by History teachers as a department, we started to consider that encouraging our pupils to use structural devices to help pupils’ historical writing may not be very purposeful if divorced from getting pupils to see the function and role of arguments in the discipline of history itself. Through discussions with the English department, who have also used the PEE tool in their teaching, we realised we shared similar concerns.

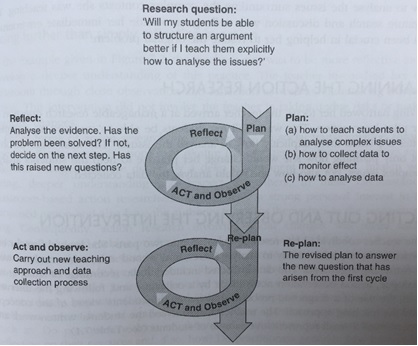

Not satisfied with simply holding these, we decided to do something about it and have since embarked on a piece of action research with the English department. Action research is interested in finding solutions to problems to produce better outcomes in education and involves a continual cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection such as Figure 2 below illustrates.

We started our first cycle of our piece of small-scale research last term teaching analytical writing to classes using two different lesson sequences: one which teaches pupils PEE and one which omits this.

We then compared the writing produced by these classes to identify any noticeable differences and structured our reflections around four questions:

1. How has the experience of teaching and learning been different to previous experience, and why?

2. How have students responded to the new method?

3. How far has the intervention resulted in a different approach to analytical writing so far?

4. What are our next steps – what went well, and what needs adjusting?

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

Thus far, the comparisons have allowed us to make some tentative observations. Whilst these do not seem to show an established pattern yet, there does seem to be a greater sense of originality and creativity in some of the non-PEE responses. Pupils seemed to produce more free-flowing ideas and were making more spontaneous links between those ideas, showing a higher quality of thinking. In addition, a few of the participating teachers noticed that their questioning became more tailored to developing the ideas and thinking of the pupils they taught rather than getting them to write something particular. However, others noticed that pupils were already well versed in PEE and so the change in approach may have had less of an effect. Other pupils seemed to feel less secure with a freeform structure. In order to encourage the more positive effects, our next cycle of teaching will experiment with different ways of planning essays that provide pupils with a way of organising ideas more visually and focus on the development of our questioning to further develop the higher quality thinking we noticed with some classes.

The first research cycle has thus been a worthwhile collaborative reflection on our teaching practice in the pursuit of improving our pupils’ historical and literary analysis. It has given us some insights which we’re looking to develop further as we head into the second term of the academic year.

–

Jo, Year 13, explores what is happening chemically inside the brains of those suffering from eating disorders and shows how important this science is to understanding these mental health conditions.

The definition of an eating disorder is any range of psychological disorders characterised by abnormal or disturbed eating habits. Anorexia is defined as a lack or loss of appetite for food and an emotional disorder characterised by an obsessive desire to lose weight by refusing to eat. Bulimia is defined as an emotional disorder characterised by a distorted body image and an obsessive desire to lose weight, in which bouts of extreme overeating are followed by fasting, self-induced vomiting or purging. Anorexia and bulimia are often chronic and relapsing disorders and anorexia has the highest death rate of any psychiatric disorder. Individuals with anorexia and bulimia are consistently characterised by perfectionism, obsessive-compulsiveness, and dysphoric mood.

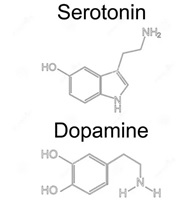

Dopamine and serotonin function are integral to both of these conditions; how does brain chemistry enable us to understand what causes anorexia and bulimia?

Dopamine is a compound present in the body as a neurotransmitter and is primarily responsible for pleasure and reward and in turn influences our motivation and attention. It has been implicated in the symptom pattern of individuals with anorexia, specifically related to the mechanisms of reinforcement and reward in engaging in anorexic behaviours, such as restricting food intake. Dysfunction of the dopamine system contributes to characteristic traits and behaviours of individuals with anorexia which includes compulsive exercise and pursuit of weight loss.

In people suffering from anorexia dopamine levels are stimulated by restricting to the point of starving. People feel ‘rewarded’ by severely reducing their calorie intake and in the early stages of anorexia the more dopamine that is released the more rewarded they feel and the more reinforced restricting behaviour becomes. Bulimia involves dopamine serving as the ‘reward’ and ‘feel good’ chemical released in the brain when overeating. Dopamine ‘rushes’ affect people with anorexia and bulimia, but for people with anorexia starving releases dopamine, whereas for people with bulimia binge eating releases dopamine.

Serotonin is responsible for feelings of happiness and calm – too much serotonin can produce anxiety, while too-little may result in feelings of sadness and depression. Evidence suggests that altered brain serotonin function contributes to dysregulation of appetite, mood, and impulse control in anorexia and bulimia. High levels of serotonin may result in heightened satiety, which means it is easier to feel full. Starvation and extreme weight loss decrease levels of serotonin in the brain. This results in temporary alleviation from negative feelings and emotional disturbance which reinforces anorexic symptoms.

Tryptophan is an essential amino acid found in the diet and is the precursor of serotonin, which means that it is the molecule required to make serotonin. Theoretically, binging behaviour is consistent with reduced serotonin function while anorexia is consistent with increased serotonin activity. So decreased tryptophan levels in the brain, and therefore decreased serotonin, increases bulimic urges.

Distorted body image is another key concept to understand when discussing eating disorders. The area of the brain known as the insula is important for appetite regulation and also interceptive awareness, which is the ability to perceive signals from the body like touch, pain, and hunger. Chemical dysfunction in the insula, a structure in the brain that integrates the mind and body, may lead to distorted body image, which is a key feature of anorexia. Some research suggests that some of the problems people with anorexia have regarding body image distortion can be related to alterations of interceptive awareness. This could explain why a person recovering from anorexia can draw a self-portrait of their body image that is typically 3x its actual size. Prolonged untreated symptoms appear to reinforce the chemical and structural abnormalities in the brains seen in those diagnosed with anorexia and bulimia.

Therefore, in order to not only understand and but also treat both anorexia and bulimia, it is central to look at the brain chemistry behind these disorders in order to better understand how to go about successfully treating them.

Phoebe, Year 13, explores the use of Bitcoin as a currency and its potential to replace Sterling by discussing the limitations of the new currency.

Bitcoin is a cryptocurrency, which is a digital currency that uses cryptography for security, and a worldwide payment system. It is the first decentralized digital currency, meaning the system works without a central bank or single administrator. It is based on a special field of maths called cryptography which is the study of how to secure communications, this being one of the main issues with not having transactions being overseen by a central administrator. Bitcoins are created through the process of mining; where miners use special software to solve mathematical problems and are issued in exchange with bitcoins. So, to what extent does this new unregulated technology have the ability to replace sterling?

Despite the fact that Bitcoin supports the attractive libertarian utopia of a society free from government intervention, where welfare is cheaper and wealth more distributed, in reality Bitcoin currently does not pose a threat to the sterling. One of the major reasons that I will be focusing on is the unsustainable scale of computer computational power that is required in order for miners to verify transactions within the block chain system due to the increasing marginal costs for them. Miners are being imposed with a direct cost as they are forced to require more bandwidth to enable them to solve the increasingly difficult puzzles in the same time frame.

Distributed systems such as Bitcoin’s involve a negative externality that causes over investment in computer hardware as the expected marginal revenue from the individual miners is increasing with the amount of computing power that they individually have. Not only does this increase their own marginal cost but it increases the competition within the system and thus the cost is also increasing across the entire network. “Cetirus paribus” economic theory would suggest that in equilibrium all miners are inefficiently investing in hardware while receiving the same revenue that they would have had they not invested in the extra computing power. This behaviour is irrational as it is increasing the computing power across the entire network making it harder for them to succeed individually.

Distributed systems such as Bitcoin’s involve a negative externality that causes over investment in computer hardware as the expected marginal revenue from the individual miners is increasing with the amount of computing power that they individually have. Not only does this increase their own marginal cost but it increases the competition within the system and thus the cost is also increasing across the entire network. “Cetirus paribus” economic theory would suggest that in equilibrium all miners are inefficiently investing in hardware while receiving the same revenue that they would have had they not invested in the extra computing power. This behaviour is irrational as it is increasing the computing power across the entire network making it harder for them to succeed individually.

If the cost of verification for the miners is constantly increasing, then eventually the incentive to secure the network will disappear and lead to the collapse of the system.

Therefore, due to this increasing cost of mining, Bitcoin, in its current state, does not have the potential to replace sterling.

Clare Roper, the Director of Science, Technology and Engineering at WHS explores the world of big data. As teachers should we be aware of big data? Why, and what data is being collected on our students every day… but equally relevant questions about how we could increase awareness of the almost unimaginable possibilities that big data might expose our students to in the future.

The term ‘big data’ was first included in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2013 where it was defined as “extremely large data sets that may be analysed computationally to reveal patterns, trends, and associations.”[1] In the same year it was listed by the UK government as one of the eight great technologies that now receives significant investment with the aim of ensuring the country is a world leader in innovation and development.[2]

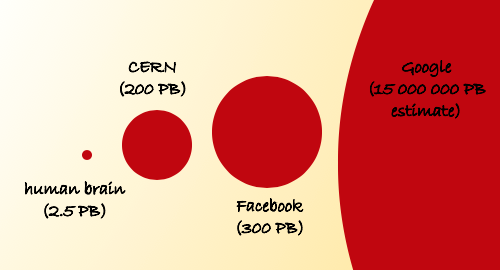

‘Large data sets’ with approximately 10000 data points in a spreadsheet have recently introduced into the A Level Mathematics curriculum, but ‘big data’ is on a different scale entirely with the amount of data expanding at such speed, that it cannot be stored or analysed using traditional methods. In fact, it is predicted that between 2012 and 2020 the global volume of data will increase exponentially from 4.4 zettabytes to 44 zettabytes (ie. 44 x1021 bytes)[3] and data scientists now talk of ‘data lakes’ and ‘dark data’ (data that you do not know about).

But should we be collecting every piece of data imaginable in the hope it might be useful one day, and is that even sustainable or might we be sinking in these so-called lakes of data? Many data scientists argue that data on its own actually has no value at all and that it is only when it is analysed in context that it becomes valuable. With the introduction of GDPR in the EU, there has been a lot of focus on data protection, data ethics and the ownership and security of personal data.

At a recent talk at the Royal Institute, my attention was drawn to the bias that exists in some big data sets. Even our astute Key Stage 3 scientists will be aware that if the data you collect is biased, then inevitably any conclusions drawn from it will at best be misleading, but more likely, be meaningless. The same premise applies to big data. The example given by Maja Pantic from the Samsung AI Lab in Cambridge, referred to facial recognition, and the cultural and gender bias that currently exist within some of the big data behind the related software – but this is only one of countless examples of bias within the big data on humans. With more than half the world’s population online, digital data on humans makes up the majority of a phenomenal volume of big data that is generated every second. Needless to say, those people who are not online are not included in this big data, and therein lies the bias.

There are many examples in science where the approach to big data collection has been different to that collected on humans (unlike us, chemical molecules do not generate an online footprint by themselves) and new fields in many sciences are advancing because of big data. Weather forecasting and satellite navigation rely on big data and new technologies have emerged including astroinformatics, bioinformatics (boosted even further recently thanks to an ambitious goal to sequence the DNA of all life – Earth Biogenome project ), geoinformatics and pharmogenomics to name just a few. Despite the fact that the term ‘big data’ is too new to be found in any school syllabi as yet, here at WHS we are already dabbling in big data (eg. MELT project, IRIS with Ark Putney Academy, Twinkle Orbyts, UCL with Tolcross Girls’ and Tiffin Girls’ and the Missing Maps project).

To grapple with the idea of the value of big data collections and what we should or should not be storing and analysing, I turned to CERN (European Organisation of Nuclear Research). They generate millions of collisions every second from the Large Hadron Collider and therefore will have carefully considered big data collection. It was thanks to the forward thinking of the British scientist, Tim Berners-Lee at CERN that the world wide web exists as a public entity today and it seems scientists at CERN are also pioneering in their outlook on big data. Rather than store all the information from every one of the 600 million collisions per second (and create a data lake), they discard 99.99% of this data as it is produced and only store data for approximately 100 collisions per second. Their approach is born from the idea that although they might not know what they are looking for, they do know what they have already seen [4]. Although CERN is not using DNA molecules for the long-term storage of their data yet, it seems not so far-fetched that one of a number of new start-up companies may well make this a possibility soon. [5]

None of us know what challenges lie ahead for ourselves as teachers, nor our students as we prepare them for careers we have not even heard of, but it does seem that big data will influence more of what we do and invariably how we do it. Smart data, i.e. filtered big data that is actionable, seems a more attractive prospect as we work out how balance intuition and experience over newer technologies reliant on big data where there is a potential for us to unwittingly drown in the “data lakes” we are now capable of generating. Big data is an exciting, rapidly evolving entity and it is our responsibility to decide how we engage with it.

[1] Oxford Dictionaries: www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition//big-data, 2015.

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/eight-great-technologies

[3] The Digital Universe of Opportunities: Rich Data and the Increasing Value of the Internet of Things, 2014, https://www.emc.com/leadership/digital-universe/

[4] https://home.cern/about/computing

[5] https://synbiobeta.com/entering-the-next-frontier-with-dna-data-storage/