Miss Lucinda Gilchrist, Head of English, considers the virtues of being ‘stuck’, and how this can help pupils tackle challenging tasks with more confidence.

A growth mindset and being ‘stuck’

Carol Dweck’s influential work on growth mindset has become common parlance across schools now, and we know that helping pupils develop grit, perseverance and resilience is key to supporting them in their learning. A growth mindset is one in which ability is seen as ‘changeable’, and which ‘can be developed through learning’ (Dweck, 2006), rather than innate or fixed. As teachers, we want pupils to be able to reframe their thinking about things they struggle with to develop a growth mindset. We therefore provide scaffolds and supports to ease pupils into the ‘zone of proximal development’ and enable them to see smaller successes on the path to larger ones.

However, small and incremental scaffolds may actually serve to make them more reliant on the support from their teachers than on their own reasoning. An example of this: as part of some of my MA action research, I declared ‘war’ on the PEE/PEA structure, which I knew pupils had become too reliant on and which was making their writing too mechanical, and many of them simply relied on another acronym they had learnt in the past. By easing pupils into a task too gently, we run this risk: ‘if a task does not puzzle us at all, then it is not a problem; it is just an exercise’[1].

We therefore sometimes need to remove even more of the support structures, and defamiliarise pupils even further in order to make them less reliant on the scaffolds we put in place, and make them more aware of the ways in which they can get themselves unstuck, helping them to understand what to do when they don’t know what to do. We can expose them to challenges which they might consider beyond their ‘zone of proximal development’ – be this a new style of Mathematics problem, an unusual context for a theory in the Sciences, or a piece of music unlike anything they’ve heard before.

An example from English – analysing ‘unseen’ texts

Many students of English Literature at KS4 are anxious about the concept of ‘unseen’ – the part of the examination where pupils have to write an essay about a text they have never seen before. It’s particularly challenging with poetry: a poem is often by nature oblique and abstract, resisting an easy answer. While this is what we love about poetry, it can be frustrating for some pupils who want the ‘right’ answer! Pupils who find developing their own interpretations of texts hard sometimes rely on ‘getting’ the notes about texts, and thereby the ‘right’ answer, rather than developing the habits they need to be able to respond to any text, whether one they have encountered before or not. This is understandable: while English teachers will argue that all texts are ‘unseen’ before they are studied, pupils can become used to the scaffold of discussing with pairs or small groups, and the reassurance that, at the end, the teacher would eventually confirm the ‘right’ response by guiding the discussion and asking purposeful questions.

As Angela Duckworth says in Grit, ‘We prefer our excellence fully formed’ (2016). We would prefer to show the world the successful final outcome, rather than the training and experimenting, which means that committing pen to paper and articulating an interpretation of an unseen poem, or even just verbally expressing an idea in class discussion, could make unseen poetry a locus of fear and failure where pupils may feel intimidated by the myth that some people just ‘get it’ and others don’t, rather than seeing it as an enjoyable challenge. When I surveyed my Year 10 class about what they felt the biggest challenges in responding to unseen poetry were, several of their responses focused on the idea of a fixed, or correct interpretation – they were concerned about “analysing the text correctly” or finding “the right message/s of the poem”. While many of them commented that they liked “reading new poems” and to have a “fresh start and use things we’ve learnt from other poems”, it is interesting that the pressure to ‘get it right’ still prevails.

So I decided to give my pupils a challenge which would deliberately make them feel stuck. As a starter activity just as we started our unseen poetry unit, I gave them a poem which was on a Cambridge University end of year examination in 2014, and which consists only of punctuation[2]:

They were definitely daunted by this – in a survey after the lesson I asked them how they felt when they saw it:

- I felt a bit out of my depth, I struggled to analyse any of it

- Quite stuck for words… I wasn’t really sure where to start seeing as we had no context and there were no words so how were you able to deduce anything from it?

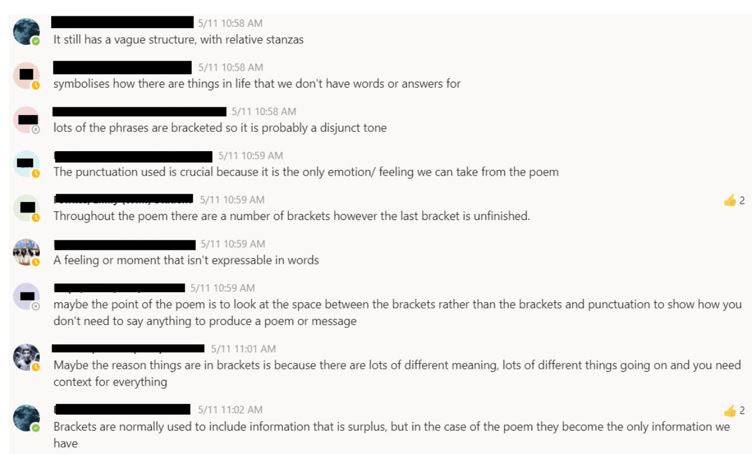

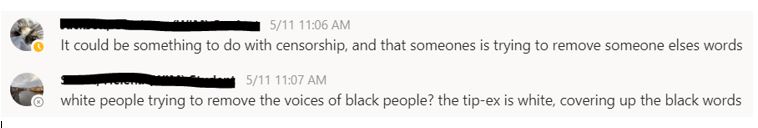

- Freaked out, how was I meant to be able to understand a poem with no words!These phrases echo exactly the sort of being ‘stuck’ feeling I’m sure we’ve all experienced when encountering something unfamiliar. The pupils spent some time on their own examining and annotating the poem, and then in a Teams video call we discussed the kinds of clues they could look for to help them understand the poem – although there weren’t words, they gradually began to use the information they did have, and came up with some insightful ideas, utilising the ideas about the structure and clues from the punctuation marks to try and gain some meaning from the poem. Here are some of the ideas from the Meeting Chat:

They were beginning to notice some really interesting ideas: the open-ended nature of the poem because of the unfinished last section, the implications of the punctuation marks which were there, and the fact that the lines were bracketed, suggesting some sort of devaluing of whatever words might have been inside them. I then revealed the title of the poem: ‘Tipp-Ex Sonata’, and explained that the poet, Koos Kombuis, was a South African performer and writer. With additional context, and using another pupil’s observation about apartheid, they then made some even more impressive deductions:

They had got very close to what Koos Kombuis had said about the poem himself: that it’s a protest against censorship of anti-apartheid voices in South Africa. So far, so good: the pupils had proved that they could reframe their thinking and use different clues to help them analyse the poem.

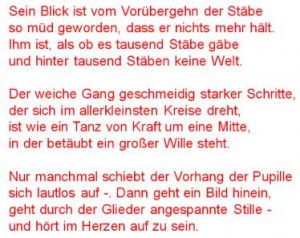

I then showed the pupils a poem in German:

This, naturally presented pupils with a different problem. However, they could identify rhyme and internal rhymes, alliteration and sound iconicity, and when they heard the poem aloud they could hear the regular, almost monotonous iambic pentameter. They identified that the first and last words of the poem were the same (although one is a pronoun and the other is a verb, they were using the right sort of reasoning!), and made an interesting point about the poem having a cyclical structure as a result. We spoke about how these gave the impression of something enclosed or making repeated movements – and of course, they were actually very close! This poem, ‘Der Panther’ by Rainer Maria Rilke[3], is about a panther, trapped in a cage and moving around in tiny circles as his mind calcifies. Without realising it, and without knowing any of the words, the pupils managed to understand this poem at a surprisingly deep level.

I then asked the pupils their feelings about unseen poetry, having attempted these two poems which would have been certainly at best uncomfortable, and at worst enough to make them feel ‘stuck’:

- I like analysing unconventional poems, because you can interpret it on a much broader range, rather than analysing the meaning of words and literary devices.

- less confused and a bit more confident in my capability to analysis texts

- it made me more confident in understanding different ways to analyse and use other methods to deduce a message from a poem

- Slightly reassured that annotations aren’t all there is to a poem and you can find other key elements elsewhere.

- After these activities, I feel like I have a better approach to unseen poetry, and am able to discover the writer’s meaning without context or the internet.

- now I understand that there is more than just the words on the page that can be understood.

- it makes it a lot clearer because I now know there are other ways to look at a poem, for example after looking at “der panther” it made me realise I could’ve looked at the rhyming structure or words that rhyme in order to get a sense of the poem.These pupils’ responses suggest that putting them out of their comfort zone and possibly dangerously close to their ‘panic zone’[4], actually made them understand that there were more tools available to them than the most obvious ones. (It is particularly gratifying to see that at least one has learnt they don’t need to consult Google!) Not only is unseen poetry now less daunting, because they had successfully engaged with something even more unfamiliar, but they had also deepened their understanding of a greater range of devices which poets use to create meaning.This is a really useful strategy for helping pupils engage with something which they might feel daunted by, especially when it’s a new topic. Another example is from a Year 13 lesson when we started Chaucer: I was concerned that my class would be daunted by Middle English when they encountered it for the first time, so gave them versions of a text in Old English dating from the 10th and 11th century, and then the same text in Middle English from the 14th century, at which point the pupils began to recognise trends and similarities in the language and structure, eventually identifying it as the Lord’s Prayer, before I provided a more familiar 16th century translation. Making these connections helped pupils feel less alienated by Middle English and more confident to approach Chaucer.

At WHS, we are fortunate enough to teach thoughtful, perceptive and independent students, and it’s encouraging to see the ways that they engage with really tricky material, and begin to see that, if they can tackle an undergraduate exam text in Year 10, they can tackle any poem! The same strategy could be used in many subjects – a piece of artwork which doesn’t look like what someone might assume to be ‘art’, a piece of music which challenges the expectations of a particular genre, data which might seem to buck a trend in science subjects. These lessons are memorable as well: one of the girls in my Year 13 class signed up for my elective module on Sociolinguistics on the strength of the introduction to Middle English activity which she had enjoyed several months earlier! By challenging pupils’ expectations and perceptions of their own limitations, they are able to see their subjects in a broader light than the examination syllabi, make connections with wider experiences, and learn a valuable lesson about what to do when they don’t know what to do.

References and Further Reading

Duckworth, A. (2016) Grit: Why passion and resilience are the secrets to success, Vermillion.

Dweck, C. (2006) Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Ballantine Books.

https://www.buildinglearningpower.com/2016/04/i-give-up/

https://www.buildinglearningpower.com/2016/05/getting-unstuck/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-27680904

http://www.thempra.org.uk/social-pedagogy/key-concepts-in-social-pedagogy/the-learning-zone-model/

[1] https://www.buildinglearningpower.com/2016/05/getting-unstuck/

[2] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-magazine-monitor-27680904

[3] https://www.poemhunter.com/poem/the-panther/

[4] http://www.thempra.org.uk/social-pedagogy/key-concepts-in-social-pedagogy/the-learning-zone-model/