Deputy Head Pastoral, Ben Turner, questions what role can schools play in tackling violence against women.

The killing of Sabina Nessa, a 28-year-old primary school teacher, has again brought the media spotlight onto how the government, and wider society, is protecting women and girls against violence. Six months on from Sarah Everard’s murder, questions are rightly being asked about whether women are any safer.

As we acknowledge the grief caused by the loss of another young woman, we must also look at our continued work to help safeguard young women in our own school community. While the spotlight has focussed on other areas, Wimbledon High has been busy outlining the pillars of the Wimbledon Charter. A set of principles around protecting young girls from sexual assault and harassment, as well as taking a proactive, preventative approach with both sexes in meaningful partnership with Kings College School, Wimbledon, and other prospective partners.

The Charter seeks to outline the key role every member of our and other school communities can play in safeguarding young people, as we seek lasting change in the way that girls and women are seen, recognising our role in wider society to protect and inform.

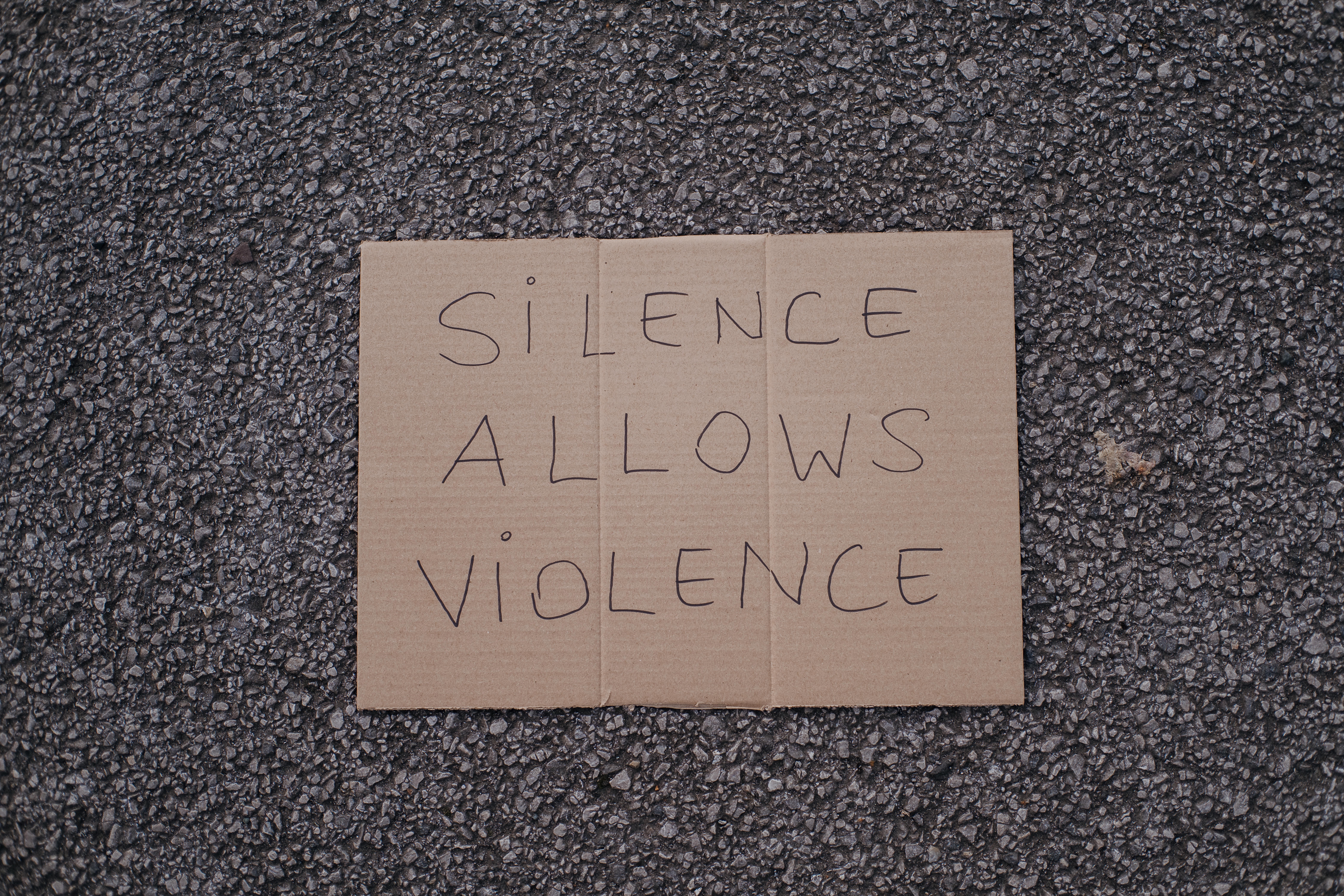

A safeguarding culture where voices are heard and protected

The Everyone’s Invited movement caused seismic shifts in the way that some institutions acted around reports of sexual assault and harassment. In our own school we have asked hard questions of how and when students are able to disclose what may have happened but also how those voices have been protected. Fundamental to the Charter is the acknowledgement that this is not solely a boys’ school issue. The importance of specialist training for staff, but also an acknowledgement and protection of peers, is essential in single and mixed sex institutions.

As a school we have taken some definitive steps to ensure we continue to reflect an open and overt safeguarding culture. The appointment of a Lead Counsellor, with a specialism in sexual trauma, has been an important step. Making that role clear to students and staff is equally important however and adding another ‘space’ that girls can go has been vital. Building on the safeguarding update that all staff receive, we will also seek to train at least four key pastoral staff as specialists in sexual violence and harassment in partnership with Lime Culture, which will be mirrored by KCS.

We must always ensure that we are working in partnership with those agencies that can affect change beyond the school gates. We are working closely with our Police Liaison, and other partners in Merton, to ensure that the sharing of information around risk and vulnerable students is always our first priority.

A proactive and synchronised programme of Relationship & Sex Education

The time for tea is over, was a line I wrote at the time of EI and the murder of Sarah Everard. I wrote it out of frustration with the manner in which PSHE can often be forgotten or diminished by teachers, and therefore schools, who are more focussed on the scholastic integrity of their subject than paying credence to a curriculum outside of their own department. Instead, schools have often deferred to experts, experts who come in for thirty or forty minutes, finishing with the notorious ‘cup of tea’ consent video, and ‘job done!’. The Charter is a call to arms for all teachers, to recommit to the knowledge that discussion of these topics, uncomfortable as they might be, is just as important, if not more so, than the discussion of an historical text or Maths equation. Moreover, it is so important that we have a candid conversation with ourselves, and our Year Teams, as to what topics we are comfortable teaching, and how we need to be supported in order to deliver the best RSE provision that our students deserve, and require.

Even more important is the knowledge that, through contextual safeguarding, we know that teens need to learn about relationships and sex earlier. It is too late to be addressing these issues at GCSE, when wider society and peer group are much more influential to teens than their parents or their school. ‘Age appropriate’ needs to be rethought, and our long-term partners in the RAP Project, and It Happens Education, are at the forefront of changing the landscape of conversations within schools. Together we want to tackle such topics as dating, partying, sexting, lad-culture & revenge porn. Teenagers are vulnerable to any number of these issues, and we seek to empower them with the law, the power of practicing discretion, mutual respect, and mutual consent.

This, however, is all very well if we are not ensuring that the same conversations are happing with boys of the same age. We are working with KCS, and other prospective partner schools, to ensure that we are following a programme that is synchronised across year groups, across schools, to ensure that teens are given the same information, earlier.

Meaningful and diverse partnership

There are two crucial partnerships that the Charter hopes to formalise. The first, recognises the vital role that parents play, individually and collectively, in supporting what is happening within schools. Parents face any number of individual challenges with their teenagers, and as they age, we know that school and home are far less influential than peers and wider society. Through parent consultation we know that there is a great deal that can be done by giving all parents a set of guidelines around parties, social time and curfews. We are believers in ‘elastic parenting’ and empowering teens to make decisions within clear boundaries. Parents, however, need the support of schools, and most importantly, each other, to ensure that they can put those boundaries in place, consistently.

The second partnership, and what I believe is the long-term key to our education’s role in preventing violence against women, is diverse and meaningful partnership between boys and girls. It is essential that men see women as more than mothers and potential girlfriends. Intellectual and social interaction, formalised across year groups is vital if we are to change endemic attitudes. That is why the Charter is committed to links like debating competitions for Year 10, leadership conferences for Sixth Formers, and transition activities with Year 7.

So, what next?

We hope to launch the Charter before Christmas and ensure that all steps have been taken, by both schools before launch. We hope that when the media spotlight once again leaves this issue, we will continue to be at the forefront of advocating for the safety and protection of women and girls, and the Charter seems like a meaningful platform to widen our fight.

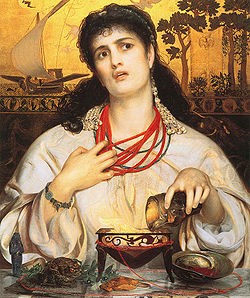

From Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) to Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1950), the presentation of women throughout literary history is fascinating, often providing a lens through which modern readers can appreciate the attitudes of the past. It is especially interesting to focus on the presentation of evil and transgressive women in literature, revealing the gender-based fears that have plagued western-society for almost two and a half millennia.

From Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) to Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1950), the presentation of women throughout literary history is fascinating, often providing a lens through which modern readers can appreciate the attitudes of the past. It is especially interesting to focus on the presentation of evil and transgressive women in literature, revealing the gender-based fears that have plagued western-society for almost two and a half millennia. These literary women also had in common their assertions of dominance over their husbands. Steinbeck claims that Cathy had “the most powerful impact upon Adam (her husband)” and Lady Macbeth was much the same, yielding a sinister amount of power over Macbeth. Medea emasculates Jason as she tells him his “complete lack of manliness” is “utterly vile”. This fear of female scorn is repeated in Macbeth as Lady Macbeth asserts “when you durst do it, then you are a man” in the face of her husbands hesitance to assassinate the king.

These literary women also had in common their assertions of dominance over their husbands. Steinbeck claims that Cathy had “the most powerful impact upon Adam (her husband)” and Lady Macbeth was much the same, yielding a sinister amount of power over Macbeth. Medea emasculates Jason as she tells him his “complete lack of manliness” is “utterly vile”. This fear of female scorn is repeated in Macbeth as Lady Macbeth asserts “when you durst do it, then you are a man” in the face of her husbands hesitance to assassinate the king. Often regarded as a cornerstone of ancient literary education, Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom a significant number of plays have survived. Aristotle described him as “the most tragic of poets” – he focused on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way that was previously unheard of. This was especially true in the sympathy he demonstrated to all victims of society, which included women. Euripides was undoubtedly the first playwright to place women at the centre of many of his works. However, there is much debate as to whether by doing this, Euripides can be considered to be a ‘prototype feminist’, or whether the portrayal of these women in the plays themselves undermines this completely.

Often regarded as a cornerstone of ancient literary education, Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom a significant number of plays have survived. Aristotle described him as “the most tragic of poets” – he focused on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way that was previously unheard of. This was especially true in the sympathy he demonstrated to all victims of society, which included women. Euripides was undoubtedly the first playwright to place women at the centre of many of his works. However, there is much debate as to whether by doing this, Euripides can be considered to be a ‘prototype feminist’, or whether the portrayal of these women in the plays themselves undermines this completely. Medea is undoubtedly a strong and powerful figure who refuses to conform to societal expectations, and through her Euripides to an extent sympathetically explores the disadvantages of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Because of this, the text has often been read as proto-feminist by modern readers. In contrast with this, Medea’s barbarian identity, and in particular her filicide, would have greatly antagonised a 5th Century Greek audience, and her savage behaviour caused many to see her as a villain.

Medea is undoubtedly a strong and powerful figure who refuses to conform to societal expectations, and through her Euripides to an extent sympathetically explores the disadvantages of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Because of this, the text has often been read as proto-feminist by modern readers. In contrast with this, Medea’s barbarian identity, and in particular her filicide, would have greatly antagonised a 5th Century Greek audience, and her savage behaviour caused many to see her as a villain. . Although this version is now lost, we know that he portrayed a shamelessly lustful Phaedra who directly propositioned Hippolytus on stage, which was strongly disliked by the Athenian audience. The surviving play, entitled simply ‘Hippolytus’, offers a much more even-handed and psychologically complex treatment of the characters: Phaedra admirably tries to quell her lust at all times. However, it could be argued that any pathos for her is lost when she unjustly condemns Hippolytus by leaving a suicide note stating that he raped her, which she does partly to preserve her own reputation, but also perhaps to take revenge for his earlier insults to her and her sex. It is debatable as to whether Euripides is trying to evoke sympathy for Phaedra and her unfortunate situation, or whether through her revenge she can ultimately be seen as a villain in the play.

. Although this version is now lost, we know that he portrayed a shamelessly lustful Phaedra who directly propositioned Hippolytus on stage, which was strongly disliked by the Athenian audience. The surviving play, entitled simply ‘Hippolytus’, offers a much more even-handed and psychologically complex treatment of the characters: Phaedra admirably tries to quell her lust at all times. However, it could be argued that any pathos for her is lost when she unjustly condemns Hippolytus by leaving a suicide note stating that he raped her, which she does partly to preserve her own reputation, but also perhaps to take revenge for his earlier insults to her and her sex. It is debatable as to whether Euripides is trying to evoke sympathy for Phaedra and her unfortunate situation, or whether through her revenge she can ultimately be seen as a villain in the play.