Written by: Emma Hamilton

Virgil’s epic, ‘The Aeneid’, tells the story of Aeneas; the dutiful Trojan hero who (after several sorrowful episodes) founds the city of Rome. It makes sense, therefore, that Virgil, writing under the first Roman emperor Augustus, creates links between the characters of his foundation myth and the powerful figures of ancient Rome which his readers inhabit. Often these links are quite clearly spelled out: readers can trace the bloodline from Aeneas right through to Julius Ceasar and Emperor Augustus, basking in the glory of Rome’s prestigious ancestry (Aeneas’ mother is a goddess). But I would like to highlight a less explicit but by no means less important comparison between Dido, the Queen of Carthage with whom Aeneas falls in love in Virgil’s poem, and Cleopatra, the last Egyptian Pharoah, and a crucial figure in the tumultuous final moments of the Roman Republic.

Firstly, arguably the most striking point of comparison between the two is that they are both women in positions of huge power and authority. This is rare in antiquity, as the power women obtained was ‘often obtained by the men they knew’ (kerriganfournier, 2020) and was exercised privately, such as Agrippina, Emperor Nero’s mother who applied her political influence under Nero’s official political office. However, this is not the case for Dido or for Cleopatra – they are powerful rulers in their own right. After her husband was murdered by her brother, Dido escaped across the Mediterranean to found a city of her own, where she was an active leader: ‘she was giving laws and rules of conduct to her people, and dividing the work that had to be done in equal parts’ (Virgil & West, 1991). Similarly, Cleopatra reigned over Egypt for 21 years, controlling the military, economy and society of this extremely powerful nation (not to mention keeping invading forces out). She was also a skilled linguist, speaking up to 7 languages (Plutarch & kerriganfournier, 2020) which was unusual, even for a Pharoah. Although these accomplishments are often hidden by the more dramatic elements of her story, it is important to acknowledge she was ruthless in her elimination of threats to her throne, with several siblings assassinated, but this was not unusual at this time – her own father killed off many of his rivals (including his children). As women in power were so uncommon in the ancient world, the comparison between Dido and Cleopatra here is important, as this power can be manipulated in retellings of their stories to explain their demises and act as an antithesis to the ‘untouchable’ power of Rome.

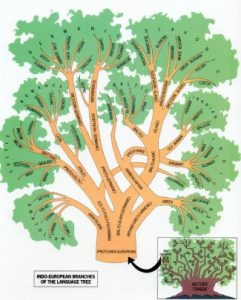

Another crucial aspect in these queens’ contrast to Rome is the fact they are foreign (to Rome). Foreigners had fewer rights than the average Roman citizen, and xenophobia was commonplace in Roman culture. Additionally, there is a ‘mystical’ element to foreign travellers/peoples in Roman literature. Necromancers (people who raised the deceased from the dead) were typically foreign characters, such as Zatchlas, an Egyptian prophet, from ‘sagae Thesselae’. These elements of distrust and disdain would have played a part in how Roman citizens viewed Cleopatra and Dido. So, why is this aspect of comparison important to Virgil? Because it allows him to emphasise the dutiful nature of Aeneas, the symbol of Roman glory, in contrast to the lovesick and non-Roman Queen. In a similar vein, Octavian’s (Emperor Augustus’ old name) triumph over Cleopatra and Mark Anthony becomes more than just a personal victory, but the victory of Rome over the ‘foreign threat’. In both cases, the power of Rome is emphasised, and the power of Cleopatra and Dido diminished.

I think it is also important to discuss their infamous deaths – so infamous that they have somewhat eclipsed their characters and accomplishments. Both die by suicide – a noble death in Roman times as it displayed a dedication to grief or to love. And yet, very few great male heroes of the classical world commit suicide – many die in battle, doing what they were most respected for. But in the case

of Dido and Cleopatra, they become remembered for the causes of their death: relationships with Roman (or Trojan) men, rather than their successes as rulers. They are remembered through their connection with Rome.

In my opinion, this final point summarises the most crucial comparison between Cleopatra and Dido: their stories are remembered in connection with Rome – how Rome defeated or abandoned them for the advancement of the empire. This is most likely because the stories were chiefly told by Romans. A large portion of our information about Cleopatra comes from Roman historian Plutarch’s biographies on Julius Caesar and Mark Anthony, and Dido’s story is only a short segment of Aeneas’ epic. Dido’s links with Cleopatra would reemphasise the power of Rome in Roman readers minds, and it could be argued this was intentional, acting as propaganda for Augustus, as he welcomed in a new age of Roman authority. It is a poignant reminder to be wary of historical sources, as the source will often tell you as much (or even more) about the writer as it does about the subject.

From Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) to Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1950), the presentation of women throughout literary history is fascinating, often providing a lens through which modern readers can appreciate the attitudes of the past. It is especially interesting to focus on the presentation of evil and transgressive women in literature, revealing the gender-based fears that have plagued western-society for almost two and a half millennia.

From Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) to Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1950), the presentation of women throughout literary history is fascinating, often providing a lens through which modern readers can appreciate the attitudes of the past. It is especially interesting to focus on the presentation of evil and transgressive women in literature, revealing the gender-based fears that have plagued western-society for almost two and a half millennia. These literary women also had in common their assertions of dominance over their husbands. Steinbeck claims that Cathy had “the most powerful impact upon Adam (her husband)” and Lady Macbeth was much the same, yielding a sinister amount of power over Macbeth. Medea emasculates Jason as she tells him his “complete lack of manliness” is “utterly vile”. This fear of female scorn is repeated in Macbeth as Lady Macbeth asserts “when you durst do it, then you are a man” in the face of her husbands hesitance to assassinate the king.

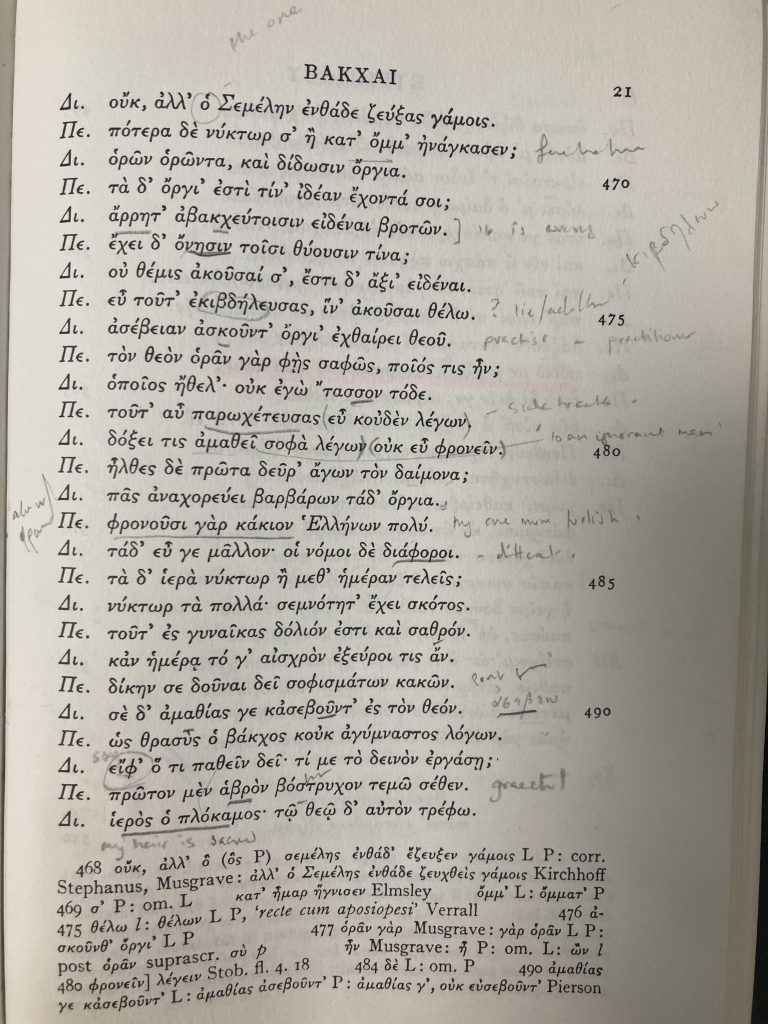

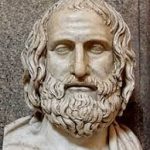

These literary women also had in common their assertions of dominance over their husbands. Steinbeck claims that Cathy had “the most powerful impact upon Adam (her husband)” and Lady Macbeth was much the same, yielding a sinister amount of power over Macbeth. Medea emasculates Jason as she tells him his “complete lack of manliness” is “utterly vile”. This fear of female scorn is repeated in Macbeth as Lady Macbeth asserts “when you durst do it, then you are a man” in the face of her husbands hesitance to assassinate the king. Often regarded as a cornerstone of ancient literary education, Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom a significant number of plays have survived. Aristotle described him as “the most tragic of poets” – he focused on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way that was previously unheard of. This was especially true in the sympathy he demonstrated to all victims of society, which included women. Euripides was undoubtedly the first playwright to place women at the centre of many of his works. However, there is much debate as to whether by doing this, Euripides can be considered to be a ‘prototype feminist’, or whether the portrayal of these women in the plays themselves undermines this completely.

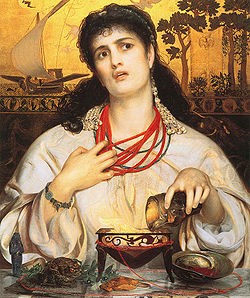

Often regarded as a cornerstone of ancient literary education, Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom a significant number of plays have survived. Aristotle described him as “the most tragic of poets” – he focused on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way that was previously unheard of. This was especially true in the sympathy he demonstrated to all victims of society, which included women. Euripides was undoubtedly the first playwright to place women at the centre of many of his works. However, there is much debate as to whether by doing this, Euripides can be considered to be a ‘prototype feminist’, or whether the portrayal of these women in the plays themselves undermines this completely. Medea is undoubtedly a strong and powerful figure who refuses to conform to societal expectations, and through her Euripides to an extent sympathetically explores the disadvantages of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Because of this, the text has often been read as proto-feminist by modern readers. In contrast with this, Medea’s barbarian identity, and in particular her filicide, would have greatly antagonised a 5th Century Greek audience, and her savage behaviour caused many to see her as a villain.

Medea is undoubtedly a strong and powerful figure who refuses to conform to societal expectations, and through her Euripides to an extent sympathetically explores the disadvantages of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Because of this, the text has often been read as proto-feminist by modern readers. In contrast with this, Medea’s barbarian identity, and in particular her filicide, would have greatly antagonised a 5th Century Greek audience, and her savage behaviour caused many to see her as a villain. . Although this version is now lost, we know that he portrayed a shamelessly lustful Phaedra who directly propositioned Hippolytus on stage, which was strongly disliked by the Athenian audience. The surviving play, entitled simply ‘Hippolytus’, offers a much more even-handed and psychologically complex treatment of the characters: Phaedra admirably tries to quell her lust at all times. However, it could be argued that any pathos for her is lost when she unjustly condemns Hippolytus by leaving a suicide note stating that he raped her, which she does partly to preserve her own reputation, but also perhaps to take revenge for his earlier insults to her and her sex. It is debatable as to whether Euripides is trying to evoke sympathy for Phaedra and her unfortunate situation, or whether through her revenge she can ultimately be seen as a villain in the play.

. Although this version is now lost, we know that he portrayed a shamelessly lustful Phaedra who directly propositioned Hippolytus on stage, which was strongly disliked by the Athenian audience. The surviving play, entitled simply ‘Hippolytus’, offers a much more even-handed and psychologically complex treatment of the characters: Phaedra admirably tries to quell her lust at all times. However, it could be argued that any pathos for her is lost when she unjustly condemns Hippolytus by leaving a suicide note stating that he raped her, which she does partly to preserve her own reputation, but also perhaps to take revenge for his earlier insults to her and her sex. It is debatable as to whether Euripides is trying to evoke sympathy for Phaedra and her unfortunate situation, or whether through her revenge she can ultimately be seen as a villain in the play.