Agnes P. in Year 9 takes us on a lively whistle-stop tour of key features and sights in the history of Classical Western Architecture, looking at the three main styles – Ancient Greek, Roman and Byzantine – that underpin the architecture we see around us today

Architecture governs our lives. We live in a metropolis and everywhere we turn there is a new street with buildings from a variety of eras that give us the ability to eat, sleep and to live. In the Palaeolithic period, roughly 2.5 million years ago, when humans lived in huts and hunted wildlife for food, the key purpose of architecture was to provide shelter, but now, we have many uses for it, due to the wealth, wisdom and resources amassed by humanity over 2.5 million years. But we can still trace the roots of much modern architecture back to ancient times.

Archaic architecture from as early as the 6th century BC has influenced many architects over the past two millennia. If you have ever been to the British Museum, a building designed to mimic the Greek style, and looked up at the columns just before the entrance, you will have noticed the ornate capitals, decorated with scrolls and Acanthus leaves. They are derived from the two principal orders in Archaic architecture: Doric and Ionic. The Doric order occurred more often on the Greek mainland where Greek colonies were founded. The Ionic order was more common among Greeks in Asia Minor and the Islands of Greece. These orders were crucial if you were an architect living in 600 BC. Temples were buildings that defined Greek architecture. They were oblong with rows of columns along all sides. The pediment (the triangular bit at the top) often showed friezes of famous scenes in the bible or victories achieved by the Greeks. The wealth that was accumulated by Athens after the Persian Wars enabled extensive building programs. The Parthenon in Athens shows the balance of symmetry, harmony, and culture within Greek architecture; it was the centre of religious life and was built especially for the Gods to show the strength in their beliefs. Greek architecture is very logical and organised. Many basic theories were founded by Greeks and they were able to develop interesting supportive structures. They also had a good grasp of the importance of foundation and were able to use physics to build stable housing.

The Romans were innovators. They developed new construction techniques and materials with complex and creative designs. They were skilled mathematicians, designers and rulers who continued the legacy left by Greek architects. Or as the Greeks might put it: pretentious copycats who stole their ideas and claimed them as their own. We sometimes forget that the origins of Roman Architecture lay within Greek history. Nonetheless, brand new architectural structures were produced, such as the triumphal arch, the aqueduct, and the amphitheatre. The Pantheon is the best-preserved building from Ancient Rome, with a magnificent concrete dome. The purpose of the pantheon is unclear but the decoration on the pediment shows that it must have been a temple. Like many monuments, it has a chequered past. In 1207 a bell tower was added to the porch roof and then removed. In the Middle Ages, the left side of the porch was damaged and three columns were replaced. But despite further changes, the Pantheon still remains one of the most famous buildings and the best preserved ancient monument in the world. It even contains the tombs of the Italian monarchy and the tomb of Raphael, an Italian renaissance painter. Roman architecture is known for being flamboyant, and many features reflect the great pride of this culture, such as the great pediments, columns, and statues of Romans doing impressive things. These all show off their understanding of mathematics, physics, art, and architecture. Many American designs have been inspired by this legacy, including the White House and the Jefferson Memorial, which couldn’t look more Roman if it tried.

Byzantine architecture was the style that emerged in Constantinople. Buildings included soaring spaces, marble columns and inlay, mosaics, and gold-coffered ceilings. The architecture spread from Constantinople throughout the Christian East and in Russia. Hagia Sophia is a basilica with a 32-metre main dome, dedicated to the Holy Wisdom of God. The original church was built during the reign of Constantine I in 325 AD. His son then consecrated it in 360 AD and it was damaged by a fire during a riot in 404 AD. In 558 AD an earthquake nearly destroyed the entire dome and so it was rebuilt on a smaller scale. It was looted in 1204 by the Venetians and the Crusaders until after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453. Mehmed II converted it into a mosque but in 1935 it was made a museum. But then it was converted back into a mosque in 2020. The history of the Pantheon looks paltry compared to the history of Hagia Sophia!

Byzantine architecture remains as a reminder of the spiritual and cultural life of people who lived in the Byzantine era. The use of mosaic during the Byzantine era has inspired modern architects to create themed works using gold mosaic to evoke beauty, religiosity, and purity.

Sources:

Encyclopædia Britannica

The London Library

MetMuseum – The Metropolitan Museum of Art Website

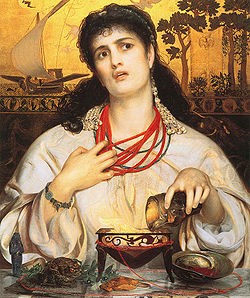

From Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) to Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1950), the presentation of women throughout literary history is fascinating, often providing a lens through which modern readers can appreciate the attitudes of the past. It is especially interesting to focus on the presentation of evil and transgressive women in literature, revealing the gender-based fears that have plagued western-society for almost two and a half millennia.

From Euripides’ Medea (431 BC) to Steinbeck’s East of Eden (1950), the presentation of women throughout literary history is fascinating, often providing a lens through which modern readers can appreciate the attitudes of the past. It is especially interesting to focus on the presentation of evil and transgressive women in literature, revealing the gender-based fears that have plagued western-society for almost two and a half millennia. These literary women also had in common their assertions of dominance over their husbands. Steinbeck claims that Cathy had “the most powerful impact upon Adam (her husband)” and Lady Macbeth was much the same, yielding a sinister amount of power over Macbeth. Medea emasculates Jason as she tells him his “complete lack of manliness” is “utterly vile”. This fear of female scorn is repeated in Macbeth as Lady Macbeth asserts “when you durst do it, then you are a man” in the face of her husbands hesitance to assassinate the king.

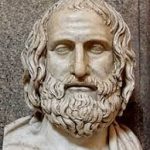

These literary women also had in common their assertions of dominance over their husbands. Steinbeck claims that Cathy had “the most powerful impact upon Adam (her husband)” and Lady Macbeth was much the same, yielding a sinister amount of power over Macbeth. Medea emasculates Jason as she tells him his “complete lack of manliness” is “utterly vile”. This fear of female scorn is repeated in Macbeth as Lady Macbeth asserts “when you durst do it, then you are a man” in the face of her husbands hesitance to assassinate the king. Often regarded as a cornerstone of ancient literary education, Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom a significant number of plays have survived. Aristotle described him as “the most tragic of poets” – he focused on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way that was previously unheard of. This was especially true in the sympathy he demonstrated to all victims of society, which included women. Euripides was undoubtedly the first playwright to place women at the centre of many of his works. However, there is much debate as to whether by doing this, Euripides can be considered to be a ‘prototype feminist’, or whether the portrayal of these women in the plays themselves undermines this completely.

Often regarded as a cornerstone of ancient literary education, Euripides was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom a significant number of plays have survived. Aristotle described him as “the most tragic of poets” – he focused on the inner lives and motives of his characters in a way that was previously unheard of. This was especially true in the sympathy he demonstrated to all victims of society, which included women. Euripides was undoubtedly the first playwright to place women at the centre of many of his works. However, there is much debate as to whether by doing this, Euripides can be considered to be a ‘prototype feminist’, or whether the portrayal of these women in the plays themselves undermines this completely. Medea is undoubtedly a strong and powerful figure who refuses to conform to societal expectations, and through her Euripides to an extent sympathetically explores the disadvantages of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Because of this, the text has often been read as proto-feminist by modern readers. In contrast with this, Medea’s barbarian identity, and in particular her filicide, would have greatly antagonised a 5th Century Greek audience, and her savage behaviour caused many to see her as a villain.

Medea is undoubtedly a strong and powerful figure who refuses to conform to societal expectations, and through her Euripides to an extent sympathetically explores the disadvantages of being a woman in a patriarchal society. Because of this, the text has often been read as proto-feminist by modern readers. In contrast with this, Medea’s barbarian identity, and in particular her filicide, would have greatly antagonised a 5th Century Greek audience, and her savage behaviour caused many to see her as a villain. . Although this version is now lost, we know that he portrayed a shamelessly lustful Phaedra who directly propositioned Hippolytus on stage, which was strongly disliked by the Athenian audience. The surviving play, entitled simply ‘Hippolytus’, offers a much more even-handed and psychologically complex treatment of the characters: Phaedra admirably tries to quell her lust at all times. However, it could be argued that any pathos for her is lost when she unjustly condemns Hippolytus by leaving a suicide note stating that he raped her, which she does partly to preserve her own reputation, but also perhaps to take revenge for his earlier insults to her and her sex. It is debatable as to whether Euripides is trying to evoke sympathy for Phaedra and her unfortunate situation, or whether through her revenge she can ultimately be seen as a villain in the play.

. Although this version is now lost, we know that he portrayed a shamelessly lustful Phaedra who directly propositioned Hippolytus on stage, which was strongly disliked by the Athenian audience. The surviving play, entitled simply ‘Hippolytus’, offers a much more even-handed and psychologically complex treatment of the characters: Phaedra admirably tries to quell her lust at all times. However, it could be argued that any pathos for her is lost when she unjustly condemns Hippolytus by leaving a suicide note stating that he raped her, which she does partly to preserve her own reputation, but also perhaps to take revenge for his earlier insults to her and her sex. It is debatable as to whether Euripides is trying to evoke sympathy for Phaedra and her unfortunate situation, or whether through her revenge she can ultimately be seen as a villain in the play.