Verity in Year 12 looks at how the pre-Raphaelites interpreted the tales of King Arthur and his court for a nineteenth century audience, emphasising their splendour as well as the challenge they could express to Victorian materialism and industrialisation

The tales of King Arthur and his knights have been popular for hundreds of years and have been reworked and re-interpreted by different groups and cultures. Thought to have originated in Celtic, Welsh, and Irish legends, the figure of Arthur appears as either a great warrior defending Britain from both human and supernatural enemies, or as a magical figure of folklore.

Though the tales were drawn from different sources – many of the most famous coming from French writers such as Chretien de Troyes – the story’s international popularity largely came from Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the King of Britain), Thomas Malory’s Morte d’Arthur and most importantly Lord Alfred Tennyson’s poems. These works inspired the second phase in Pre-Raphaelitism. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was a group of men (and a few important women) in the 1850s who challenged the artistic conventions of genre painting to instead ‘go to nature’ and work with the idea of realism.

Their principal themes were initially religious, but they also used subjects from literature and poetry, particularly those dealing with love and death. King Arthur’s knights of the Round Table presented the idea of an all-male community collectively devoted to a reforming project, and the brotherhood’s collaborative working patterns also reflected that.

The Arthurian Tales do not focus on one particular person, genre or event but they encompass numerous people and places – from the Guinevere and Lancelot scandal to Sir Gawain and his encounter with the mystical Green Knight; the sorceress Morgan Le Fay and Nimue; Arthur’s wizard advisor, Merlin, to Arthur’s son, Mordred, who brought about the legendary king’s ultimate downfall. Some of the most well-known paintings of the movement were the paintings depicting the The Lady of Shalott by William Waterhouse.

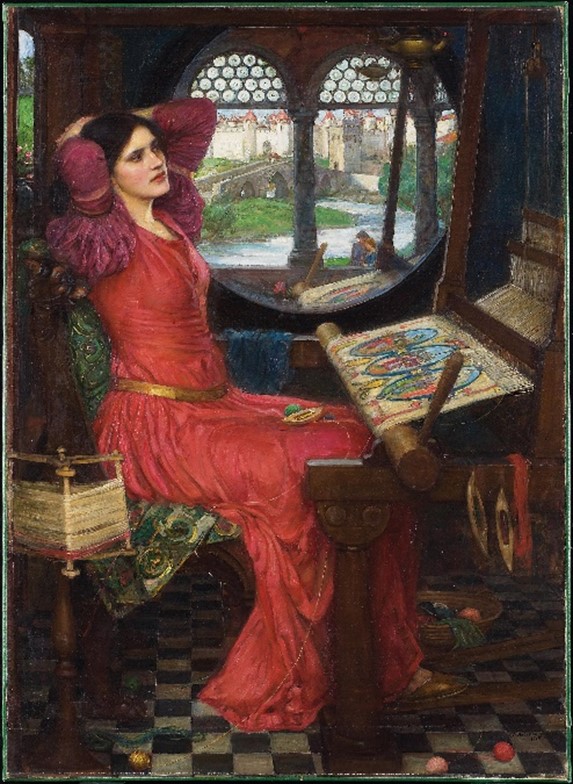

I am Half Sick of Shadows, The Lady of Shalott looking at Lancelot and The Lady of Shalott – William Waterhouse

These paintings tell the story of a woman who is forbidden to leave her tower and who can only see the outside world through a mirror, otherwise she will suffer a curse. The first part of the poem was depicted in the 1915 painting I am Half-Sick of Shadows Said the Lady of Shalott. The lady, trapped in her tower, spends her days weaving the images she sees in the mirror and at the moment captured in the painting, there are two lovers.

When the moon was overhead,

Came two young lovers lately wed,

‘I am half sick of Shadows’,

Said the Lady of Shalott.

In the painting there is a poppy in the reflection of the mirror but not in the foreground which foreshadows the lady’s death since poppies symbolise eternal sleep. Also, the weaving shuttles are shaped like boats which predict the final part of the poem. The next part was shown in the 1894 painting The Lady of Shalott Looking at Lancelot. The Lady sees Sir Lancelot in her mirror and falls instantly in love. She turns to properly look at him and the mirror shatters fulfilling the curse.

Out flew the web and floated wide;

The mirror crack’ d from side to side;

‘The curse come upon me,’

Cried the Lady of Shalott.

The lady is painted looking directly at the viewer with a defiant stare. She is tangled in the threads of her tapestries holding a small wooden shuttle, preparing to flee in order to find Lancelot. Within the context of 19th century Britain, Waterhouse may have implied that she is a woman of agency, defying her confinement and going after what she desires most. One could also say that Tennyson’s poem captured many artists’ ideas, especially the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, about whether they should capture nature truthfully or give their own interpretation. The Lady’s actions could reflect an artist breaking away from imagination and seeing the world in real life.

The final instalment of the poem is captured in The Lady of Shalott painted first in 1888. The lady moves downstream in a boat inscribed with her name on the prow holding the chains that tether her. On the boat is a crucifix symbolizing sacrifice and three candles, two of which have been blown out suggesting that her death will come soon. The woman’s lips are parted showing how she is singing her final song before her death.

For ere she reach’d upon the tide,

The first house by the water-side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott.

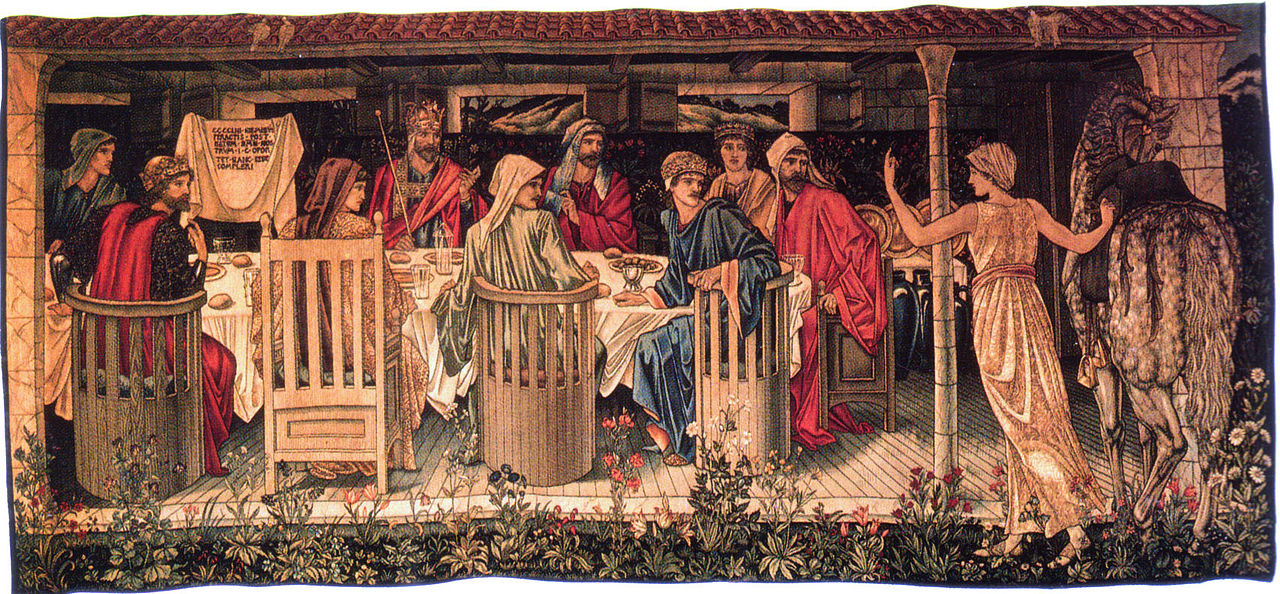

The Beguiling of Merlin – Edward Burne-Jones

Another favourite is The Beguiling of Merlin painted in 1872 by Edward Burne-Jones. It shows a snake-crowned Nimue enchanting Merlin with his own sorcery by binding him into a tree in the forest. Merlin’s helplessness and entrapment is conveyed by the serpentine lines of the drapery and tree branches that imprison the wizard and deprive him of his power. This fluidity of line also captures the ebb and flow of magic. Furthermore, his droopy hands and glass-eyed demeanour reinforce the sense of paralysis. Like a lot of his work, Burne-Jones explores power relationships in which a man falls victim to a hidden threatening female power.

Guenevere – William Morris

The character of Guinevere and the scandal with Lancelot is also repeatedly depicted. Guinevere is the legendary Queen and wife of King Arthur and in French romantic interpretations she has a love affair with her husband’s chief knight and friend, Lancelot. William Morris’s painting Guenevere or La Belle Iseult is a portrait of the model and wife of Morris, Jane Burden in medieval dress. She was discovered by Morris and Rossetti when they were working together on the Oxford murals and she later became a model for several different artworks like Rossetti’s Proserpine, Sir Launcelot in the Queen’s Chamber and more of Morris’s work.

In both Morris’ and Rossetti’s paintings Burden is cast not only as a queen but as an adulteress. The way life later imitated art has an uncanny force, particularly considering Burden later became the lover of Rossetti in the 1860s. The rich colours, the emphasis on pattern and details such as the missal reveal where Morris’s true talents lay. He was less at home with figure painting than with illumination, embroidery, and woodcarving, and he struggled for months on this picture. Most people will know him as a key figure in the Arts & Crafts Movement having probably seen his wallpapers and designs.

The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon – Edward Burne-Jones

Six and a half metres wide The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon marked the culmination of Burne-Jones’ fascination with Arthurian legend. The painting, which took 17 years and remained unfinished, depicts a moment of rest and inaction. Mortally wounded, King Arthur rests his head on the lap of his sister, the fairy queen Morgana, who took her brother to Avalon after his defeat in battle. At the centre of the Arthurian tales is the idea that he did not actually die, but sleeps in Avalon, waiting for the moment when the nation will most need his return.

From its earliest roots the story of King Arthur has been changing hands and remoulded to fit the cultures and society of the time. For the Pre-Raphaelites and the Victorian era, the legend resonated with them. In part they found splendour in it – sparkling armour and swords, flying banners and beautiful maidens in flowing robes. On the other hand, Arthur became a symbol of their crusade against the mundane and the crude materialistic era that was Victorian industrialisation. They reshaped Arthur to become a means to convey the morals and the monarchical society of the time.

Edward Burne-Jones – Alison Smith

The Art of the Pre-Raphaelites – Elizabeth Prettejohn

https://owlcation.com/humanities/arthurianlegendthroughouttheages

https://owlcation.com/humanities/The-Evolution-of-King-Arthur