Suzanne Stone, French teacher at WHS, considers the importance of listening in the language classroom and asks how we can make pupils more confident, and ultimately better, listeners.

Who hasn’t experienced first-hand, in the good old days of international travel, the frustration of not being able to understand the language we can hear around us; where seemingly basic, everyday interactions can sound like a fast stream of unintelligible phrases that can leave us feeling all at sea?

Within a school setting, the classroom can evoke similar frustrations as students try to make sense of the language spoken by their teacher or heard through audio files. Consequently, groans, sighs and puzzled brows are not an uncommon sight for MFL teachers at the front of the room, nor are comments such as ‘Why is listening so hard?’ particularly when progressing from KS3 to GCSE, and then on through to A Level.

It comes as little surprise, therefore, that several studies have documented that students can approach listening tasks with a sense of anxiety (Graham 2017). Indeed for some, it can be the skill that is enjoyed the least and feared the most. Some students see listening tasks as a test or measure against which they assess their understanding and ability. A more challenging exercise can dent existing confidence, or ‘self-efficacy’ (Graham 2007), in other words the feeling that you are good at something, so undermining motivation and possibly the desire to continue with that subject later on.

So, why can listening in the classroom conjure up anxieties such as this?

‘Our brain needs to perform in real time in order to extract meaning from any utterance we hear’ (Conti and Smith 2019)

It goes without saying that listening to an audio file on OneNote is not exactly the same as listening to a real-life person who is looking at you, whose interactions, intonations and gestures can help you decipher mood and meaning. When listening, we are making many demands on our memory. We have to master holding on to all the incoming information at varying speeds whilst being able to ‘sift’ this information as we hear it, breaking it down into its component parts of words, phrases and grammar. All these processes present a challenge, particularly as any new information can often erase the previous one, especially in time-pressurised situations (Field 2008).

So, why does it matter?

‘Nature gave us one tongue and two ears so we could hear twice as much as we speak’

Epictetus, Greek Stoic philosopher

Surely listening is just one of many skills involved in learning a language? I would argue that it is the most important skill, as it is the precursor to speaking and inextricably linked to responding. How can you ever hope to master speaking if you are a poor listener?

Listening is not the ‘passive’ skill it was once said to be. We acquire our first language through listening to several thousand hours of being spoken to before we begin to speak intelligibly, so our brains are hard-wired to work out meaning from what we hear around us (Graham et al 2010). Julian Walker (2021), a linguistic historian, describes the ‘Tommy French’ that arose from the interactions of English-speaking troops with civilians during WW1. Their experience in France during the war led to the special language they invented in order to cope with their situation. ‘San fairy ann’, ‘toot sweet’ are anglicized French phrases (Ça ne fait rien, tout de suite) that came into use on the Western Front during the First World War as British troops struggled to communicate in French. Fortunately for us, we have a greater understanding in education of the processes of how we listen and have moved away from this rather limiting, sink or swim approach.

How can we help students become better listeners?

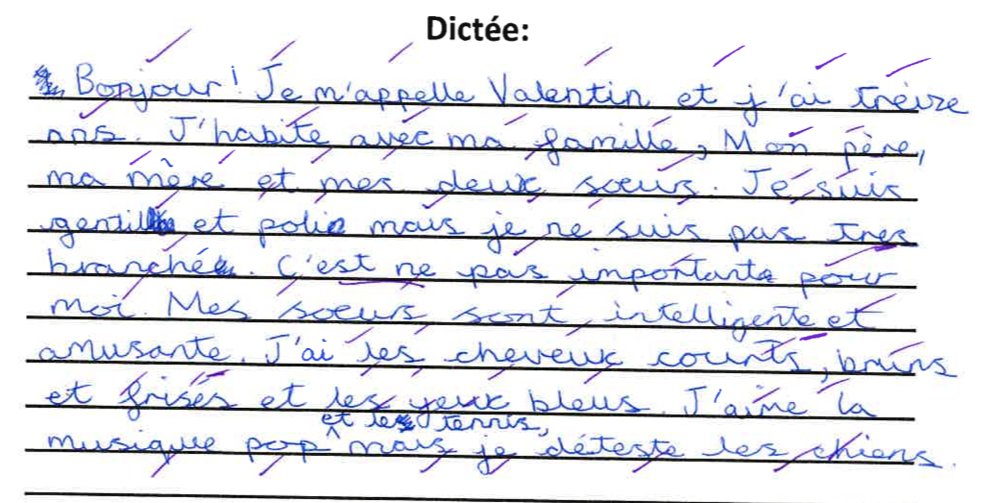

In learning a language, we can develop our students’ ability to listen. We can reduce anxiety and build confidence by incorporating strategies in our MFL teaching which hone the skills needed to process and respond to information we hear. It is not only the exercises we use in lessons such as dictation, dictagloss, gap-fills and games that make listening fun, but it is also the work on phonics, reading aloud and oral practice in our classroom interactions which, in turn, enable students to become better listeners.

Dictationsimprove our ability to respond to what we hear, so helping us become more authentic speakers of the language too.

How can students improve their MFL listening skills?

- Try different approaches

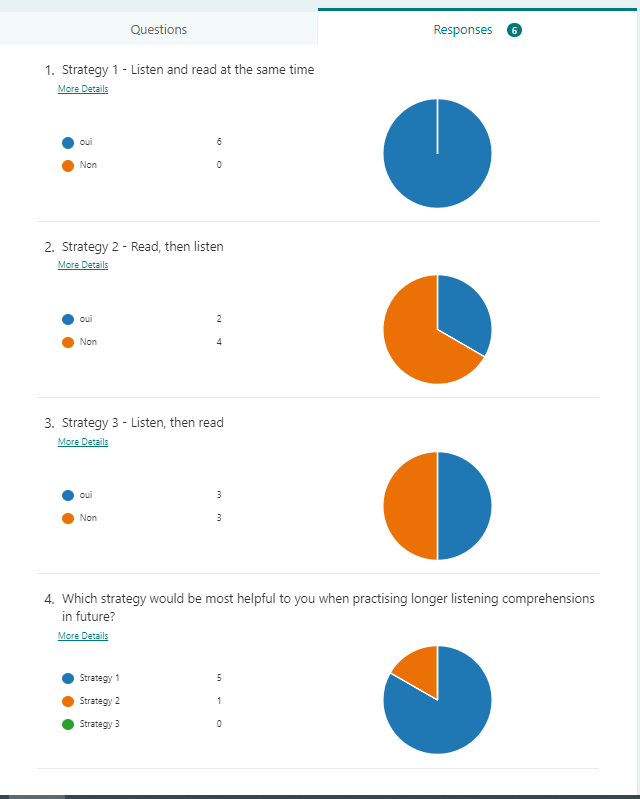

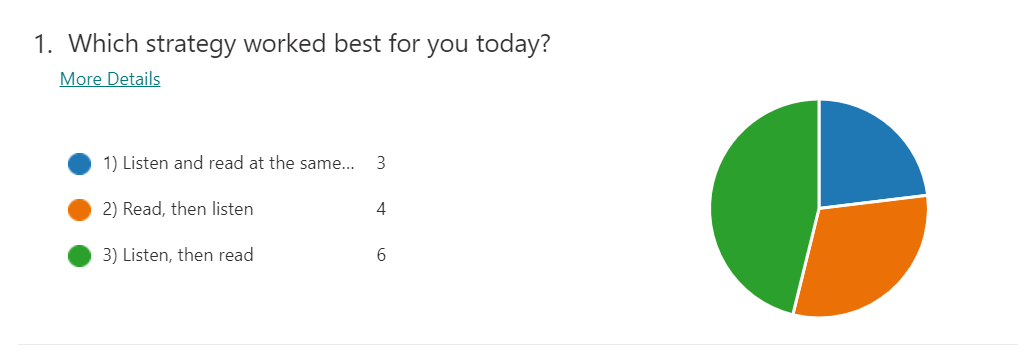

Some of our Year 11 and Year 12 French students have been trying out different listening strategies to gain an understanding of different ways to cope with harder texts.

Sharing our thinking and working through strategies together in this way will hopefully promote independence and confidence and reduce anxiety in the process.

- Build up your vocabulary!

Having a broad vocabulary is key to learning and understanding another language. Try making Quizlet flashcards and use the audio file to practise pronunciation. Alternatively, listen to a podcast such as Coffee break French, or a foreign language film or series with the subtitles in French or in English – Lupin on Netflix is a popular choice here!

Final thoughts

Know how to listen, and you will profit even from those who talk badly.

Plutarch, Greek biographer

So, how can we become better listeners? As discussed in a previous blog by our Director of Sport, in mastering a skill, repetition is crucial and listening is no different. In short, you get better at what you practise and by improving our listening, we can hope to become better speakers too.

Sources and further reading:

Gianfranco Conti and Steve Smith, Breaking the sound barrier: teaching learners how to listen, 2019

Steve Smith – A process approach to listening – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tQhh6b6BTJI&list=PL_FfkTb7PcMG7V_KE-N9r9NMmB1-GrF0c

John Field, Listening in the Language Classroom, 2009

Julian Walker, Tommy French: How British First World War Soldiers Turned French into Slang, 2021

Graham S, Learner strategies and self-efficacy: making the connection, 2007

Graham S, Research into practice: listening strategies in an instructed classroom setting, 2017

Graham S, Santos, D, & Vanderplank, R, Strategy clusters and sources of knowledge in French L2 listening comprehension, 2010

Coffee Break French https://coffeebreaklanguages.com/category/coffee-break-french/