Miss Emily Anderson, Head of History at WHS, evaluates the progress of the diversity in the curriculum working party since September, and reflects on our next steps.

It has been both a challenge and a privilege to have been leading the working party examining diversity in the curriculum since the Autumn Term. Ensuring that our curriculum is fit for purpose in both empowering our students to be active citizens of the world in which they live, and reflecting both their identities and those they will live and work alongside in their local, national and global communities could not be a more vital part of our work as teachers, individually, in departments and as part of the whole school. Such a curriculum would simultaneously support our students and ensure they feel that they belong in the WHS community, and would empower them to understand and champion diversity in their lives beyond school. The curriculum is not a fixed entity, and the constant re-evaluation of it is one of, to my mind, the most challenging and important parts of our professional lives as teachers.

As members of the school community will be aware from his letters and assemblies, in the autumn Deputy Head Pastoral Ben Turner asked staff, as part of our commitment to systemic change, to scrutinise three different areas of our work as a school in order to better inform our future direction. Alongside our scrutiny of the curriculum, colleagues have been looking at our recruitment of students and staff and how we reach out to a broader and more diverse range of communities, and at our work with our students beyond the curriculum, in our pastoral, super-curricular and extra-curricular contexts.

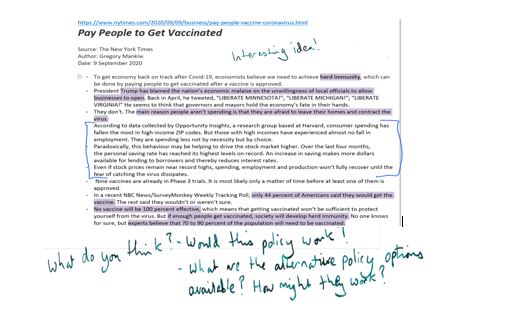

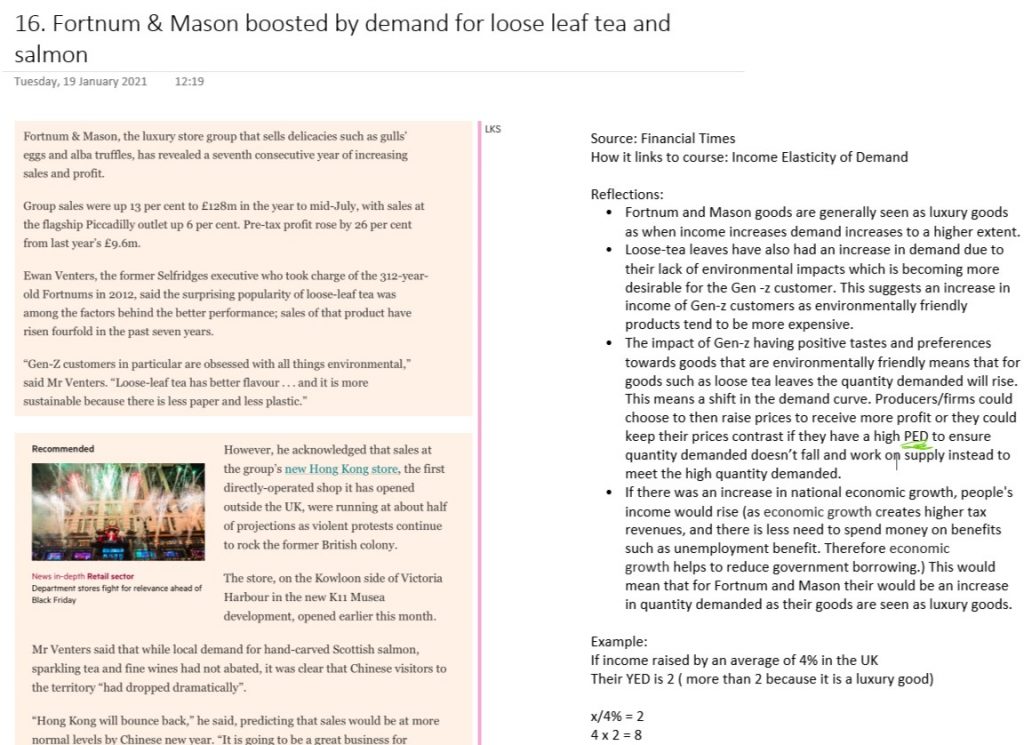

Examining the curriculum were staff from the arts, sciences and humanities, bringing a variety of perspectives. I wanted to make an ambitious but absolutely necessary distinction from the outset – that we cannot approach the curriculum by diversifying what is already there, but need to create a curriculum that is inherently diverse. We discussed the need to broaden our collective understanding of different identities (the GDST’s Undivided work has been very valuable in this regard), and to model open, honest and often difficult dialogue. The difficulties of the process of change were also considered, especially the transition from an old to a new curriculum, and the fear of being labelled knee-jerk or tokenistic until it became embedded and normal. This is, however, no excuse for not trying. Doing nothing is not an option. Three areas for evaluation emerged for us to take to departments:

- The day-to day – teachers’ understanding about different types of diversity, our use of language and resources in the classroom, encouraging more challenging and reflective discussions in the classroom.

- The medium term – creating a diverse curriculum at WHS – looking again at KS3, and evaluating our choices at KS4 and KS5 to identify more diverse lines of enquiry or exemplars in existing specifications, or opportunities to move to other boards.

- The bigger picture – joining the growing national conversation with exam boards to make changes to GCSEs and A Levels to better reflect diverse identities, critically evaluating the cultural assumptions and frameworks through which our knowledge is formed and which privilege certain identities over others, to problematise and ultimately change these in our teaching.

The reflections that came back from discussions at department level showed that much carefully considered planning is being undertaken across departments, in terms of the individuals whose voices are heard through study of their work, the enquiries that are planned to broaden our students’ horizons and the pedagogical implications of how we create an environment in which diverse identities can be recognised and understood.

My own department (History) are completely reconceiving our curriculum. My colleague, Holly Beckwith, wrote a beautiful rationale for this in WimTeach last year which I would highly recommend reading.[1] We have been preparing for major curriculum change for a number of years, firstly through trialling experimental enquiries to pave the way, such as a new Y9 enquiry on different experiences of the First World War. Our choosing of a unit on the British Empire c1857-1967 at A Level – a unit whose framework could, if taught uncritically, be problematic in terms of what it privileges, but which enables us to at least explore, understand and challenge such power structures and give voice to some of the people it oppressed through the study of historical scholarship – also helps facilitate changes further down the school as it demands significant contextual knowledge about societies across the world before the age of European imperialism.[2] Now, we are in a position to put in place major and increasingly urgently needed changes for September 2021 at Year 7 and Year 10, which will lead to a transformed KS3 and KS4 curriculum over the next three years.

To pivot back to the whole-school context, I also met with student leaders from each year group who had collated ideas from their peers to feed back. These were wonderfully articulately and thoughtfully put, often critical, and unsurprisingly revealed a great appetite for change. As teachers and curriculum designers, there is a balance to be struck here between taking students’ views into account, and creating coherent and robust curricula where knowledge and conceptual thinking builds carefully as students progress up the school – areas of study cannot simply be swapped in and out. As I have alluded to above, for example we start sowing the seeds of contextual understanding for GCSE and A Level at Y7. Furthermore, this process will take time, as meaningful change always does, and so managing expectations is also something we must consider. In and of itself, modelling the process of systemic change is such a valuable lesson for our students so this must be seen as an opportunity to demonstrate this.

So far, this process of evaluation has prompted profound and necessary reflection by teachers not only on what we teach in the classroom, but on how our own understandings of our disciplines have been conditioned by our experiences and educations. As well as educating our students, we are also continually educating ourselves, often unlearning old ideas. There is still a significant way to go in creating the inherently diverse curriculum we are aiming for, and I look forward to continuing to challenge and be challenged as we work together as a community to, ultimately, try to do right by our students and our world.

References:

[1] http://whs-blogs.co.uk/teaching/vaulting-mere-blue-air-separates-us-history-connection/

[2] Akala, Natives, London, Two Roads, 2019; R. Gildea, Empires of the Mind: The Colonial Past and the Politics of the Present, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2019; P. Gopal, Insurgent Empire, London, Verso, 2019;