Beth Ashton, teacher of Year 5 and 6 English in WHS Junior School, investigates Kagan structures and how this methodology helps to create an engaging classroom atmosphere focused on promoting effective learning.

“When teachers use Kagan structures they dramatically increase both the amount of active engagement and the equality of active engagement among students.”

Kagan, S. Structures Optimize Engagement. San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing. Kagan Online Magazine, Spring/Summer 2005

There is no doubt that creating a climate of active learning in the classroom contributes directly to the success and lasting impact on children’s development educationally.

As children progress through the key stages, the curriculum shifts in balance from skills to a more content-based approach. This can result in diminishing opportunities for lessons to be delivered with practical content. As a result, ensuring an active learning climate can be challenging.

Passive learning places focus on the teacher to dictate the learning environment, acting as the locus of control and knowledge within the classroom. Research has demonstrated that this approach results in poor knowledge retention and lasting issues for students in terms of taking ownership over their learning.

In terms of personal growth and the development of a lasting relationship with learning, this can result in pupils lacking the autonomy and independence to sustain their own studies.

With a whole-class ‘hands-up’ approach, pupils’ perception of their own ability can also be damaged.

“If the teacher has students raise their hands and calls on the students one at a time, students learn to compete for teacher’s attention. They are happy if a classmate misses, because it increases their own opportunity to receive recognition and approval”

Kagan, S. Kagan Structures for Emotional Intelligence

However, when time is of the essence and teachers are required to deliver a dense and complex curriculum, finding practical solutions to avoiding passive learning and ensuring active engagement in lessons can be difficult.

“The first critical question we ask is if the task we have set before our students results in a positive correlation among outcomes. Does the success of one benefit others?”

Kagan, S. Structures Optimize Engagement. San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing. Kagan Online Magazine, Spring/Summer 2005

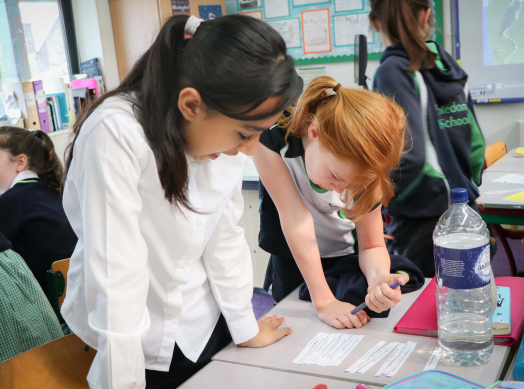

In order to combat passive learning in the classroom, Years 5 and 6 in WHS Juniors have been using Kagan interactive learning structures in English lessons to promote inclusive and engaged dialogue when engaging with texts. Over the course of the year, girls have demonstrated an improved ability to move between social groups easily within lessons. Focussing on social awareness and the ability to converse with their peer group effectively has meant that teachers have been able to reward a multitude of different skills, rather than just praising those girls who put their hand up.

Kagan is a system of cooperative learning structures, based on using peer support to engage pupils. Using a series of variety of different interactive structures, pupils are placed in mixed ability groups of four. Constructing these groups with an awareness of social dynamics and learning styles is vitally important.

Kagan structures require every student to participate frequently and approximately equally https://www.kaganonline.com/about_us.php

By encouraging students to work as a team, teachers are able to remove the elements of competition and insecurity within the classroom, replacing them with a culture of collaboration and mutual support. The ‘hands-up’, whole-class approach to lessons is removed and replaced with pupils learning and discussing questions as a group, and feeding back to other groups around the classroom. This is achieved by swapping different numbers and using strategies such as ‘round robin’ and ‘numbered heads together’.

For example, when analysing a poem in English, girls would work in mixed ability groups, trying to identify the use of symbolism and looking at its effect. After thinking time, each number would be given an allocated time to share their thinking. This could be organised with the most able student sharing last, so that they don’t automatically lead the conversation. In order to ensure the lower ability pupil remains engaged, they could be pre-warned that their number would be responsible for reporting the outcome of the group discussion to the rest of the class.

The round robin structure described above ensures that each pupil:

- has a role

- is given allocated and structured time to share their views

- is listened to by their peers

Importantly, the conversation is not dominated by one particular student. The option to opt out is also managed effectively by the teacher, by ensuring that pupils are aware of the high expectations around their engagement and contribution to class discussion.

“Group work usually produces very unequal participation and often does not include individual accountability, a dimension proven to be essential for producing consistent achievement gains for all students.”

Kagan, S. Structures Optimize Engagement. San Clemente, CA: Kagan Publishing. Kagan Online Magazine, Spring/Summer 2005

By using the Kagan interactive models, unstructured group discussions are removed from the classroom environment. Strategies such as ‘Timed Pair Share’ give discussion a scaffold. This means that pupils who usually demonstrate a dominant approach and tend to speak first, are able to develop the capacity to listen. Equally, students who tend to take a back-seat are guided through the process of sharing their thinking more readily.

The teacher is also able to allocate roles within groups with ease and adaptability according to the pupil’s number within the group. This ensures that dominant pupils are not able to control team discussions and feedback time, and less engaged pupils are drawn into participation through interaction with peers.

“If students in small groups discuss a topic with no ‘interaction rules’, in an unstructured way, often one or two students dominate the interaction. If, however, students are told they must take turns as they speak, more equal participation is ensured”

Kagan, S. A Brief History of Kagan structures.

As well as academic participation, Kagan can be a vital tool in improving social awareness and skills. The format of structured discussion time within class, results in clear social strategies being delivered to pupils through lesson content. Providing discussion in class with a framework also increases confidence and promotes risk-taking. These skills translate to the playground and, ultimately, the students’ life outside school and into the world of work.

Research shows that there is a strong correlation between social interaction and exchange of information. Generally, higher achieving students tend to form sub-groups within a cohort, creating enclaves where information is rapidly exchanged, and excluding those students they perceive as ‘lower ability’. This can result in those students who struggle feeling isolated and excluded, and ultimately disengaging from their studies. By using Kagan to scaffold and structure the sharing of information between children of different abilities, we can ensure that pupils of all abilities are gaining access to the social interactions which will ensure they make excellent progress.

A whole-class approach to questioning is proven to disengage a significant proportion of the class, whilst placing strain on the teacher. By passing ownership of the lesson to the students, through posing questions and allowing them to answer collaboratively, the teacher is able to take a step back and observe the learning process, taking feedback from each child through listening to their discussion.

By providing the teacher with the time and mental space to observe the lesson as it progresses, changes are able to be made over the course of the lesson, adapting to pupils needs. By using Kagan structures when tackling new learning, students are guided through the stages of learning through peer support. In the first stage of learning, pupils are able to work as a larger group, obtaining a significant amount of team support. Following this, pupils are then able to take on the problem in pairs, and finally, individually.

Using this format provides the more able pupils with the challenge of articulating their thinking to support their peers and provides those with barriers to learning with support of multiple different kinds within a lesson. Using established interactive structures means that the structures themselves are transferable across subjects, allowing them to be applied to all lessons. Having a readily available, student-led body of cooperative learning strategies embedded in the curriculum means that differentiation through discussion and peer support avoids a system of creating worksheets and allows pupils to ensure they are constantly being challenged, stretched and supported.

Follow @Juniors_WHS on Twitter

We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years.

We prefer ‘Stepping In’…… I fondly call my new cohort of Year 7s on their first day (or should I say term?), ‘turtles’…. their backpack has their life in it and appears to dwarf them as they wide-eyed, set off down school corridors navigating their way around what will be ‘home’ for the next 7 years. The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’

The crux of her book ‘Daring Greatly’

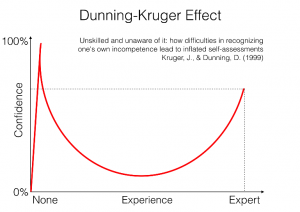

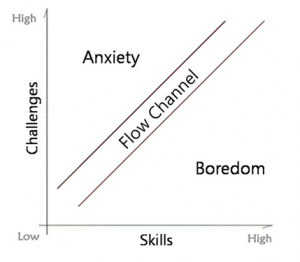

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience:

They say a little knowledge is a dangerous thing. If we consider the Dunning-Kruger effect (demonstrated on the diagram to the right) we might agree. The principle is that ‘knowledge without sufficient experience can lead to an overestimation of ability’. It is no surprise that Donald Trump has been nicknamed the ‘Dunning-Kruger President’ in articles by the New York Times, Bloomberg, and the Independent. I recall an interview where he tries to explain uranium to his audience:

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

A freezing cold 4am start in the Atlas Mountains sees our tired little group tackle the last 1000 meters or so of Africa’s second highest peak, Mount Toubkal. As pitch black gives way to pink dawn we climb on, and rubble and dust soon become ice and rock. At the 4167-metre-high summit the air is thin, but the view and sense of achievement is as extraordinary as the sky is now rich blue. Looking south standing on a flat rock I am confronted with Africa sprawling hazy to the horizon, so I hold aloft an imaginary Simba and sing ‘The Circle of Life’, loudly. I blame the altitude.

A freezing cold 4am start in the Atlas Mountains sees our tired little group tackle the last 1000 meters or so of Africa’s second highest peak, Mount Toubkal. As pitch black gives way to pink dawn we climb on, and rubble and dust soon become ice and rock. At the 4167-metre-high summit the air is thin, but the view and sense of achievement is as extraordinary as the sky is now rich blue. Looking south standing on a flat rock I am confronted with Africa sprawling hazy to the horizon, so I hold aloft an imaginary Simba and sing ‘The Circle of Life’, loudly. I blame the altitude. For the Romantics, mountains were endlessly fascinating. Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Ruskin et al developed language and ideas which soon became identified as seeking ‘the sublime.’ Perhaps this was by way of a reaction against the nuts and bolts, dirt, detail, grime and grease of the Industrial Revolution. Shelly’s beautiful line ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ certainly gives us a context of vast topographical scale, with the peaks (high above us mere humans beings) themselves dwarfed by the expanse of the heavens. For Shelly, as for the other Romantics, thinking about and visiting mountains allowed for ideas and encounters on an epic scale. Mary Shelley offers us perhaps the most vivid mountains in all romantic literature in her novel Frankenstein. Given the nineteenth-century’s literary love affair with mountain imagery, it is perhaps no surprise that our very own Kitty Ramsey (author of our school song) saw Wimbledon High girls throwing off corsets and crinolines and hiking up those ‘unconquered peaks’ of their own futures. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is full of peaks to climb over, go around or even go through, and, to my mind, even Jay Gatsby climbing the stairs to survey the extravagance of his party below in ‘The Great Gatsby’ or King Kong scaling the needle-like radio mast of the Empire State ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ (Hollywood starlet in hand) shows a (largely male-centric) mountain mythology looming large comfortably into the twentieth century.

For the Romantics, mountains were endlessly fascinating. Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Ruskin et al developed language and ideas which soon became identified as seeking ‘the sublime.’ Perhaps this was by way of a reaction against the nuts and bolts, dirt, detail, grime and grease of the Industrial Revolution. Shelly’s beautiful line ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ certainly gives us a context of vast topographical scale, with the peaks (high above us mere humans beings) themselves dwarfed by the expanse of the heavens. For Shelly, as for the other Romantics, thinking about and visiting mountains allowed for ideas and encounters on an epic scale. Mary Shelley offers us perhaps the most vivid mountains in all romantic literature in her novel Frankenstein. Given the nineteenth-century’s literary love affair with mountain imagery, it is perhaps no surprise that our very own Kitty Ramsey (author of our school song) saw Wimbledon High girls throwing off corsets and crinolines and hiking up those ‘unconquered peaks’ of their own futures. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is full of peaks to climb over, go around or even go through, and, to my mind, even Jay Gatsby climbing the stairs to survey the extravagance of his party below in ‘The Great Gatsby’ or King Kong scaling the needle-like radio mast of the Empire State ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ (Hollywood starlet in hand) shows a (largely male-centric) mountain mythology looming large comfortably into the twentieth century.

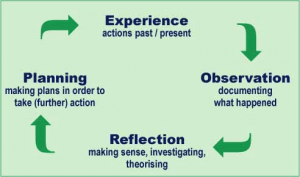

To summarise Schon’s argument; the reflective practitioner in any given task can recognise confusing or unique (positive or negative) events that happen during practice. The ineffective practitioner, says Schon, is confined to repetitive and routine practice, neglecting opportunities to think about what she/he is doing. However, Duckworth’s important point about remaining optimistic and cheerful when we need to be reflective is also worth remembering here. Schon would no doubt have championed Captain Jack Sparrow’s mantra; the problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.

To summarise Schon’s argument; the reflective practitioner in any given task can recognise confusing or unique (positive or negative) events that happen during practice. The ineffective practitioner, says Schon, is confined to repetitive and routine practice, neglecting opportunities to think about what she/he is doing. However, Duckworth’s important point about remaining optimistic and cheerful when we need to be reflective is also worth remembering here. Schon would no doubt have championed Captain Jack Sparrow’s mantra; the problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.