Toward the Unknown Region[1] – Mr. Nicholas Sharman, Head of Design & Technology looks at whether integrating STEAM into the heart of a curriculum develops skills required for careers that do not currently exist.

The world of work has always been an evolving environment. However, it has never been more pertinent than now; according to the world economic forum, 65% of students entering primary school today will be working in jobs that do not currently exist[2].

As educators, this makes our job either extremely difficult, pointless or (in my view) one of the most exciting opportunities that we have been faced with for nearly 200 years since the introduction of the Victorian education system. The idea of relying solely on a knowledge-based education system is becoming outdated and will not allow students to integrate into an entirely different world of work. Automation and Artificial Intelligence will make manual and repetitive jobs obsolete, changing the way we work entirely. Ask yourself this: could a robot do your job? The integration of these developments is a conversation all in its own and one for a future post.

So, what is STEAM and why has it become so prominent in the UK education system?

The acronym STEM was (apparently) derived from the American initiative ‘STEM’ developed in 2001 by scientific administrators at the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF)[3]. The addition of the ‘A’ representing the Arts, ultimately creating Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Maths. Since the introduction of STEM-based curriculums in the US, the initiative has grown exponentially throughout the globe, with the UK education system adopting the concept.

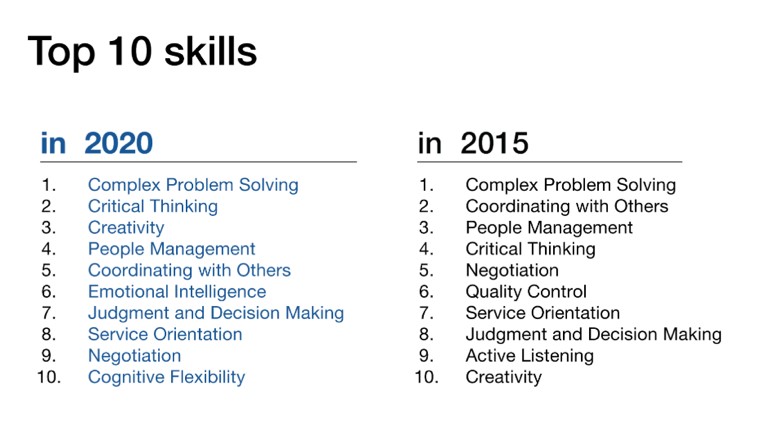

So why STEAM and what are the benefits? STEAM education is far more than just sticking subject titles together. It is a philosophy of education that embraces teaching skills and subjects in a way that resembles the real world. More importantly, it develops the skills predicted to be required for careers that currently do not exist. What are these skills and why are they so important?

Knowledge vs Skills

When we look at the education systems from around the world there are three that stand out. Japan, Singapore and Finland have all been quoted as countries that have reduced the size of their knowledge curriculum. This has allowed them to make space to develop skills and personal attributes. Comparing this to the PISA rankings, these schools are within the top 5 in the world and in Singapore’s case, ranked No1[4].

I am sure we cannot wholly attribute this to a skills-focused curriculum; however, it does ask the question – what skills are these schools developing and how much knowledge do we need?[5],[6]

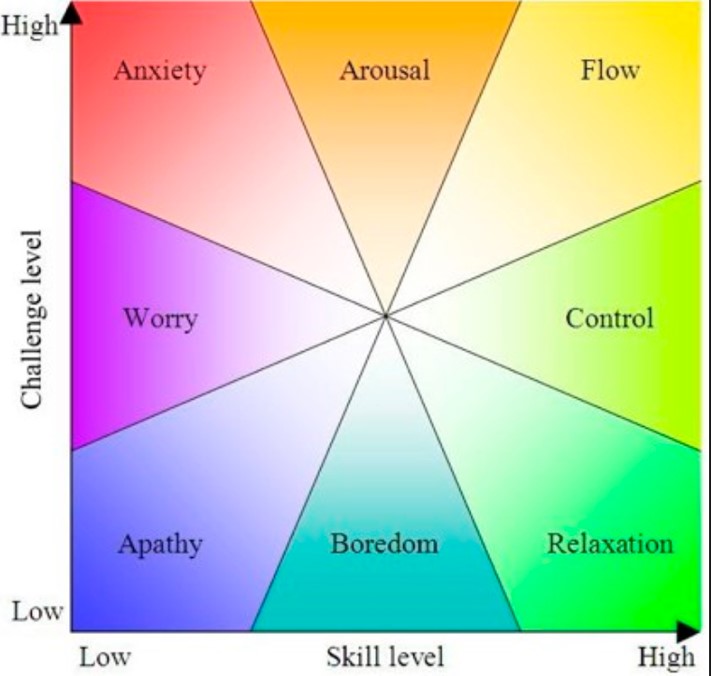

- Mental Elasticity – having the mental flexibility to think outside of the box, see the big picture and rearrange things to find a solution.

- Critical Thinking – the ability to analyse various situations, considering multiple solutions and making decisions quickly through logic and reasoning.

- Creativity – robots may be better than you may at calculating and diagnosing problems, however, they are not very good at creating original content, thinking outside the box or being abstract.

- People Skills – the ability to learn how to manage and work with people (and robots), having empathy and listening

- SMAC (social, mobile, analytics and cloud) – learning how to use new technology and how to manage them

- Interdisciplinary Knowledge – understanding how to pull information from many different fields to come up with creative solutions to future problems.

All of the above skills are just predictions. However, the list clearly highlights that employers will be seeking skill-based qualities, with this changing as future jobs develop and materialise. So do we need knowledge?

Well, of course we do – knowledge is the fundamental element required to be successful in using the above skills. However, as educators, we need to consider a balance of how we can make sure our students understand how important these skills will be to them in the future when an exam grade based on knowledge could be irrelevant to employers.

What subjects promote these skills?

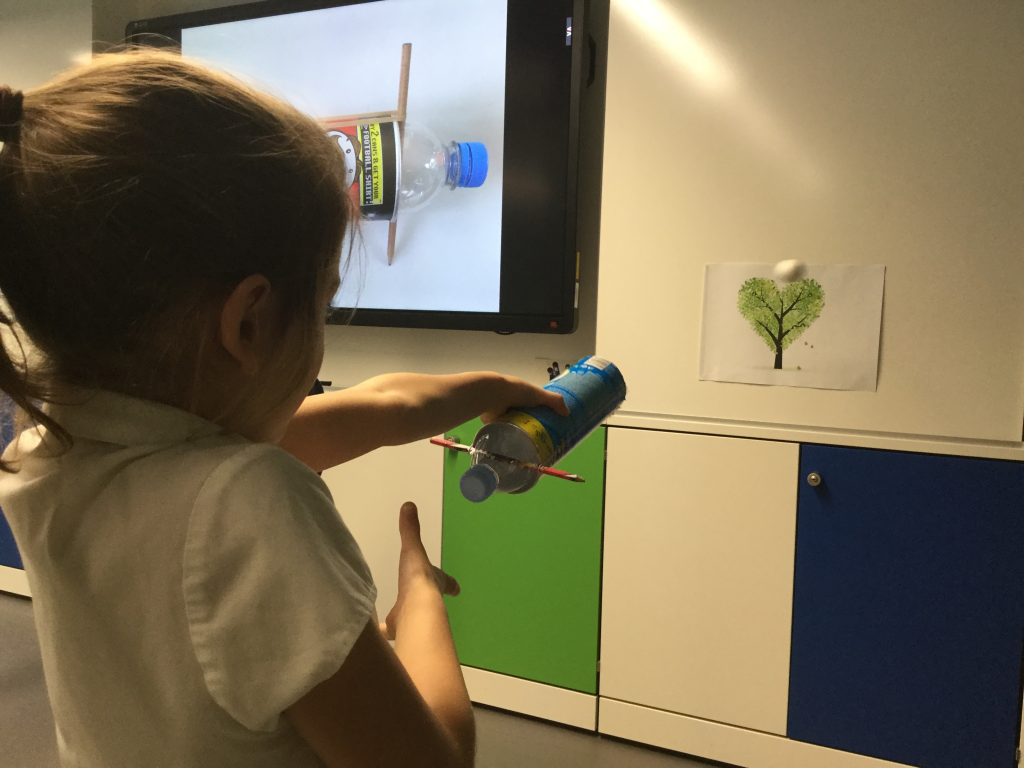

As a Technologist, I believe there has never been a more important time in promoting and delivering the Design & Technology curriculum. The subject has for too long been misrepresented and had a stigma hanging around it due to previous specifications and people’s experiences, comments such as ‘so you teach woodwork then?’ really do not give justice to the subject.

With the introduction of the new curriculum, allowing students more opportunity to investigate and build these future skills, the subject has never been more relevant. Looking at the list of promoted skills, I cannot think of another subject that not only promotes these skills but also actively encourages the integration into every lesson. Do not get me wrong, all subjects are as equally important. Design & Technology is a subject that is able to bring them all into real-world scenarios. If we think about the knowledge that is developed in Science for example – where students can look at material properties and their effect on the user’s experience, or Religious Studies and how different signs, symbols or even colours can have different meanings in cultures affecting the design of a fully inclusive product – they can all be related to Design and Technology in one way or another.

Comparing the Design & Technology curriculum to the future skills list, we can break down the different skills it develops. It encourages mental elasticity through challenging student’s ideas and concepts, thinking differently to solve current and real-life problems. It allows students to develop critical thinking, through challenging their knowledge and understanding; ensuring students develop the ability to solve problems through investigation, iteration and failure, ultimately building resilience. It goes without saying that the subject not only encourages creativity but allows students to challenge concepts and ideas through investigating and questioning. Furthermore, it teaches the concept of ‘design thinking’ and collaborative working, allowing students to develop people skills, understanding how people work, interact and think; enhancing empathy and understanding. As technology progresses the subject follows suit, permitting students to implement and understand how new and emerging technologies are embedded, not only into the world of design but the Social, Moral and environmental effects they create. Lastly and probably most importantly, is how the subject teaches interdisciplinary knowledge. I like to describe Design & Technology as a subject that brings knowledge from all areas of the curriculum together, the creativity and aesthetics from Art, the application of Maths when looking at anthropometrics, tolerances or even ratios, how Religious Studies can inform and determine designs, how science informs and allows students to apply theory, or even the environmental impact Geography can show. I could go on and explain how every subject influences Design & Technology in one way or another, although, more importantly, it shows how we need to look at a more cohesive and cross-curricular curriculum; when this happens the future skills are inherently delivered in a real-world application.

Looking back at the question at the start of this article, we can start to conclude why having the concept of STEAM at the heart of a school environment is so important. However, it is not good enough to just ‘stick’ subjects together, there has to be a bigger picture where knowledge and skills are stitched together like a finely woven tapestry. Ideally, we would look at the primary education system, where we remove subject-specific lessons, develop co-teaching, learning that takes place through projects bringing elements from all subjects in to cohesive projects; teachers would become facilitators of learning, delivering knowledge not in a classroom but in an environment that allows more autonomous research and investigation. However, until the exam system changes, this is not going to fully happen.

So what could we be doing more? I believe we should be focusing on more cross-curricular planning, developing skills application and using knowledge to enhance learning. By developing a curriculum centred around a STEAM approach, we can start to develop the skills required for our students and the careers of the future.

References:

At school, I lead the annual trip for students in Year 10 – Year 13 to Poland, where we visit Auschwitz concentration camp and Oskar Schindler’s factory. When he died, Oskar Schindler asked to be buried in Jerusalem, facing the Mount of Olives and his grave is visited by millions each year. On my second day, I searched for his grave. In a way, it was closing a circle. I had visited his factory in Poland, listened to many Schindler survivor testimonies and, of course, watched the film. Here was my opportunity to pay tribute to that awe-inspiring man, who saved so many. His grave had stones placed on top of it, a Jewish tradition to honour the dead. Later in the week, I visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to the Shoah (Holocaust) and saw his tree planted in the ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ – a row of trees placed in memory of all the non–Jews who helped save the lives of Jewish people during the Shoah.

At school, I lead the annual trip for students in Year 10 – Year 13 to Poland, where we visit Auschwitz concentration camp and Oskar Schindler’s factory. When he died, Oskar Schindler asked to be buried in Jerusalem, facing the Mount of Olives and his grave is visited by millions each year. On my second day, I searched for his grave. In a way, it was closing a circle. I had visited his factory in Poland, listened to many Schindler survivor testimonies and, of course, watched the film. Here was my opportunity to pay tribute to that awe-inspiring man, who saved so many. His grave had stones placed on top of it, a Jewish tradition to honour the dead. Later in the week, I visited Yad Vashem, the Israeli memorial to the Shoah (Holocaust) and saw his tree planted in the ‘Avenue of the Righteous’ – a row of trees placed in memory of all the non–Jews who helped save the lives of Jewish people during the Shoah.