Rebecca Brown, Maths Teacher at Wimbledon High School, explores the benefits of creating a positive stereotype.

“I’m great at Maths”

A statement seldom heard. In fact, quite the opposite, particularly when introducing yourself as a Maths Teacher!

Unfortunately, many people hold strong negative beliefs about maths that they do not hold about other subjects. I often hear intelligent, highly educated adults state (almost with pride) “I was never any good at maths”. Many people seem to have been traumatised by maths, further fuelled by misguided beliefs about mathematics and intelligence. Their experience of learning Maths varied drastically from the dynamic, exciting and personalised maths teaching of today. Researchers found that when mothers told their daughters “I was no good at Maths in school” their daughters’ achievement immediately went down (Eccles and Jacobs, 1986[1]). But why is it considered socially acceptable to be bad at Maths? And more importantly what message does it give the women of the future if their own parents, teachers and influencers unashamedly comment on how bad they were at Maths at school – or still are?

Fifteen is the exact age a girl loses her interest in Maths (Jones, 2018[2]). I am not referring to Maths anxiety, that Ashcroft (2002) defined as a ‘feeling of tension, apprehension or fear that interferes with maths performance’, but to the time girls decide that Maths is just ‘not for them’. Recent figures show that after GCSE, 20% fewer girls than boys continue studying Maths. Yet in junior schools, Maths is often cited as a favourite subject for many girls. So why are girls not continuing with maths and what can we do about it?

Why is Maths so important?

Maths is all around us. It is in everything we do and everywhere we go. From Music to Sport, from Geography to Biology. Coding, Algorithms, Programming, Problem-solving. It is our future. It is in the technology in our hands, on our laps and on our screens. It is shaping our world and is the beauty that surrounds us.

When it comes to Maths at A Level, girls account for just 39% of the national cohort. (Although at Wimbledon High School we’re proud that over 55% of the sixth form opt to continue with Maths after GCSE).

A female underrepresentation as a nation at A Level means an underrepresentation of women in careers that involve Maths. By not taking Maths, girls limit their access to some of the more challenging, interesting and lucrative careers. For example, recent IFS research[3] suggests that, compared to the average female graduate, five years after graduation women with a Maths degree earn 13.4% more; those with an engineering degree earn 9.7% more, and those with an economics degree – another subject in which girls are significantly underrepresented and for which Maths is often a gateway subject – earn 19.5% more. Research has also shown that students taking advanced Maths classes learn ways of working and thinking – especially learning to reason and be logical – that make them more productive in their jobs (Rose and Betts 2004[4]).

Engineering jobs are predicted to grow at double the rate of other occupations, but there is currently a crisis of female underrepresentation in STEM Science, Technology, Engineering and Maths careers; women comprise up only 14.4% of the total STEM population (WISE[5] ). This means that potential female candidates will have not only limited their own life chances, but also deprived the STEM disciplines of the thinking and perspectives that girls and women can bring. (Boaler, 2014a[6]). The current UK goal is for at least 30 % of people working in STEM careers to be women.

It is not just the raw state of Maths that is useful for the future, it is the skills that develop as part of learning the wonders of Maths; problem-solving, critical and lateral thinking, quantitative and analytical reasoning to name a few, that are part of the attraction. After all, we are preparing our children for jobs that do not yet exist!

The negative connotations that prevail about Maths seldom come from harmful teaching practices; they come from one idea, which is very strong, permeates many societies (although notably absent in countries such as China and Japan) and is at the root of maths failure and underachievement: that only some people can be good at Maths (Boaler, 2016 [7])

Growth Mindset in Maths

A ‘Growth Mindset’ in Maths is crucial. Perseverance, grit and resilience, are common skills identified in successful students in any field, made widely known by the work of Duckworth et al. (2007[8]). ‘Economists refer to them as non-cognitive skills, psychologists call them personality traits and the rest of us sometimes think of them as character’ (Tough, 2013[9]). In Maths these skills are even more fundamental.

In her 2006 book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Carol Dweck summarised her evidence from decades of research with differently-aged subjects, showing that when students develop what she has called a ‘growth mindset’ then they believe that intelligence and ‘smartness’ can be learned and that the brain can grow from exercise.

Everyone has a mindset, a core belief about how they learn (Dweck, 2006b[10]). People with a ‘growth mindset’ are those who believe that smartness increases with hard work, whereas those with a ‘fixed mindset’ believe you can learn things, but you can’t change your basic level of intelligence.

The fixed mindset thinking that is so damaging, cuts across the achievement spectrum, and some of the students most damaged by these beliefs are high-achieving girls (Dweck, 2006a). General mindset interventions can be helpful, but if students return to approaching maths in the same way they always have then the growth mindset about maths erodes away (Boaler, 2016[11]).

So, our focus should be on developing strong Mathematical mindsets within the classroom and at home.

What holds girls back from Maths?

Confidence, self-belief and mindset. It is lack of confidence and not lack of ability that deters girls from taking Maths after GCSE. Lack of self-confidence can limit a girl’s learning and her potential. We need to develop their confidence and self-esteem and teach them to not be perfect! Getting an answer incorrect does not mean failure. A mistake is a portal to better understanding, discovery and part of an important learning journey. Mistakes are invaluable lessons and help up us to develop. Generation Z is under pressure to look and act a certain way, a problem amplified by social media. Role models are extremely important to young people and girls are often more influenced, judging themselves by more restrictive standards reinforced by the media and society at large, further reducing their confidence in the classroom.

When it comes to Maths, girls rate their abilities markedly lower than boys, even when there is no observable difference between them, according to Florida State University researchers.[12] The authors note boys are encouraged from a young age to pursue challenge, including the risk of failure, while girls tend to pursue perfection.

‘Sticking with it’ is something girls need to be encouraged to learn, says Reshma Saujani, founder and CEO of Girls Who Code, whose mission is to close the gender gap in technology. “We have to rethink the way we raise our girls. We have to teach girls to be imperfect. Teach them to be brave and not perfect” (Saujani, R 2016[13] ).

As leaders in educating girls, at the GDST, we focus on developing the skills and character to prepare them for the future. As teachers, we are dedicated to inspiring every one of our girls and trained to unleash their potential. Especially in Maths.

At GDST Schools, girls can learn without limits. We can influence the next generation of women to have a positive view of maths. We can all create and believe in a new stereotype– All girls are born great at Maths.

References:

[1] Eccles, J. & Jacobs, J (1986) Social forces shape math attitudes and performance.

[2] Jones, P. (December, 2018). Phylecia Jones: All Girls Are Great at Math [Video File] Retrieved from https://www.phyleciajones.com/tedx/

[3] https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13036

[4] Rose, H., & Betts, J.R (2004). The effect of high school courses on earnings. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86 (2), 497-513

[5] https://www.wisecampaign.org.uk/statistics/women-in-the-uk-stem-workforce/

[6] Boaler, J. (2014a). Changing the conversation about girls and STEM. Washington DC:The White House.

[7] Boaler, J (2016). Mathematical Mindsets. Unleashing Students’ Potential Through Creative Maths, Inspiring Messages and Innovative teaching.

[8] Duckworth AL, Peterson C, Matthews MD, Kelly DR. Pers Soc Psychol. 2007. Grit, perseverance, and passion for long term goals.

[9] Tough, Paul. 2013. How Children Succeed.

[10] Dweck, C.S (2006b). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

[11] Boaler, J (2016). Mathematical Mindsets.

[12] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/04/170406121532.htm Florida State University. “Under challenge: Girls’ confidence level, not math ability hinders path to science degrees.” ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, 6 April 2017. <www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/04/170406121532.htm>.

[13] Sujani – Teach girls bravery not perfection. https://www.ted.com/talks/reshma_saujani_teach_girls_bravery_not_perfection?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

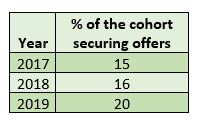

These are just some of the ways in which our programme supports and empowers our girls. In an increasingly competitive environment, we have managed to increase the percentage of the cohort securing offers year on year. This bucks the national trend for independent schools and we think our support programme has helped our Oxbridge success grow. We continue to work with our partner schools to develop our programmes to encourage candidates to pursue an application and to support them wholeheartedly throughout the process.

These are just some of the ways in which our programme supports and empowers our girls. In an increasingly competitive environment, we have managed to increase the percentage of the cohort securing offers year on year. This bucks the national trend for independent schools and we think our support programme has helped our Oxbridge success grow. We continue to work with our partner schools to develop our programmes to encourage candidates to pursue an application and to support them wholeheartedly throughout the process.

The biggest impact of Gatsby has been to act as a framework on which we have built our brand new Striding Out programme, which embraces the concept of a truly holistic approach to career and higher education preparation.

The biggest impact of Gatsby has been to act as a framework on which we have built our brand new Striding Out programme, which embraces the concept of a truly holistic approach to career and higher education preparation.