Talia, Year 8, explores the concept of ideasthesia and how our understanding of it has changed over time.

To understand what ideasthesia is, first we must look to its cousin, synaesthesia. The word synaesthesia literally translates as ‘union of senses’ and comes from the Greek words ‘syn’ which means ‘union’ and ‘aesthesis’ which means ‘senses’. It is a phenomenon in which some people associate external stimuli to a sense. For example, people with letter-colour synaesthesia can see individual letters as different colours. Other types of synaesthesia include musical sounds-colours, pain-colours, vision-tastes and many more.

The original understanding of synaesthesia was taken almost directly from the translation of the word. Scientists thought the sensory parts of synesthetes’ (people who suffer from synaesthesia) brain were somehow connected and, when given certain stimuli, would trigger each other. Later studies made on synesthetes suggested that this theory was not entirely correct; in one study, synesthetes made new synesthetic associations to letters they had never seen before. These associations were made within seconds which is not enough time to form a new physical connection between the colour representation and letter representation areas in the brain so this proved that the senses could not be linked.

In another study, letter-colour synesthetes were shown what could be a ‘zero’ or an ‘o’. When the shape was shown in the context of letters, the synesthetes interpreted the shape as the letter ‘o’ and viewed it as one colour; when the shape was shown in the context of numbers, the synesthetes interpreted the shape as the number ‘zero’ and viewed it as a different colour even though it was the exact same shape as before. This study shows that the inducer of these experiences is semantic rather than purely sensory.

Croatian cognitive neuroscientist, Danko Nikolic, came up with the name ‘ideasthesia’ for this new theory coming from the Greek word’s ‘idea’ meaning ‘idea’ or ‘concept’, and ‘aesthesis’ meaning ‘senses’ – it translates to ‘sensing ideas’. During Nikolic’s research, a woman came to him with a very rare case of synaesthesia called mirror-speech synaesthesia. She said “I hear any sound made by a human and it feels like I’m making that sound… in stomach, body, throat and mouth…but only in my mind. I don’t get throat pain for ‘singing’ too much.” Nikolic ran some tests on this woman to dig deeper into her curious case. He discovered that, when the woman was told that an animal was making a noise, she wouldn’t get the sensations. However, if she played the exact same noise again and was told that a human made it, she would get the sensations.

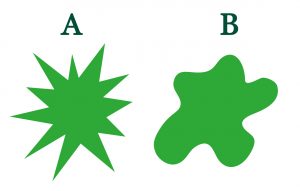

The woman in Nikolic’s study appears to be a rare case but there is a bit of ideasthesia in everyone. When asked to name one shape ‘Bouba’ and one shape ‘Kiki’, most subjects chose to name shape A ‘Kiki’ and shape B ‘Bouba’ based on the shape that the mouth makes as it is forming these words and how the words sound – this shows that we all have a basis of ideasthesia in all of us – we link concepts to sensory stimuli whether it’s shapes, colours or others. Furthermore, the subjects went on to describe ‘Kiki’ as nervous and clever, whereas ‘Bouba’ was described as lazy and slow.

Perhaps this theory of ideasthesia could help with the long-lasting mind-body conundrum: is the mind a separate entity that controls our body externally? Or, if it is part of the brain, how does it translate the input of physical senses into the non-physical state of thoughts? Some scientists are now saying that our mistake is assuming that there is a barrier between these two functions – that thoughts and senses are linked together in a complex network, comparable to our language network.

The traditional view is that the senses grasp a collection of vibrations or colours which our brain translates into the sound of a voice or the colours of a flower. Ideasthesia suggests that these processes happen as one – our sensory perceptions are based on our conceptual understanding that we hold of the world. This is what helps us understand metaphors that make no logical sense, such as the comparison of a cushion to air based on the shared sensation of fluffiness, and the apparent weightlessness of them both.