Dr John Parsons, Director of Sixth, shares a recent assembly to the Senior School with us.

‘Then forward to th’unconquered peaks above’

The School Song – Kitty Ramsay (The Duchess of Athol)

A freezing cold 4am start in the Atlas Mountains sees our tired little group tackle the last 1000 meters or so of Africa’s second highest peak, Mount Toubkal. As pitch black gives way to pink dawn we climb on, and rubble and dust soon become ice and rock. At the 4167-metre-high summit the air is thin, but the view and sense of achievement is as extraordinary as the sky is now rich blue. Looking south standing on a flat rock I am confronted with Africa sprawling hazy to the horizon, so I hold aloft an imaginary Simba and sing ‘The Circle of Life’, loudly. I blame the altitude.

A freezing cold 4am start in the Atlas Mountains sees our tired little group tackle the last 1000 meters or so of Africa’s second highest peak, Mount Toubkal. As pitch black gives way to pink dawn we climb on, and rubble and dust soon become ice and rock. At the 4167-metre-high summit the air is thin, but the view and sense of achievement is as extraordinary as the sky is now rich blue. Looking south standing on a flat rock I am confronted with Africa sprawling hazy to the horizon, so I hold aloft an imaginary Simba and sing ‘The Circle of Life’, loudly. I blame the altitude.

*

I’m a mountain fan – wild, uncompromising, inaccessible, difficult (that’s mountains, not me). Mountains are part of our collective experience and our consciousness, both geographically and metaphorically. They represent the impossible made possible and the unconquerable conquered. Our mythology is peppered with cameos from mountains; the ancient Greek gods live on Mount Olympus; the same gods punish Sisyphus by forcing him to push a boulder to the top of a mountain for eternity; and the gods gather on Mount Ida to watch the Trojan War. In the Hindu faith, Shiva lives at the top of a mountain, and in Islam Mohamed receives his first revelation on Mount Hira (not to mention examples from Buddhism and Jainism). In the Judeo-Christian tradition mountains again loom large; Noah’s ark comes to rest on the top of a mountain; Moses receives the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai; we see Christ giving his sermon at higher climbs, and we first see him revealed as the son of God on the top of Mount Tabor before his final hours play out on the Mount of Olives. In Inca mythology, mountain tops are portals to the gods, and the ancient Taranaki people native to New Zealand anthropomorphised their mountains. There is a sense in all of this that the remoteness of mountain tops brought ancient peoples as close to their god(s) as was possible. Mountains have long been places of revelation and transformation.

For the Romantics, mountains were endlessly fascinating. Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Ruskin et al developed language and ideas which soon became identified as seeking ‘the sublime.’ Perhaps this was by way of a reaction against the nuts and bolts, dirt, detail, grime and grease of the Industrial Revolution. Shelly’s beautiful line ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ certainly gives us a context of vast topographical scale, with the peaks (high above us mere humans beings) themselves dwarfed by the expanse of the heavens. For Shelly, as for the other Romantics, thinking about and visiting mountains allowed for ideas and encounters on an epic scale. Mary Shelley offers us perhaps the most vivid mountains in all romantic literature in her novel Frankenstein. Given the nineteenth-century’s literary love affair with mountain imagery, it is perhaps no surprise that our very own Kitty Ramsey (author of our school song) saw Wimbledon High girls throwing off corsets and crinolines and hiking up those ‘unconquered peaks’ of their own futures. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is full of peaks to climb over, go around or even go through, and, to my mind, even Jay Gatsby climbing the stairs to survey the extravagance of his party below in ‘The Great Gatsby’ or King Kong scaling the needle-like radio mast of the Empire State ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ (Hollywood starlet in hand) shows a (largely male-centric) mountain mythology looming large comfortably into the twentieth century.

For the Romantics, mountains were endlessly fascinating. Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Ruskin et al developed language and ideas which soon became identified as seeking ‘the sublime.’ Perhaps this was by way of a reaction against the nuts and bolts, dirt, detail, grime and grease of the Industrial Revolution. Shelly’s beautiful line ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ certainly gives us a context of vast topographical scale, with the peaks (high above us mere humans beings) themselves dwarfed by the expanse of the heavens. For Shelly, as for the other Romantics, thinking about and visiting mountains allowed for ideas and encounters on an epic scale. Mary Shelley offers us perhaps the most vivid mountains in all romantic literature in her novel Frankenstein. Given the nineteenth-century’s literary love affair with mountain imagery, it is perhaps no surprise that our very own Kitty Ramsey (author of our school song) saw Wimbledon High girls throwing off corsets and crinolines and hiking up those ‘unconquered peaks’ of their own futures. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is full of peaks to climb over, go around or even go through, and, to my mind, even Jay Gatsby climbing the stairs to survey the extravagance of his party below in ‘The Great Gatsby’ or King Kong scaling the needle-like radio mast of the Empire State ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ (Hollywood starlet in hand) shows a (largely male-centric) mountain mythology looming large comfortably into the twentieth century.

Mountains as Metaphor

We talk of having a mountain of work to do and are idiomatically warned not to make mountains out of mole hills. One of the first ever self-help books by one aptly named Samuel Smiles (1859) feeds off the mountain frenzy appearing in the poems and writings of the time. Smiles writes, ‘it is not ease but effort – not facility but difficulty that makes men… sweet indeed are the uses of adversity… they reveal to us our powers… without difficulty we would be worth less… the road to success is steep to climb.’ According to Smiles, those who took on and surmounted difficulties ended up bettering themselves. This was not advice for lazy people. It speaks of its time; that by sheer effort men (and he was clearly talking in terms of gender here, not species) could rise above social class and make something of themselves. By hard work anything was possible – a sort of Victorian version of Marvin Gaye’s Ain’t No Mountain High Enough. Inadvertently, of course, Smiles and others like him put ideas in women’s heads in the decades that followed; that with perseverance and hard graft women, too, could climb or even move mountains. In Rogers and Hammerstein’s 1959 musical The Sound of Music, the Mother Superior exhorts Maria to ‘Climb every mountain.’ That Maria and her new family physically do just that at the end of the show is beside the point. She is talking in far deeper terms; you will meet difficulties, so scale them and do not give in. There is clearly a parallel in all of this with, for example, the recent work of Angela Duckworth on ‘Grit’ and Carol Dweck’s research into ‘Growth Mindset’; success is borne of effort.

Rising to the Challenge

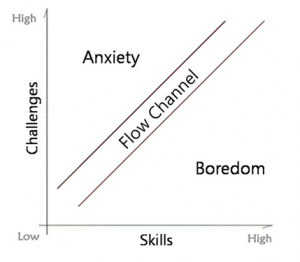

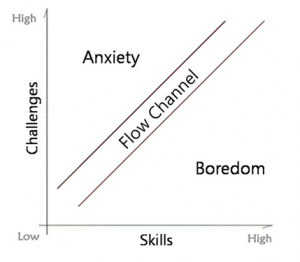

Climbing mountains is hard work, requiring focus and engagement. Mountaineers often talk in terms of being unaware that time has passed as they climb. Arguably, it is in this state when we move closest to achieving our goals and when we are at our maximum effectiveness. For Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) this was the ‘zone of proximal development’, and for Hungarian psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (born in the year of Vygotsky’s death), this was defined as ‘flow’. ‘Flow’ (see right) as described by Csikszentmihalyi is certainly an attractive and accessible theory, seeking to identify the ‘sweet spot’ (my words, not Csikszentmihalyi’s) when the task at hand is just challenging enough (y) to be achievable given the skill level of a person (x). If a task is too challenging for our level of skill, we become anxious; if it is not challenging enough we are most likely to become bored or disengaged.

It is, writes Csikszentmihalyi, at this intersection of challenge and skill where our most active and deep learning experiences occur, but also where the activity is most enjoyable. Indeed, his studies detail consistent occurrences of participants being unaware of time passing when they are ‘in flow,’ perhaps proving the old saying ‘time flies when you’re having fun.’ Recent research from Philip Gable and Brian Pool at the University of Alabama sets out to explore this idea further, and their conclusion offers a twist; according to Gable and Pool, time flies when we have goal-oriented fun. Gable concludes that ‘although we tend to believe that time flies when we’re having a good time, these studies indicate what it is about the enjoyable time that causes it to go by more quickly. It seems to be the goal pursuit or achievement-directed action we’re engaged in that matters. Just being content or satisfied may not make time fly but being excited or actively pursuing a desired object can’ (Psychological Science, August 2012).

As I climbed a seemingly endless 47-degree gradient of the final ascent of Italy’s majestic Gran Paradiso mountain last summer (I know it was 47 degrees because I got my iPhone out to measure it – shortly before it shut down from the cold), I was utterly unaware of how long I had been walking. Twenty minutes, two hours – longer? Genuinely, I had lost all concept of time. I was neither anxious nor bored, and the task at hand (or rather under foot) was on the edge of being just a little too challenging for my skill set. And I was having the time of my life. Of course, we can experience the same at work, in the classroom and in the exam hall.

Falling and Failing

Doing anything hard requires a conscious effort to move out of a comfort zone and risk failing. American psychologist Angela Duckworth terms the specific quality at play in such situations ‘grit,’ and defines this as ‘passion and perseverance for long-term goals’ (2016).

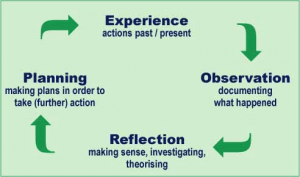

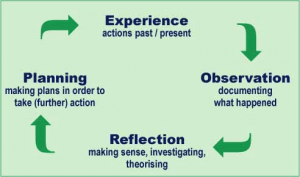

The idea of getting better at something by simply plodding along relentlessly until it is mastered takes in Csikszentmihalyi’s idea of ‘flow’, but, crucially, Duckworth’s thinking seems to chime with Gable & Pool in her assertion that we need a goal in the first place – a summit. To find Csikszentmihalyi’s flow we must inevitably make mistakes and reflect on them. In his seminal book The Reflective Practitioner (1983), Donald Schon (1930-1997) breaks down what might in fact happen in that reflective moment – the failure occurring in the ‘experience’ part of his diagram, below.

To summarise Schon’s argument; the reflective practitioner in any given task can recognise confusing or unique (positive or negative) events that happen during practice. The ineffective practitioner, says Schon, is confined to repetitive and routine practice, neglecting opportunities to think about what she/he is doing. However, Duckworth’s important point about remaining optimistic and cheerful when we need to be reflective is also worth remembering here. Schon would no doubt have championed Captain Jack Sparrow’s mantra; the problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.

To summarise Schon’s argument; the reflective practitioner in any given task can recognise confusing or unique (positive or negative) events that happen during practice. The ineffective practitioner, says Schon, is confined to repetitive and routine practice, neglecting opportunities to think about what she/he is doing. However, Duckworth’s important point about remaining optimistic and cheerful when we need to be reflective is also worth remembering here. Schon would no doubt have championed Captain Jack Sparrow’s mantra; the problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.

Our young people – as all emerging adult generations have done – must forget all about things being ‘insurmountable’, and respond to difficulty and failure with resilience, cheerfulness and a real quality of toughness. Failure is, after all, inherent in doing difficult things, from Maths tests to mountains.

Concluding Thoughts

As educators we seek to give young people opportunities for ‘flow’ moments in their academic learning, recognising the importance of that state in cementing deep learning. But this will inevitably be risky from time to time. Mountains expect us to take risks if we are to conquer them, but also to take care. They ask us slowly but consistently to put one foot in front of the other as we gain height. Despite meticulous planning, there will always unexpected obstacles on the way up, and we must acknowledge (and expect) these and respond calmly and decisively, and ask someone who knows more about climbing mountains we do to help. We must all pause from time to time to look back and see just how far we’ve come. We can’t and mustn’t spend the whole time looking at our feet – eyes on the detail – just as we can’t always be focused on the summit. Rather, we should always remember to take a moment to look back and take in the view.

Dr John Parsons, March 2018 (based on a 2016 assembly).

Photo sources:

http://static.messynessychic.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/hotos-chamonix.jpg

https://i.pinimg.com/736x/ab/41/c4/ab41c48b0c4fa4c723e12dbf903b5be2.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-Jx5V3fibnV8/VFQqN25jGuI/AAAAAAAAAHk/Rm9_AS9NMJg/s1600/kolb%2Breflective-practice.gif

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

A freezing cold 4am start in the Atlas Mountains sees our tired little group tackle the last 1000 meters or so of Africa’s second highest peak, Mount Toubkal. As pitch black gives way to pink dawn we climb on, and rubble and dust soon become ice and rock. At the 4167-metre-high summit the air is thin, but the view and sense of achievement is as extraordinary as the sky is now rich blue. Looking south standing on a flat rock I am confronted with Africa sprawling hazy to the horizon, so I hold aloft an imaginary Simba and sing ‘The Circle of Life’, loudly. I blame the altitude.

A freezing cold 4am start in the Atlas Mountains sees our tired little group tackle the last 1000 meters or so of Africa’s second highest peak, Mount Toubkal. As pitch black gives way to pink dawn we climb on, and rubble and dust soon become ice and rock. At the 4167-metre-high summit the air is thin, but the view and sense of achievement is as extraordinary as the sky is now rich blue. Looking south standing on a flat rock I am confronted with Africa sprawling hazy to the horizon, so I hold aloft an imaginary Simba and sing ‘The Circle of Life’, loudly. I blame the altitude. For the Romantics, mountains were endlessly fascinating. Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Ruskin et al developed language and ideas which soon became identified as seeking ‘the sublime.’ Perhaps this was by way of a reaction against the nuts and bolts, dirt, detail, grime and grease of the Industrial Revolution. Shelly’s beautiful line ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ certainly gives us a context of vast topographical scale, with the peaks (high above us mere humans beings) themselves dwarfed by the expanse of the heavens. For Shelly, as for the other Romantics, thinking about and visiting mountains allowed for ideas and encounters on an epic scale. Mary Shelley offers us perhaps the most vivid mountains in all romantic literature in her novel Frankenstein. Given the nineteenth-century’s literary love affair with mountain imagery, it is perhaps no surprise that our very own Kitty Ramsey (author of our school song) saw Wimbledon High girls throwing off corsets and crinolines and hiking up those ‘unconquered peaks’ of their own futures. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is full of peaks to climb over, go around or even go through, and, to my mind, even Jay Gatsby climbing the stairs to survey the extravagance of his party below in ‘The Great Gatsby’ or King Kong scaling the needle-like radio mast of the Empire State ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ (Hollywood starlet in hand) shows a (largely male-centric) mountain mythology looming large comfortably into the twentieth century.

For the Romantics, mountains were endlessly fascinating. Byron, Shelley, Wordsworth and Ruskin et al developed language and ideas which soon became identified as seeking ‘the sublime.’ Perhaps this was by way of a reaction against the nuts and bolts, dirt, detail, grime and grease of the Industrial Revolution. Shelly’s beautiful line ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ certainly gives us a context of vast topographical scale, with the peaks (high above us mere humans beings) themselves dwarfed by the expanse of the heavens. For Shelly, as for the other Romantics, thinking about and visiting mountains allowed for ideas and encounters on an epic scale. Mary Shelley offers us perhaps the most vivid mountains in all romantic literature in her novel Frankenstein. Given the nineteenth-century’s literary love affair with mountain imagery, it is perhaps no surprise that our very own Kitty Ramsey (author of our school song) saw Wimbledon High girls throwing off corsets and crinolines and hiking up those ‘unconquered peaks’ of their own futures. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is full of peaks to climb over, go around or even go through, and, to my mind, even Jay Gatsby climbing the stairs to survey the extravagance of his party below in ‘The Great Gatsby’ or King Kong scaling the needle-like radio mast of the Empire State ‘far far above piercing the infinite sky’ (Hollywood starlet in hand) shows a (largely male-centric) mountain mythology looming large comfortably into the twentieth century.

To summarise Schon’s argument; the reflective practitioner in any given task can recognise confusing or unique (positive or negative) events that happen during practice. The ineffective practitioner, says Schon, is confined to repetitive and routine practice, neglecting opportunities to think about what she/he is doing. However, Duckworth’s important point about remaining optimistic and cheerful when we need to be reflective is also worth remembering here. Schon would no doubt have championed Captain Jack Sparrow’s mantra; the problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.

To summarise Schon’s argument; the reflective practitioner in any given task can recognise confusing or unique (positive or negative) events that happen during practice. The ineffective practitioner, says Schon, is confined to repetitive and routine practice, neglecting opportunities to think about what she/he is doing. However, Duckworth’s important point about remaining optimistic and cheerful when we need to be reflective is also worth remembering here. Schon would no doubt have championed Captain Jack Sparrow’s mantra; the problem is not the problem. The problem is your attitude about the problem.

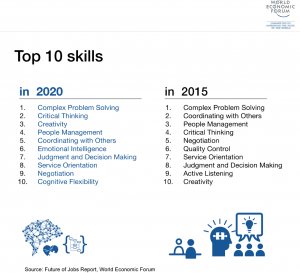

The aim at WHS is to equip students with the new skill set that they will require for the predicted ‘Fourth Industrial revolution 2020’ and to meet the shortage in UK Engineers, especially with women. We needed to change the approach to how Design and Technology is taught in response to a changing world.

The aim at WHS is to equip students with the new skill set that they will require for the predicted ‘Fourth Industrial revolution 2020’ and to meet the shortage in UK Engineers, especially with women. We needed to change the approach to how Design and Technology is taught in response to a changing world.

This was another valuable opportunity where the girls stood and presented their concepts. They responded extremely well to the questions from various delegates who were very impressed with their ideas. After their presentation a number of delegates had further conversations about how the ideas developed and took closer looks at the latest iterations developed in conjunction with DS Smith. A number of delegates were keen to see it progress and one in particular, Sara Nelson RGN from Healthy London Partnership based at the Evelina Hospital at St Thomas, was very interested in running a pilot at her clinic with the textiles monkey bag design created by Sascha. A great day was had by all.

This was another valuable opportunity where the girls stood and presented their concepts. They responded extremely well to the questions from various delegates who were very impressed with their ideas. After their presentation a number of delegates had further conversations about how the ideas developed and took closer looks at the latest iterations developed in conjunction with DS Smith. A number of delegates were keen to see it progress and one in particular, Sara Nelson RGN from Healthy London Partnership based at the Evelina Hospital at St Thomas, was very interested in running a pilot at her clinic with the textiles monkey bag design created by Sascha. A great day was had by all.