Ava (Year 13, Head Girl) explores the Theory of Deconstruction as suggested by Derrida and discusses the confusing nature of both ideas and words.

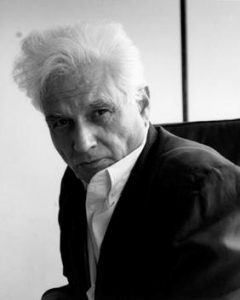

Deconstruction is a theory principally put forward in around the 1970s by a French philosopher named Derrida, who was a man known for his leftist political views and apparently supremely fashionable coats. His theory essentially concerns the dismantling of our excessive loyalty to any particular idea, allowing us to see the aspects of truth that might be buried in its opposite. Derrida believed that all of our thinking was riddled with an unjustified assumption of always privileging one thing over another; critically, this privileging involves a failure to see the full merits and value of the supposedly lesser part of the equation. His thesis can be applied to many age-old questions: take men and women for example; men have systematically been privileged for centuries over women (for no sensible reason) meaning that society has often undervalued or undermined the full value of women.

Deconstruction is a theory principally put forward in around the 1970s by a French philosopher named Derrida, who was a man known for his leftist political views and apparently supremely fashionable coats. His theory essentially concerns the dismantling of our excessive loyalty to any particular idea, allowing us to see the aspects of truth that might be buried in its opposite. Derrida believed that all of our thinking was riddled with an unjustified assumption of always privileging one thing over another; critically, this privileging involves a failure to see the full merits and value of the supposedly lesser part of the equation. His thesis can be applied to many age-old questions: take men and women for example; men have systematically been privileged for centuries over women (for no sensible reason) meaning that society has often undervalued or undermined the full value of women.

Now this might sound like an exceedingly overly simplistic world view, and that Derrida was suggesting a sort of anarchy of language. But Derrida was far subtler than this – he simply wanted to use deconstruction to point out that ideas are always confused and riddled with logical defects and that we must keep their messiness constantly in mind. He wanted to cure humanity of its love of crude simplicity and make us more comfortable with the permanently oscillating nature of wisdom. This is where my new-favourite word comes in: Aporia – a Greek work meaning puzzlement. Derrida thought we should all be more comfortable with a state of Aporia and suggested that refusing to deal with the confusion at the heart of language and life was to avoid grappling with the fraught and kaleidoscopic nature of reality.

This cleanly leads on to another of Derrida’s favourite words: Differánce, a critical outlook concerned with the relationship between text and meaning. The key idea being that you can never actually define a word, but instead you merely defer to other words which in themselves do not have concrete meanings. It all sounds rather airy-fairy and existentialist at this level, but if you break it down it becomes utterly reasonable. Imagine you have no idea what a tree is. Now if I try and explain a tree to you by saying it has branches and roots, this only works if you understand these other words. Thus, I am not truly defining tree, but merely deferring to other words.

Now if those words themselves cannot be truly defined either, and you again have to defer, this uproots (excuse the pun!) the entire belief system at the heart of language. It is in essence a direct attack on Logocentrism, which Derrida understood as an over-hasty, naïve devotion to reason, logic and clear definition, underpinned by a faith in language as the natural and best way to communicate.

Now, Derrida clearly wasn’t unintelligent, and was not of the belief that all hierarchies should be removed, or that we should get rid of language as a whole, but simply that we should be more aware of the irrationality that lies between the lines of language, willingly submit to a more frequent state of “Aporia”, and spend a little more time deconstructing the language and ideas that have made up the world we live in today.