Alex Farrer, one of our Scientists in Residence, looks at ways images can be used both inside and outside the classroom.

The Wellcome Trust is a global charitable foundation that supports scientists and researchers to work on challenges such as the development of Ebola vaccines and training health workers in ways to reduce the risk of infection when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

when working on the front line. What you might not realise about the Wellcome Trust is that they also invest over £5million each year in education research, professional development opportunities and resources and activities for teachers and students. A key part of their science education priority area is primary science and they have a commitment to improving the teaching of science in primary schools through compiling research and evidence for decision making, campaigning for policy change and making recommendations for teachers and governors. Their aim is to transform primary science through increasing teaching time, sharing expertise and high quality resources, and supporting professional development opportunities such as the National STEM Learning Centre.

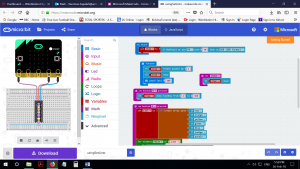

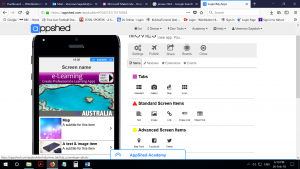

One of the excellent resources that the Wellcome Trust provides is Explorify, a free digital resource, developed with help from teachers and partners such as BBC Learning and the Institution of Engineering and Technology that is “focused on inquiry and curiosity, designed to appeal to children but also ignite or reinvigorate teachers’ passion for science”.

The resource can be found here https://explorify.wellcome.ac.uk

It consists of fun and simple science activities that utilise teaching and learning techniques that give pupils and teachers rich opportunities to question, think, talk and explore STEAM subjects inside and outside the classroom. Confidence and passion is harnessed as links are made and pupils and teachers can see that STEAM knowledge and skills connect us all. They say that a picture is worth a thousand words and Explorify uses images to great effect with videos, photographs and close ups, as well as hands on activities and what if discussion questions.

Explorify is an excellent tool to use in science lessons, especially in primary settings, but many outstanding lessons use different images in a variety of ways to promote talking and thinking in all subject areas, with all age groups. When images are used higher order questioning can be developed and there are also many opportunities to

- use subject specific vocabulary

- explain and justify

- work together

- ask questions

- think about different possible answers

- identify misconceptions

- look for connections

- generate further lesson ideas

- model thinking

- listen to each other

Common examples of questions to ask when using images might include

- odd one outs

- true/falses

- similarities and differences

- sequencing

- what happened next…

All of which involve reflection and asking pupils to justify their answers and persuade others using evidence and examples.

Some less usual examples for you to ponder on include the following:

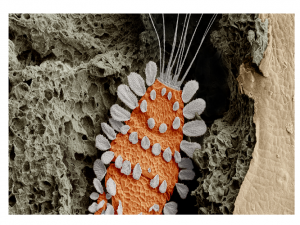

What is this?

Come up with a question that can only be answered yes or no to help work out what it is. Once 8 questions have been answered it is time to decide your answer using the evidence you have gathered. Which question was most useful in finding out the answer?

What is this?

Be specific! Are you sure of your answer? Come up with a 5 convincing bullet points to persuade everyone you are correct. Do you change your mind when you hear the ideas of others?

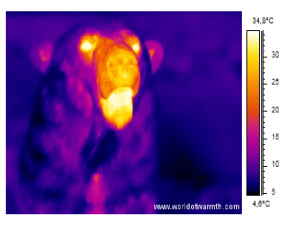

This is the answer:

What is the question? What do you already know about what is happening here?

Scientific words?

Which 5 keys words would you choose inspired by this image? Have you chosen the same words as others have? Where was this photograph taken?

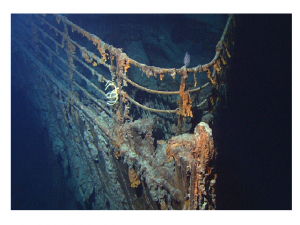

What should the title be for this lesson?

Return at the end of the lesson to your title. Was it the correct title? Do you now need to alter it?

Are polar bears good swimmers?

Are polar bears good enough swimmers for 2018? What time of year was this photograph taken?

As well as in lessons images and questions can be used around the school to promote talking and thinking with all members of the school community.

How many metres per minute does a fly move?

Is it possible to check your estimate?

For more details and examples please see a copy of the presentation entitled Using images to inspire and engage our future scientists that I delivered at the Primary Science Teaching Trust Conference in Belfast.

https://pstt.org.uk/what-we-do/international-primary-science-conference

We are now working on exciting new resource for PSTT utilising images to inspire and engage pupils in conjunction with schools in SW London and with Paul Tyler @glazgow and schools in Scotland. If you have any inspiring images and questions please do send them in!

We look forward to continuing to inspire and engage the scientists of the future as our STEAM journey at Wimbledon High continues.

Follow us on @STEAM_WHS

lp to discover how many parents and pupils you have in your class with scientific interests and skills.

lp to discover how many parents and pupils you have in your class with scientific interests and skills.